Or search by topic

Number and algebra

Geometry and measure

Probability and statistics

Working mathematically

Advanced mathematics

For younger learners

An Appearing Act

- Problem

- Student Solutions

- Teachers' Resources

The nrich group from Deansbrook Junior School found an explanation for the change.

You use the same amount of paper each time so there is no real change in area. When you create the new rectangle, to the naked eye, it appears to fit together correctly. However, it doesnt fit as there is the slighest gap between the diagonals of the shape and the dots don't fit together in perfectly straight lines.

Matthew from St Anthony's Catholic College, Australia looked at the gradients of the triangles to try to explain the illusion.

It is clear once you start looking at the gradients of the edges of the shapes after cutting.

If the pieces of paper were to fit together the gradients of the edges of the papers touching together would have to be the same.

However, if you measure the gradient of the sloping side of one of the trapezia at the top, it has a gradient of $\frac{2}{5}$.

The the gradient of the hypotenuses of the lower triangles is $\frac{3}{8}$

Now if you compare the gradients, we have $\frac{2}{5}$ and $\frac{3}{8}$.These are not the same, so the shapes don't fit.

The trick in this problem is that $\frac{2}{5}$ and $\frac{3}{8}$ are actually very similar gradients (this is easier seen in decimal, $0.4$ and $0.375$). Similar enough to look like they are the same

when positioned roughly together, so you don't see the gaps.

The reason this works is because the gaps between the shapes are small enough you don't notice them. This trick can be repeated, you just need to make sure that the shapes you cut up have similar enough gradients that the viewer won't spot the gaps.

Zach sent us this excellent solution, which looks at the family of squares and rectangles examined in this problem. Excellent work, Zach!

The first thing that springs to mind is that $5$, $8$ and $13$ are consecutive Fibonacci numbers. I wondered if the pattern could be repeated on a larger and/or smaller scale. Looking at the Fibonacci sequence, we have:

$1$

$1$

$2$

$3$

$5$

$8$

$13$

$21$

$34$

$55$

$89$

$144$

$233$

$377$...

Looking at the original set {$5$, $8$, $13$}, we have that the area of the square is $8^2 = 64$ and the area of the rectangle is $5\times 13 = 65$. Here the rectangle is bigger.

Trying this with another set, say {$55$, $89$, $144$}, we have that the area of the square is $89^2 = 7921$ and the area of the rectangle is $55\times 144 = 7290$. This time the rectangle is smaller than the square, but the difference is still equal to $1$.

I decided to try out some other "triplets", to see if I could find a pattern. My process was to: take 3 consecutive Fibonacci numbers, square the middle number and multiply the first and third. This is what I found:

| Fibonacci set | Square the middle number | Multiply the first and third numbers | Which is bigger? | Observations | |

| Square | Rectangle | ||||

| {$1$, $1$, $2$} | $1^2 = 1$ | $1\times 2 = 2$ | $\checkmark$ | This is the smallest set. | |

| {$1$, $2$, $3$} | $2^2 = 4$ | $1\times 3 = 3$ | $\checkmark$ | There is a constant difference of one. This alternates between the square and the rectangle (starting with the rectangle as the biggest). | |

| {$2$, $3$, $5$} | $3^2 = 9$ | $2\times 5 = 10$ | $\checkmark$ | ||

| {$3$, $5$, $8$} | $5^2 = 25$ | $3\times 8 = 24$ | $\checkmark$ | ||

| {$5$, $8$, $13$} | $8^2 = 64$ | $5\times 13 = 65$ | $\checkmark$ | ||

| {$8$, $13$, $21$} | $13^2 = 169$ | $8\times 21 = 168$ | $\checkmark$ | ||

| {$13$, $21$, $34$} | $21^2 = 441$ | $13\times 34 = 442$ | $\checkmark$ | ||

| {$21$, $34$, $55$} | $34^2 = 1156$ | $21\times 55 = 1155$ | $\checkmark$ | ||

| {$34$, $55$, $89$} | $55^2 = 3025$ | $34\times 89 = 3026$ | $\checkmark$ | ||

| {$55$, $89$, $144$} | $89^2 = 7921$ | $55\times 144 = 7920$ | $\checkmark$ | ||

If the rectangle is bigger, there will be a gap of $1$ unit$^2$, but if the square is bigger then there will be an overlap of $1$ unit$^2$ in its associated rectangle.

I also thought I should try some bigger numbers, just to check:

| Square | Rectangle | |||

| {$1597$, $2584$, $4181$} | $2584^2 = 6677056$ | $1597\times 4181 = 6677057$ | $\checkmark$ | |

| {$2584$, $4181$, $6765$} | $4181^2 = 17480761$ | $2584\times 6765= 17480760$ | $\checkmark$ |

I did go on and try even bigger numbers, and the pattern continued to hold.

This seems to be an interesting feature of Fibonacci numbers, but it's only because I noticed the sequence that I was able to explore this relationship!

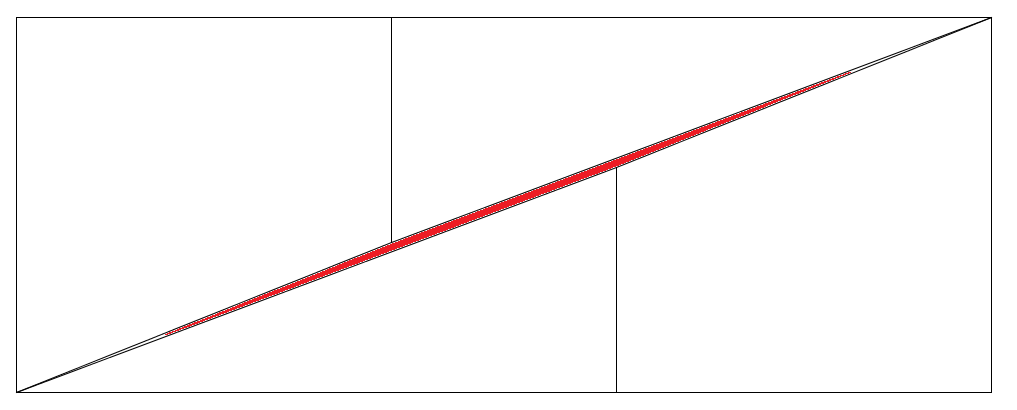

Throughout this pattern, there is always a constant overlap or gap of $1$ unit$^2$. The smaller the set, the more obvious this overlap or gap becomes. The larger the numbers get, the harder it is to see with the naked eye. To illustrate this, here are some pictures of the smaller sets:

{$1$, $1$, $2$}

{$1$, $2$, $3$}

{$2$, $3$, $5$}

{$3$, $5$, $8$}

Here we can see that the difference in area is really obvious for the smallest sets. But it becomes harder to see as the sets get bigger. This is because that difference of 1 unit$^2$ gets spread out over a longer diagonal each time, so the 1 unit$^2$ gets spread out over a larger area each time, so it becomes less noticeable.

I love Fibonacci numbers!

You may also like

Pair Sums

Five numbers added together in pairs produce: 0, 2, 4, 4, 6, 8, 9, 11, 13, 15 What are the five numbers?

Summing Consecutive Numbers

15 = 7 + 8 and 10 = 1 + 2 + 3 + 4. Can you say which numbers can be expressed as the sum of two or more consecutive integers?

Big Powers

Three people chose this as a favourite problem. It is the sort of problem that needs thinking time - but once the connection is made it gives access to many similar ideas.