Skip over navigation

Or search by topic

Number and algebra

Geometry and measure

Probability and statistics

Working mathematically

Advanced mathematics

For younger learners

A Tangent Is ...

Age 16 to 18

Challenge Level

- Problem

- Student Solutions

Mateusz from Ashcroft Technology Academy, Joseph from Ermysted's Grammar School, Louis from EMS submitted solutions to this problem. Thank you!

The first definition of a tangent was "A tangent is a straight line which only meets the curve at that

one point.".

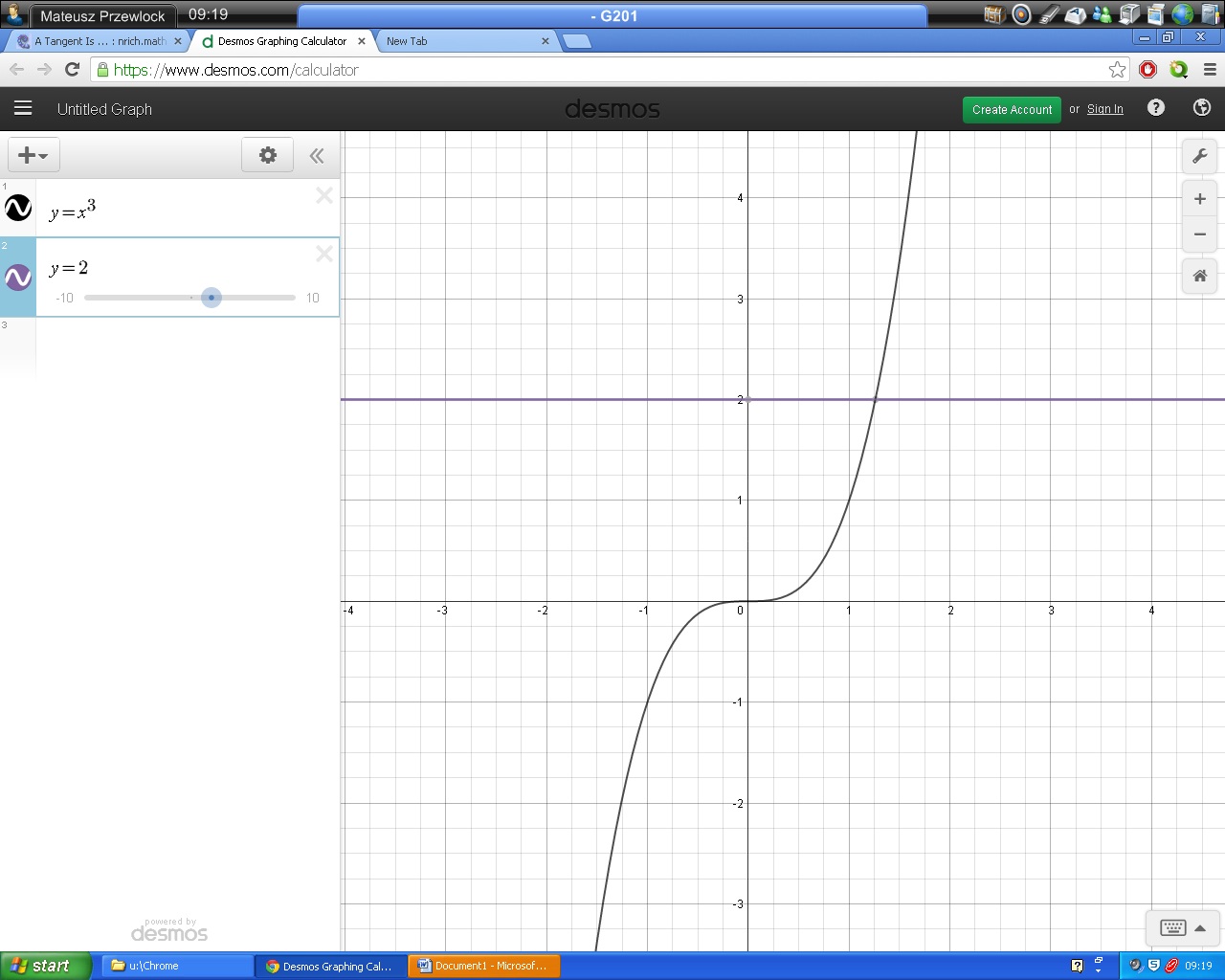

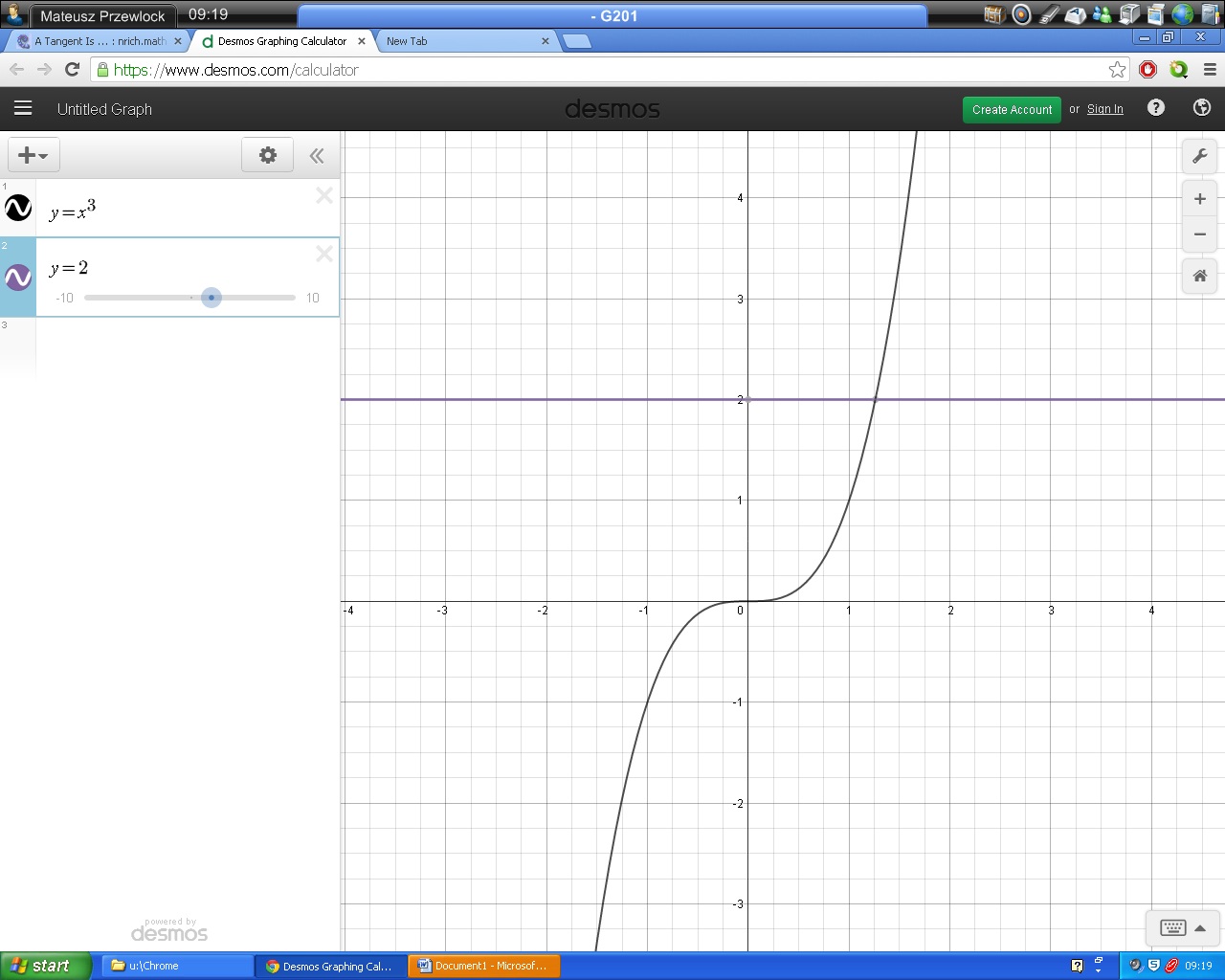

Here is Mateusz's counter-example:

This is, by definition, “a straight line which only meets the curve at that one point.” However, this is not a tangent, because it does not have the same gradient as the curve at that point which is found by integrating the function (in this case, the gradient is $3x^2$).

