Skip over navigation

Article by Jenni Back

Ofsted's 2012 report 'Made to Measure' suggests that although manipulatives are used in some primary schools to support teaching and learning they are not used as effectively or as widely as they might be. This article explores some research into their use and offers some suggestions about how using practical apparatus can support children's mathematical thinking, reasoning and problem solving. Jenni draws on her own experiences of observing the use of manipulatives in Hungarian classrooms and makes links to some rich tasks from the website.

Introduction

I have spent a lot of the last year working with teachers and children on how best to teach arithmetic concepts and procedures to children in primary schools. This has given me a lot of time to consider the ways in which we use apparatus of various kinds to help children to think and to support them to follow, sometimes complex, procedures to arrive at solutions to arithmetic problems. In my own

teaching of children and teachers, my central concern is always on helping them to make sense for themselves of the mathematics we are using and this idea drives all that I do professionally. The central importance of this sense-making process was the core finding of my thesis completed nearly ten years ago now.

So what does the research say about the ways in which practical apparatus and images are used? A recent meta-analysis (Carbonneau, K.J., Marley, S.C. & Selig, J.P. 2013) of studies compared the use of manipulatives, or hands-on practical apparatus in teaching mathematics, with teaching that relied only on abstract mathematical symbols. They found statistically significant evidence that manipulatives had a positive effect on learning with small to moderate effect sizes. Focusing on specific learning outcomes, the study revealed that the effect sizes were moderate to large in the case of retention but small in relation to problem solving, transfer and justification. This is compelling evidence in favour of using manipulatives, based as it was on data collected from 55 studies involving over 7,000 students from Kindergarten to school-leaving age. However, even though this study suggests that using manipulatives is good for mathematical learning, it is the ways in which they are used that are also hugely important.

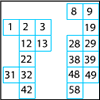

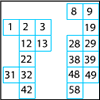

Many teachers that I have worked with over the course of the last year have been confused about what manipulatives to use in specific contexts and I have seen quite a bit of practice where one specific manipulative might appear to teach a given concept and then disappear never to be seen again in the classroom. For

children this can make the practical apparatus rather mystifying and encourage them to think that each manipulative has a specific function in relation to a specific task: we use beads strings to count forward and backwards on a number line but then swap to using a hundred square to count in steps of 10. This might well mean that children become confused about the ways in which each manipulative

reflects aspects of the number system and to see it solely as an adjunct to following a specific procedure. (For an alternative approach to the hundred square that looks at its structure and meaning you could try this task: 100 Square Jigsaw.) This article is written to try to address some of this confusion and to offer research based guidance about the use of

manipulatives in the classroom. As such it will only offer you, as practitioners, a start but I hope it will empower you to examine your own practice and examine the ways in which you use manipulatives with children. I will, as always, be pleased to hear how you get on. My own work depends on receiving this kind of feedback and you can contact me through NRICH.

Many teachers that I have worked with over the course of the last year have been confused about what manipulatives to use in specific contexts and I have seen quite a bit of practice where one specific manipulative might appear to teach a given concept and then disappear never to be seen again in the classroom. For

children this can make the practical apparatus rather mystifying and encourage them to think that each manipulative has a specific function in relation to a specific task: we use beads strings to count forward and backwards on a number line but then swap to using a hundred square to count in steps of 10. This might well mean that children become confused about the ways in which each manipulative

reflects aspects of the number system and to see it solely as an adjunct to following a specific procedure. (For an alternative approach to the hundred square that looks at its structure and meaning you could try this task: 100 Square Jigsaw.) This article is written to try to address some of this confusion and to offer research based guidance about the use of

manipulatives in the classroom. As such it will only offer you, as practitioners, a start but I hope it will empower you to examine your own practice and examine the ways in which you use manipulatives with children. I will, as always, be pleased to hear how you get on. My own work depends on receiving this kind of feedback and you can contact me through NRICH.

What exactly are manipulatives and how are they used?

So what do I mean by manipulatives? I mean all the practical apparatus that we use in our classrooms such as Multilink cubes, Dienes apparatus, counters, place value counters, bead strings, Cuisenaire rods, sticks divided into 10 equal sections and also those that use numerals such as place value cards, hundred squares, digit cards, dice, dominoes and so on. This list is not exhaustive and I am sure you can add your own particular favourites. They are all practical bits of kit that children can pick up and manipulate and which have intrinsic in them various aspects of numbers and the number system that might help children to get to grips with the very abstract notions of numbers, the relationships between them and the ways in which they work in the number system. In preparing to write this article I have been reading a lot of recent research on the subject as well as drawing on my own research in Hungary and England, and this has led me to draw a number of conclusions that I hope will help you in your classrooms.