Here is Joseph's counter-example:

Consider the tangent to $y=cos(x)$ when $x=0$, that is $y=1$. Not only does it meet

and touch the curve more than once, it touches it an infinite number of

times.

Here is Louis' counter-example:

Curves with two or more stationary points can be used as a

counterexample. An example of one of these is the cubic $y = x^3-3x+3$. The

line $y=5$ is a tangent at the local maximum at $(-1,5)$, yet it also crosses

the line at $(2,5)$. This means that it meets the curve at two points, yet is

a tangent.

The second definition of a tangent was "A tangent is a straight line which touches the curve at that point only."

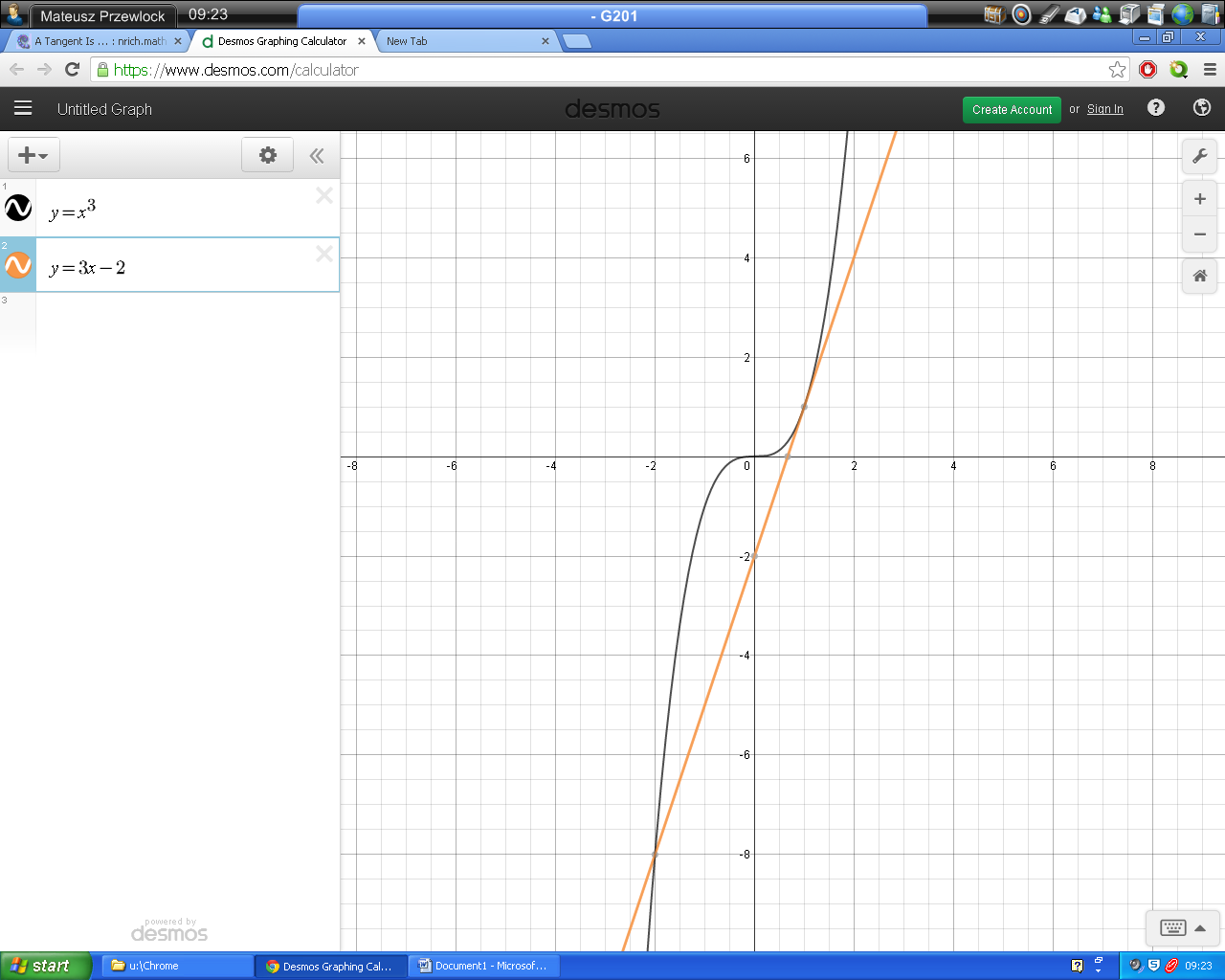

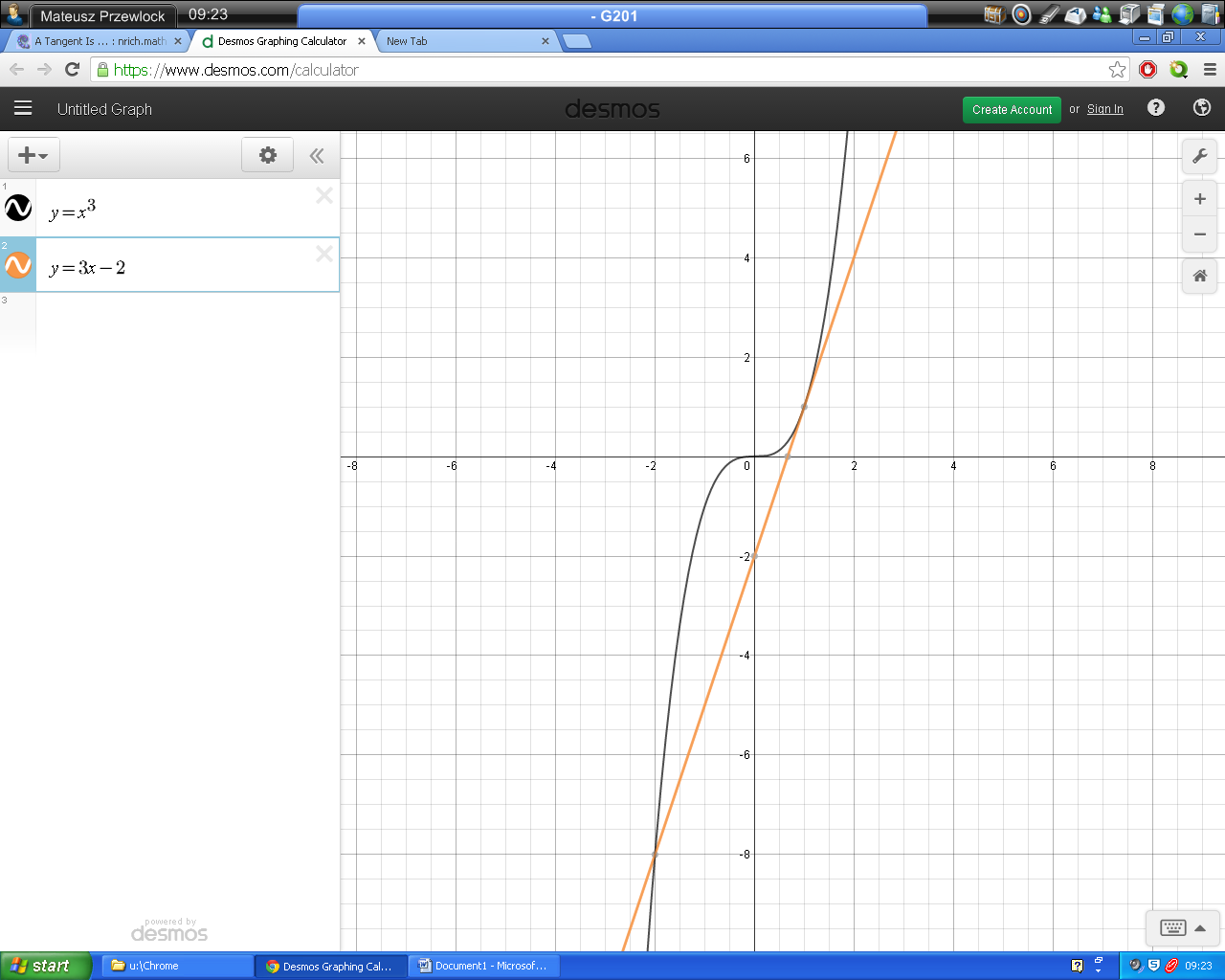

Here is Mateusz's counter-example:

This is an example to disprove the definition “A tangent is a straight line which touches the curve at that point only.” The line y=3x-2 touches the curve and has the same gradient as the function at that point, however it intersects the curve at more than one point. Therefore, the second definition is not necessarily true.

Joseph used the same counter-example as for the first definition of a tangent: $y=1$ and $y=cos(x)$.

Louis also used the same counter-example as for the first definition of a tangent: $y = x^3-3x+3$ and $y=5$

The third definition of a tangent was "A tangent is a straight line which meets the curve at that point, but the curve is all on one side of the line."

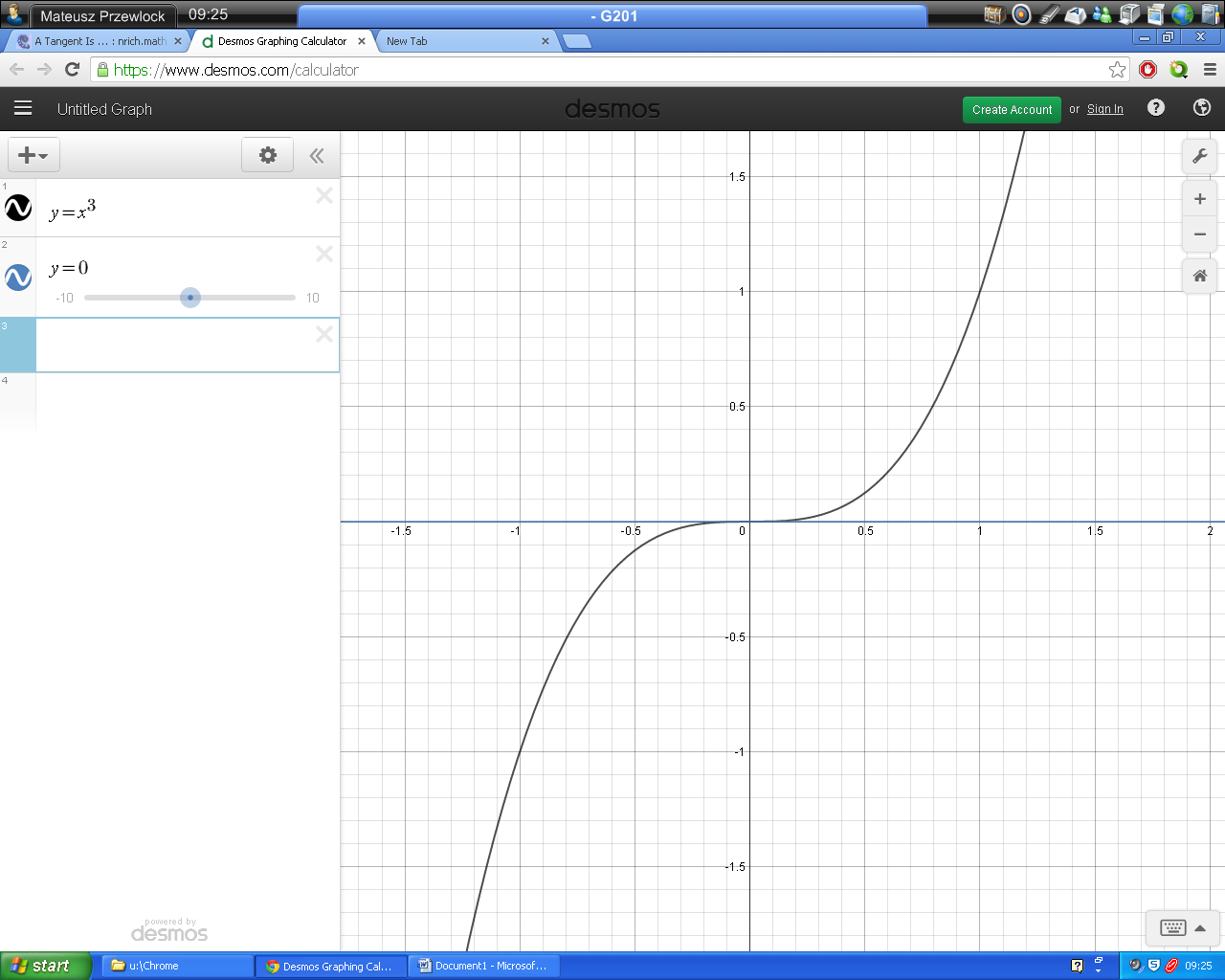

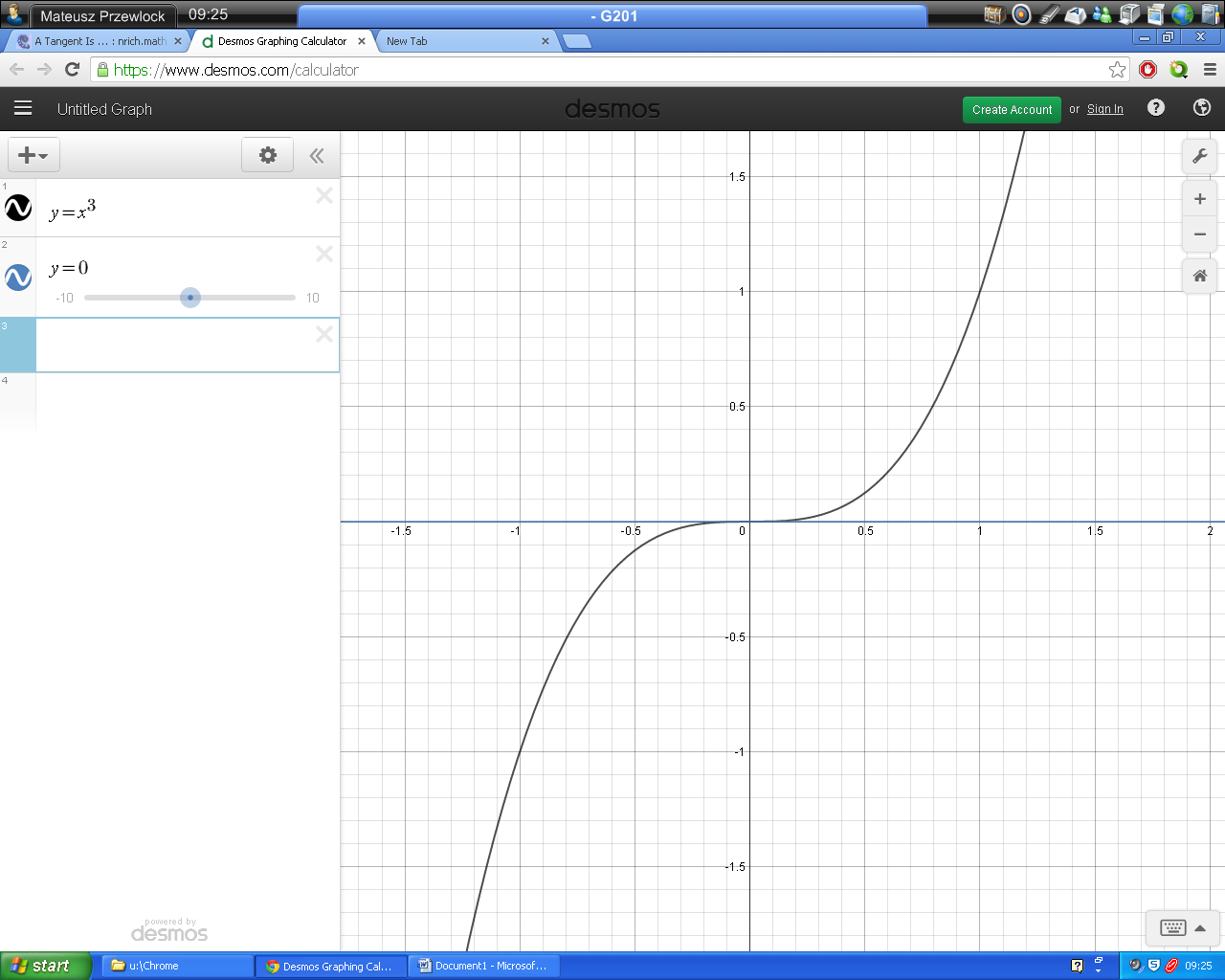

Here is Mateusz's and Joseph's counter-example:

Louis used the same counter-example as for the first definition of a tangent: $y = x^3-3x+3$ and $y=5$.