The history of the use of manipulatives in the classroom goes back over fifty years. A succinct historical summary of this is offered by Patricia Moyer (2001). She comments on Jean Piaget's (1951) work which suggested that children aged seven to ten years old work in primarily concrete ways and

that the abstract notions of mathematics may only be accessible to them through embodiment in practical resources. This was later built on by Zoltan Dienes (1969) who developed his base apparatus, and Caleb Gattegno and Georges Cuisenaire (1954) with their development of Cuisenaire rods. An activity using Cuisenaire rod in similar ways to those Gattegno and Cuisenaire advocate can be found

here: Same Length Trains. Jerome Bruner's (1966) elaboration of enactive, iconic and symbolic modes of working draws further attention to the role of the concrete and representational in progress towards abstract work in symbolic realms. More recent work in the 80s and 90s develops this further using constructivist theories to develop ideas of learning which

see the learner as constructing their own meanings relating concrete manipulatives to the abstract symbols in ways that make sense to them. Moyer (2001) points out that:

The history of the use of manipulatives in the classroom goes back over fifty years. A succinct historical summary of this is offered by Patricia Moyer (2001). She comments on Jean Piaget's (1951) work which suggested that children aged seven to ten years old work in primarily concrete ways and

that the abstract notions of mathematics may only be accessible to them through embodiment in practical resources. This was later built on by Zoltan Dienes (1969) who developed his base apparatus, and Caleb Gattegno and Georges Cuisenaire (1954) with their development of Cuisenaire rods. An activity using Cuisenaire rod in similar ways to those Gattegno and Cuisenaire advocate can be found

here: Same Length Trains. Jerome Bruner's (1966) elaboration of enactive, iconic and symbolic modes of working draws further attention to the role of the concrete and representational in progress towards abstract work in symbolic realms. More recent work in the 80s and 90s develops this further using constructivist theories to develop ideas of learning which

see the learner as constructing their own meanings relating concrete manipulatives to the abstract symbols in ways that make sense to them. Moyer (2001) points out that:

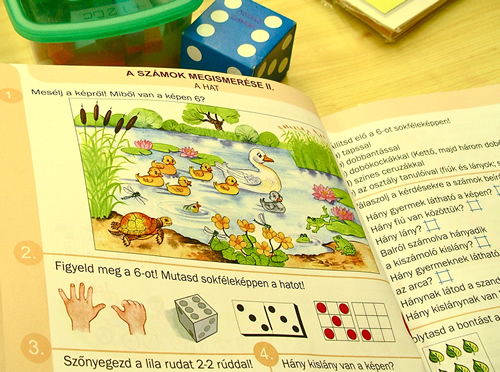

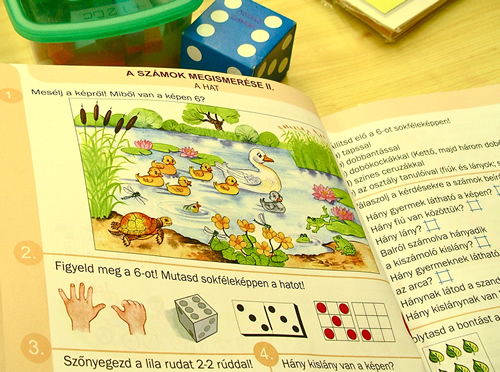

This lesson is described in the article From Objects and Images to Mathematical Ideas. Linked activities focusing on multiple representations can be found here: Matching Numbers and Matching Fractions. My sense from any observations is that Hungarian teachers offer young children this wide range of experiences of specific mathematical concepts in the hope that they will generalise from them and abstract the central mathematical point that is being made.

One of the pieces of research that resonated most strongly with me was reported on by Lio Moscardini (2009) in which he analyses the use of apparatus in teaching subtraction to children with moderate learning difficulties. Although children with special needs are his focus, his analysis and findings are no less relevant to all learners. He makes a valuable distinction between using manipulatives as tools and as crutches. He suggests that manipulatives can be seen as crutches when children use them without understanding to follow a rote leaned procedure to tackle a mathematical task. In this case his research showed that the children's learning was not transferable even to working in the abstract with symbolic representations of the same problem, let alone to tackle a new problem posed in a different scenario. In cases where children were encouraged to make sense of the mathematics by using the manipulatives as tools to solve the problems posed, they were able to transfer their knowledge to novel situations and also to solve problems posed symbolically.

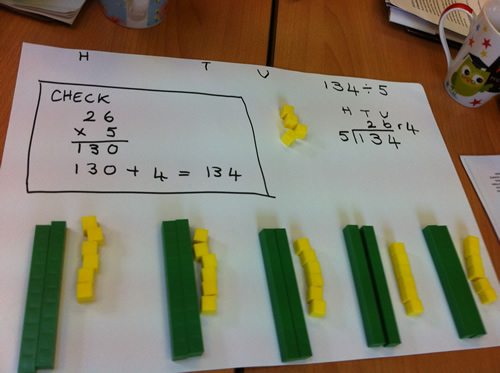

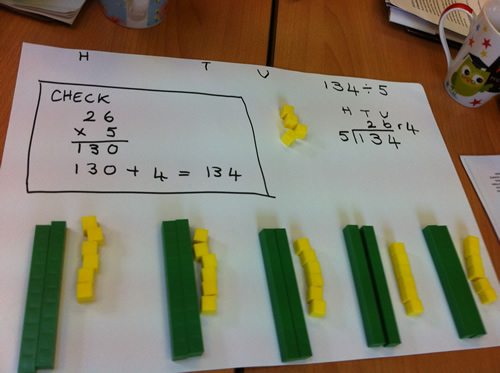

The case studies that Moscardini recounts show some striking examples of manipulatives being used in a range of ways from blindly following a process through to using the manipulatives to demonstrate a result for a fellow pupil. One example that he describes showed one learner explaining to another the solution to the problem of the amount of possession of the ball that one team had in a game of football if the first side had possession for 56 minutes. Using Dienes base apparatus, the learner who was acting as a mentor to a fellow pupil was able to demonstrate that the solution was 34 rather than the answer of 33 that his fellow pupil had got by miscounting a number of marks on his solution. The crucial component here of effective use of the manipulatives seems to be this emphasis on opportunities for children to make sense of the apparatus and to use it to support their own arguments. Manipulatives do have a place as computational tools to support various calculation strategies and demonstrational tools to expound a procedure but it is only when learners themselves use the artefacts to support their own sense making processes that they will begin to see their power as tools for calculation and not just rely on them as crutches to support them in blindly following taught procedures.

My Hungarian research bears this out. Over the course of the last three academic years in which I have been following the progress of the same class and also studying the practice of a Kindergarten (children aged 3 - 6 years old) and Grade 1/2 teacher (children aged 7 -8 years old). On a recent visit I observed a lesson on fractions in which the teacher used representations of fractions with Cuisenaire rods, as fractions of various shapes including rectangles, circles and irregular shapes, as numbers on the number line, as proportions of parallel bars so that comparisons could be made. Once again the manipulatives were being used as an adjunct to generalising: this time about the nature of fractions as numbers.

What does this mean for me in my classroom?

So that is where the research is leading us; the suggestion is that manipulatives can be powerful tools to support sense making, mathematical thinking and reasoning when they are used as tools to support these processes rather than as adjuncts to blindly following a taught procedure to arrive at an answer. The question for us as teachers then is: how can we use this evidence to develop practices in our classrooms that support this? In a context where the core aims of the new curriculum will be the development of pupils' fluency with mathematical procedures as well as the development of ability to solve problems and to reason mathematically, the use of manipulatives as tools has a key role to play. As is common in mathematics education, the research suggests that it is not just what we use that will make a difference to our pupils' learning but how we use it. I have the following suggestions for you for developing your use of manipulatives so that children begin to see them as tools rather than crutches.

Firstly I would open access to all the resources that you have access to and allow the children free reign in choosing what to use to model any problem they may be tackling. I would make sure that children of all ages had this access from 3 to 11 years old and beyond. I would make sure that the range of resources was as wide as possible as different manipulatives have different strengths for different problems and procedures. I know this can be problematic in some contexts and it may be that such a change needs to be made gradually allowing children not to become either overwhelmed by the choice or to engage in 'silly' behaviour relating to the resources but once the culture of the classroom takes this into account it should all settle down into part of your classroom routine. It may also be worthwhile allowing specific lessons for children to examine a particular manipulative and explore its power and potential. This could focus on what the children notice about the resource and how it relates to numbers and the number system.

Secondly I would begin to introduce more opportunities for children to demonstrate to you and one another mathematical truths using a range of artefacts. For instance in considering the calculation 47-28, children could use bead strings, Dienes apparatus, an empty number line, a 100 square, place value counters and collections of objects. By comparing the results which can easily be captured as images on the interactive white board using a webcam, or even short DVD clips, children can examine the structure of the calculation and the usefulness of the manipulatives as tools to solve it. How do the different artefacts support the process of understanding the calculation? The notion of 'Show me' tasks can also become part of the classroom culture.

Thirdly the use of manipulatives can be very powerful in explaining the meaning and justifying the use of different mathematical processes such as the compact algorithms. By asking learners to use manipulatives to demonstrate results and prove their truth in some sense we are developing their mathematical thinking at the deep level required to support their conceptual understanding. In my own work last year I demonstrated how the meaning of the short division algorithm can be unpacked and a number of teachers with whom I shared this said how much it had helped them to understand why something worked that they had never previously fully understood. However it is not in the demonstration that the power lies, it is in having the opportunity to make sense of the process using manipulative resources. Donna Langley wrote about her experience of seeing this and sharing it with her colleagues in an article for Primary Mathematics.

There are of course a whole range of virtual manipulatives available to support the development of children's mathematical learning and many are available on the NRICH website, for example the Cuisenaire Environment. I would commend them to you with the proviso that these virtual resources are one step removed from concrete resources and another step on the way to symbolic representations. I would describe them as iconic in Bruner's terms. So they are no substitute for the real thing but can offer a way of sharing results with whole classes and also for children to demonstrate with on individual computers once they are familiar with the concrete manipulative.

In this article I have concentrated solely on resources to support the learning of arithmetic and ignored those that help with geometric topics but the same arguments would hold and there are similarly effective related interactive resources. That area will have to be the subject of an additional piece of writing. So in conclusion I am suggesting that it is vitally important that in using manipulatives with children we focus on the notion that these tools will only be useful to our learners in their quest to become mathematicians to the extent that we allow them to use the manipulatives to make sense of mathematics and draw their attention to how they do so.

References

Bruner, J. (1960) The Process of Education. Cambridge Massechusetts: Harvard University Press.

Carbonneau, K. J., Marley, S. C. & Selg, S. C. (2013) A meta-analysis of the efficacy of teaching mathematics with concrete manipulatives. Journal of Educational Psychology. Vol 105 (2) pp380-400

Dienes, Z. (1969) Building up mathematics. London: Hutchinson Education

Gattegno, C. & Cuisenaire, G. (1954) Numbers in Colour. London: Heinneman

Langley, D. (2013) Division with Dienes. Primary Mathematics 17(2) p 13 - 15. Leicester: Mathematical Association

Moyer, P. (2001) Are we having fun yet? How teachers use manipulatives to teach mathematics. Educational Studies in Mathematics 47: 175-197. Netherlands: Kluwer.

Moscardini, L. (2009) Tools or Crutches: Apparatus as a sense-making aid in mathematics teaching with children with moderate learning difficulties. Support for Learning. 24(1): 35-41. Oxford: NASEN.

Piaget, J. (1952) The Child's Conception of Number. New York: Humanities Press.

Here is a PDF version of this article.

Or search by topic

Number and algebra

Geometry and measure

Probability and statistics

Working mathematically

Advanced mathematics

For younger learners

Age 5 to 11

Published 2013 Revised 2019

Manipulatives in the Primary Classroom

Ofsted's 2012 report 'Made to Measure' suggests that although manipulatives are used in some primary schools to support teaching and learning they are not used as effectively or as widely as they might be. This article explores some research into their use and offers some suggestions about how using practical apparatus can support children's mathematical thinking, reasoning and problem solving. Jenni draws on her own experiences of observing the use of manipulatives in Hungarian classrooms and makes links to some rich tasks from the website.

Introduction

We have a tendency to adopt different representations and artefacts depending on their suitability for a specific bit of mathematics, often an arithmetic procedure, and in doing so deny the children we teach the opportunities that might be valuable to them to make sense of a particular resource in relation to their own understanding of the concepts involved. The artefact becomes a prop to

support the following of the procedure. It doesn't have to be like that and indeed in other cultures it isn't.

So what does the research say about the ways in which practical apparatus and images are used? A recent meta-analysis (Carbonneau, K.J., Marley, S.C. & Selig, J.P. 2013) of studies compared the use of manipulatives, or hands-on practical apparatus in teaching mathematics, with teaching that relied only on abstract mathematical symbols. They found statistically significant evidence that manipulatives had a positive effect on learning with small to moderate effect sizes. Focusing on specific learning outcomes, the study revealed that the effect sizes were moderate to large in the case of retention but small in relation to problem solving, transfer and justification. This is compelling evidence in favour of using manipulatives, based as it was on data collected from 55 studies involving over 7,000 students from Kindergarten to school-leaving age. However, even though this study suggests that using manipulatives is good for mathematical learning, it is the ways in which they are used that are also hugely important.

Many teachers that I have worked with over the course of the last year have been confused about what manipulatives to use in specific contexts and I have seen quite a bit of practice where one specific manipulative might appear to teach a given concept and then disappear never to be seen again in the classroom. For

children this can make the practical apparatus rather mystifying and encourage them to think that each manipulative has a specific function in relation to a specific task: we use beads strings to count forward and backwards on a number line but then swap to using a hundred square to count in steps of 10. This might well mean that children become confused about the ways in which each manipulative

reflects aspects of the number system and to see it solely as an adjunct to following a specific procedure. (For an alternative approach to the hundred square that looks at its structure and meaning you could try this task: 100 Square Jigsaw.) This article is written to try to address some of this confusion and to offer research based guidance about the use of

manipulatives in the classroom. As such it will only offer you, as practitioners, a start but I hope it will empower you to examine your own practice and examine the ways in which you use manipulatives with children. I will, as always, be pleased to hear how you get on. My own work depends on receiving this kind of feedback and you can contact me through NRICH.

Many teachers that I have worked with over the course of the last year have been confused about what manipulatives to use in specific contexts and I have seen quite a bit of practice where one specific manipulative might appear to teach a given concept and then disappear never to be seen again in the classroom. For

children this can make the practical apparatus rather mystifying and encourage them to think that each manipulative has a specific function in relation to a specific task: we use beads strings to count forward and backwards on a number line but then swap to using a hundred square to count in steps of 10. This might well mean that children become confused about the ways in which each manipulative

reflects aspects of the number system and to see it solely as an adjunct to following a specific procedure. (For an alternative approach to the hundred square that looks at its structure and meaning you could try this task: 100 Square Jigsaw.) This article is written to try to address some of this confusion and to offer research based guidance about the use of

manipulatives in the classroom. As such it will only offer you, as practitioners, a start but I hope it will empower you to examine your own practice and examine the ways in which you use manipulatives with children. I will, as always, be pleased to hear how you get on. My own work depends on receiving this kind of feedback and you can contact me through NRICH.What exactly are manipulatives and how are they used?

So what do I mean by manipulatives? I mean all the practical apparatus that we use in our classrooms such as Multilink cubes, Dienes apparatus, counters, place value counters, bead strings, Cuisenaire rods, sticks divided into 10 equal sections and also those that use numerals such as place value cards, hundred squares, digit cards, dice, dominoes and so on. This list is not exhaustive and I am sure you can add your own particular favourites. They are all practical bits of kit that children can pick up and manipulate and which have intrinsic in them various aspects of numbers and the number system that might help children to get to grips with the very abstract notions of numbers, the relationships between them and the ways in which they work in the number system. In preparing to write this article I have been reading a lot of recent research on the subject as well as drawing on my own research in Hungary and England, and this has led me to draw a number of conclusions that I hope will help you in your classrooms.

The history of the use of manipulatives in the classroom goes back over fifty years. A succinct historical summary of this is offered by Patricia Moyer (2001). She comments on Jean Piaget's (1951) work which suggested that children aged seven to ten years old work in primarily concrete ways and

that the abstract notions of mathematics may only be accessible to them through embodiment in practical resources. This was later built on by Zoltan Dienes (1969) who developed his base apparatus, and Caleb Gattegno and Georges Cuisenaire (1954) with their development of Cuisenaire rods. An activity using Cuisenaire rod in similar ways to those Gattegno and Cuisenaire advocate can be found

here: Same Length Trains. Jerome Bruner's (1966) elaboration of enactive, iconic and symbolic modes of working draws further attention to the role of the concrete and representational in progress towards abstract work in symbolic realms. More recent work in the 80s and 90s develops this further using constructivist theories to develop ideas of learning which

see the learner as constructing their own meanings relating concrete manipulatives to the abstract symbols in ways that make sense to them. Moyer (2001) points out that:

The history of the use of manipulatives in the classroom goes back over fifty years. A succinct historical summary of this is offered by Patricia Moyer (2001). She comments on Jean Piaget's (1951) work which suggested that children aged seven to ten years old work in primarily concrete ways and

that the abstract notions of mathematics may only be accessible to them through embodiment in practical resources. This was later built on by Zoltan Dienes (1969) who developed his base apparatus, and Caleb Gattegno and Georges Cuisenaire (1954) with their development of Cuisenaire rods. An activity using Cuisenaire rod in similar ways to those Gattegno and Cuisenaire advocate can be found

here: Same Length Trains. Jerome Bruner's (1966) elaboration of enactive, iconic and symbolic modes of working draws further attention to the role of the concrete and representational in progress towards abstract work in symbolic realms. More recent work in the 80s and 90s develops this further using constructivist theories to develop ideas of learning which

see the learner as constructing their own meanings relating concrete manipulatives to the abstract symbols in ways that make sense to them. Moyer (2001) points out that:Manipulative materials are objects designed to represent explicitly and concretely mathematical ideas that are abstract. They have both visual and tactile appeal and can be manipulated by learners through hands-on experiences. (p.176)

She goes on to point out that often students use manipulatives to follow a rote learned procedure without a sense of the ways in which the apparatus reflects mathematical structures. Examining how the apparatus reflects and embodies mathematical structure is crucial to using it effectively and to the process of making the meaning of the manipulative transparent to the user. Once again we

come back to the notion of the learner as a sense maker in the classroom and the need to offer learners opportunities to make sense of both the manipulatives used and their relation to the mathematical ideas and problems which they are being used to solve.

Moyer also draws attention to the need for familiarity of the learner with the resource that is being used as a tool so as to reduce the cognitive demand of its use. If a learner is very conscious of various attributes of the resource it is unlikely to facilitate its use as a representation of a specific mathematical structure. I have certainly been aware of this in my own teaching: it takes a lot of play with Cuisenaire rods and familiarity with the proportional relationships between the rods of various colours, before learners can use them to aid the solution of complex calculations such as the addition of fractions. At a more elementary use, the desire to build walls with the little coloured sticks can get in the way of considering which pairs of rods are equivalent to one another from which the number bonds can be derived. In Hungarian classrooms, Kindergarten children are given many opportunities to play freely with the rods before their mathematical structure and relationships are drawn out when they enter formal schooling at the age of rising seven. One resource that I frequently use in work on geometry is loops of string and I find that unless I let learners of any age have a chance to play freely with the string for a while before setting a mathematical task, they will be distracted by their desire to play and explore various properties of the loop of string - usually using it to play 'Cat's Cradle'!

So once learners have access to a range of manipulatives with which they are familiar and which have intrinsic to them particular aspects of mathematical structure, how should we support them to use them? Moyer's study is an important one focusing on actual observations of how teachers use manipulatives and asking them why they use them as they do. All the ten teachers involved were engaged in a programme of study that supplied them with a toolbox of mathematical manipulatives to use in their classrooms and offered them some professional support in doing so.

The teachers involved gave various reasons for using manipulatives. One of these was that using them was more enjoyable than doing mathematics that was solely abstract and symbolic. This was substantiated by the researcher's observations that students were active, engaged and interested in lessons when manipulatives were used. The enjoyment experienced by teachers and learners in using manipulatives meant that teachers tended to use them as a reward for good behaviour rather than solely when they would be a useful adjunct to learning. Some of the teachers used the manipulatives only at the end of the week, the end of the year or when they had time. They didn't seem to view their use as intrinsic to the substance of the core of the curriculum but rather an addition that enhanced enjoyment.

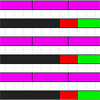

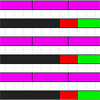

This contrasts dramatically with the use of manipulatives that I have observed in Hungary. There the use of manipulatives is perceived as being central to the early development of mathematical ideas especially for children under the age of eleven. One lesson that I observed was centred on introducing the number six to the children and in it the following manipulatives were used: dominoes, Cuisenaire rods, analogue clock faces, Hungarian number pictures and dominoes. Later in the week coins were used as well. In addition children counted sets of objects, sets of six actions and identified sets of six things from pictures. They showed the finger pattern for six, identified the Roman numerals for six and finally the symbol 6 itself. This concentrated presentation of a variety of representations and manipulatives revealing 'six' enabled the children to generalise about the concept of six across all these different manifestations and, I would suggest, to abstract a deeper notion of the qualities of six. They made walls of Cuisenaire rods the same length as the six rod and collections of dominoes with six spots on them and so gave themselves a concrete experience of the ways in which six can be partitioned in two sets.

Moyer also draws attention to the need for familiarity of the learner with the resource that is being used as a tool so as to reduce the cognitive demand of its use. If a learner is very conscious of various attributes of the resource it is unlikely to facilitate its use as a representation of a specific mathematical structure. I have certainly been aware of this in my own teaching: it takes a lot of play with Cuisenaire rods and familiarity with the proportional relationships between the rods of various colours, before learners can use them to aid the solution of complex calculations such as the addition of fractions. At a more elementary use, the desire to build walls with the little coloured sticks can get in the way of considering which pairs of rods are equivalent to one another from which the number bonds can be derived. In Hungarian classrooms, Kindergarten children are given many opportunities to play freely with the rods before their mathematical structure and relationships are drawn out when they enter formal schooling at the age of rising seven. One resource that I frequently use in work on geometry is loops of string and I find that unless I let learners of any age have a chance to play freely with the string for a while before setting a mathematical task, they will be distracted by their desire to play and explore various properties of the loop of string - usually using it to play 'Cat's Cradle'!

So once learners have access to a range of manipulatives with which they are familiar and which have intrinsic to them particular aspects of mathematical structure, how should we support them to use them? Moyer's study is an important one focusing on actual observations of how teachers use manipulatives and asking them why they use them as they do. All the ten teachers involved were engaged in a programme of study that supplied them with a toolbox of mathematical manipulatives to use in their classrooms and offered them some professional support in doing so.

The teachers involved gave various reasons for using manipulatives. One of these was that using them was more enjoyable than doing mathematics that was solely abstract and symbolic. This was substantiated by the researcher's observations that students were active, engaged and interested in lessons when manipulatives were used. The enjoyment experienced by teachers and learners in using manipulatives meant that teachers tended to use them as a reward for good behaviour rather than solely when they would be a useful adjunct to learning. Some of the teachers used the manipulatives only at the end of the week, the end of the year or when they had time. They didn't seem to view their use as intrinsic to the substance of the core of the curriculum but rather an addition that enhanced enjoyment.

This contrasts dramatically with the use of manipulatives that I have observed in Hungary. There the use of manipulatives is perceived as being central to the early development of mathematical ideas especially for children under the age of eleven. One lesson that I observed was centred on introducing the number six to the children and in it the following manipulatives were used: dominoes, Cuisenaire rods, analogue clock faces, Hungarian number pictures and dominoes. Later in the week coins were used as well. In addition children counted sets of objects, sets of six actions and identified sets of six things from pictures. They showed the finger pattern for six, identified the Roman numerals for six and finally the symbol 6 itself. This concentrated presentation of a variety of representations and manipulatives revealing 'six' enabled the children to generalise about the concept of six across all these different manifestations and, I would suggest, to abstract a deeper notion of the qualities of six. They made walls of Cuisenaire rods the same length as the six rod and collections of dominoes with six spots on them and so gave themselves a concrete experience of the ways in which six can be partitioned in two sets.

This lesson is described in the article From Objects and Images to Mathematical Ideas. Linked activities focusing on multiple representations can be found here: Matching Numbers and Matching Fractions. My sense from any observations is that Hungarian teachers offer young children this wide range of experiences of specific mathematical concepts in the hope that they will generalise from them and abstract the central mathematical point that is being made.

One of the pieces of research that resonated most strongly with me was reported on by Lio Moscardini (2009) in which he analyses the use of apparatus in teaching subtraction to children with moderate learning difficulties. Although children with special needs are his focus, his analysis and findings are no less relevant to all learners. He makes a valuable distinction between using manipulatives as tools and as crutches. He suggests that manipulatives can be seen as crutches when children use them without understanding to follow a rote leaned procedure to tackle a mathematical task. In this case his research showed that the children's learning was not transferable even to working in the abstract with symbolic representations of the same problem, let alone to tackle a new problem posed in a different scenario. In cases where children were encouraged to make sense of the mathematics by using the manipulatives as tools to solve the problems posed, they were able to transfer their knowledge to novel situations and also to solve problems posed symbolically.

The case studies that Moscardini recounts show some striking examples of manipulatives being used in a range of ways from blindly following a process through to using the manipulatives to demonstrate a result for a fellow pupil. One example that he describes showed one learner explaining to another the solution to the problem of the amount of possession of the ball that one team had in a game of football if the first side had possession for 56 minutes. Using Dienes base apparatus, the learner who was acting as a mentor to a fellow pupil was able to demonstrate that the solution was 34 rather than the answer of 33 that his fellow pupil had got by miscounting a number of marks on his solution. The crucial component here of effective use of the manipulatives seems to be this emphasis on opportunities for children to make sense of the apparatus and to use it to support their own arguments. Manipulatives do have a place as computational tools to support various calculation strategies and demonstrational tools to expound a procedure but it is only when learners themselves use the artefacts to support their own sense making processes that they will begin to see their power as tools for calculation and not just rely on them as crutches to support them in blindly following taught procedures.

My Hungarian research bears this out. Over the course of the last three academic years in which I have been following the progress of the same class and also studying the practice of a Kindergarten (children aged 3 - 6 years old) and Grade 1/2 teacher (children aged 7 -8 years old). On a recent visit I observed a lesson on fractions in which the teacher used representations of fractions with Cuisenaire rods, as fractions of various shapes including rectangles, circles and irregular shapes, as numbers on the number line, as proportions of parallel bars so that comparisons could be made. Once again the manipulatives were being used as an adjunct to generalising: this time about the nature of fractions as numbers.

What does this mean for me in my classroom?

So that is where the research is leading us; the suggestion is that manipulatives can be powerful tools to support sense making, mathematical thinking and reasoning when they are used as tools to support these processes rather than as adjuncts to blindly following a taught procedure to arrive at an answer. The question for us as teachers then is: how can we use this evidence to develop practices in our classrooms that support this? In a context where the core aims of the new curriculum will be the development of pupils' fluency with mathematical procedures as well as the development of ability to solve problems and to reason mathematically, the use of manipulatives as tools has a key role to play. As is common in mathematics education, the research suggests that it is not just what we use that will make a difference to our pupils' learning but how we use it. I have the following suggestions for you for developing your use of manipulatives so that children begin to see them as tools rather than crutches.

Firstly I would open access to all the resources that you have access to and allow the children free reign in choosing what to use to model any problem they may be tackling. I would make sure that children of all ages had this access from 3 to 11 years old and beyond. I would make sure that the range of resources was as wide as possible as different manipulatives have different strengths for different problems and procedures. I know this can be problematic in some contexts and it may be that such a change needs to be made gradually allowing children not to become either overwhelmed by the choice or to engage in 'silly' behaviour relating to the resources but once the culture of the classroom takes this into account it should all settle down into part of your classroom routine. It may also be worthwhile allowing specific lessons for children to examine a particular manipulative and explore its power and potential. This could focus on what the children notice about the resource and how it relates to numbers and the number system.

Secondly I would begin to introduce more opportunities for children to demonstrate to you and one another mathematical truths using a range of artefacts. For instance in considering the calculation 47-28, children could use bead strings, Dienes apparatus, an empty number line, a 100 square, place value counters and collections of objects. By comparing the results which can easily be captured as images on the interactive white board using a webcam, or even short DVD clips, children can examine the structure of the calculation and the usefulness of the manipulatives as tools to solve it. How do the different artefacts support the process of understanding the calculation? The notion of 'Show me' tasks can also become part of the classroom culture.

Thirdly the use of manipulatives can be very powerful in explaining the meaning and justifying the use of different mathematical processes such as the compact algorithms. By asking learners to use manipulatives to demonstrate results and prove their truth in some sense we are developing their mathematical thinking at the deep level required to support their conceptual understanding. In my own work last year I demonstrated how the meaning of the short division algorithm can be unpacked and a number of teachers with whom I shared this said how much it had helped them to understand why something worked that they had never previously fully understood. However it is not in the demonstration that the power lies, it is in having the opportunity to make sense of the process using manipulative resources. Donna Langley wrote about her experience of seeing this and sharing it with her colleagues in an article for Primary Mathematics.

There are of course a whole range of virtual manipulatives available to support the development of children's mathematical learning and many are available on the NRICH website, for example the Cuisenaire Environment. I would commend them to you with the proviso that these virtual resources are one step removed from concrete resources and another step on the way to symbolic representations. I would describe them as iconic in Bruner's terms. So they are no substitute for the real thing but can offer a way of sharing results with whole classes and also for children to demonstrate with on individual computers once they are familiar with the concrete manipulative.

In this article I have concentrated solely on resources to support the learning of arithmetic and ignored those that help with geometric topics but the same arguments would hold and there are similarly effective related interactive resources. That area will have to be the subject of an additional piece of writing. So in conclusion I am suggesting that it is vitally important that in using manipulatives with children we focus on the notion that these tools will only be useful to our learners in their quest to become mathematicians to the extent that we allow them to use the manipulatives to make sense of mathematics and draw their attention to how they do so.

References

Bruner, J. (1960) The Process of Education. Cambridge Massechusetts: Harvard University Press.

Carbonneau, K. J., Marley, S. C. & Selg, S. C. (2013) A meta-analysis of the efficacy of teaching mathematics with concrete manipulatives. Journal of Educational Psychology. Vol 105 (2) pp380-400

Dienes, Z. (1969) Building up mathematics. London: Hutchinson Education

Gattegno, C. & Cuisenaire, G. (1954) Numbers in Colour. London: Heinneman

Langley, D. (2013) Division with Dienes. Primary Mathematics 17(2) p 13 - 15. Leicester: Mathematical Association

Moyer, P. (2001) Are we having fun yet? How teachers use manipulatives to teach mathematics. Educational Studies in Mathematics 47: 175-197. Netherlands: Kluwer.

Moscardini, L. (2009) Tools or Crutches: Apparatus as a sense-making aid in mathematics teaching with children with moderate learning difficulties. Support for Learning. 24(1): 35-41. Oxford: NASEN.

Piaget, J. (1952) The Child's Conception of Number. New York: Humanities Press.

Here is a PDF version of this article.