The fourth definition of a tangent was "A tangent is a straight line which meets the curve at that point, but near that point, the curve is all on one side of the line."

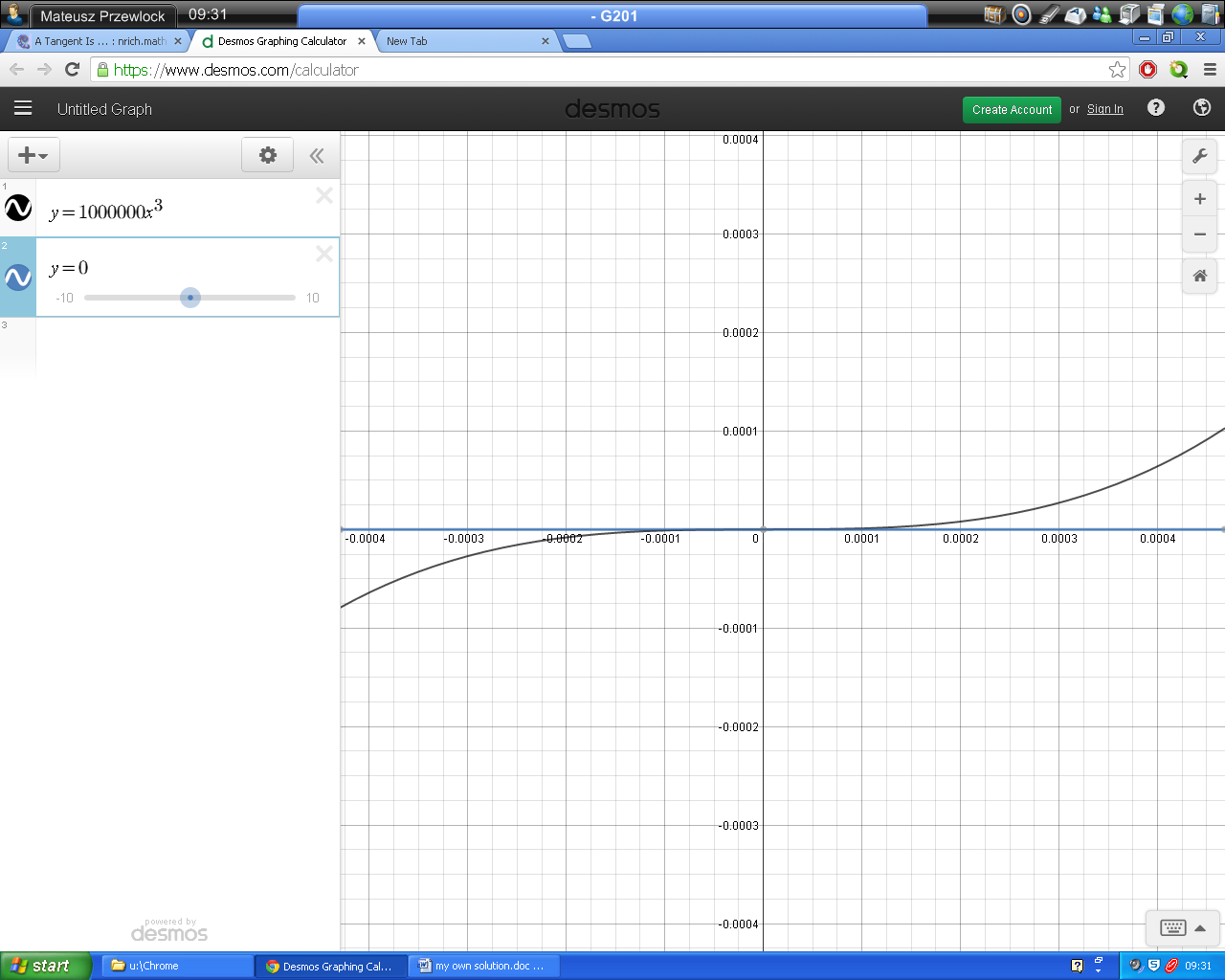

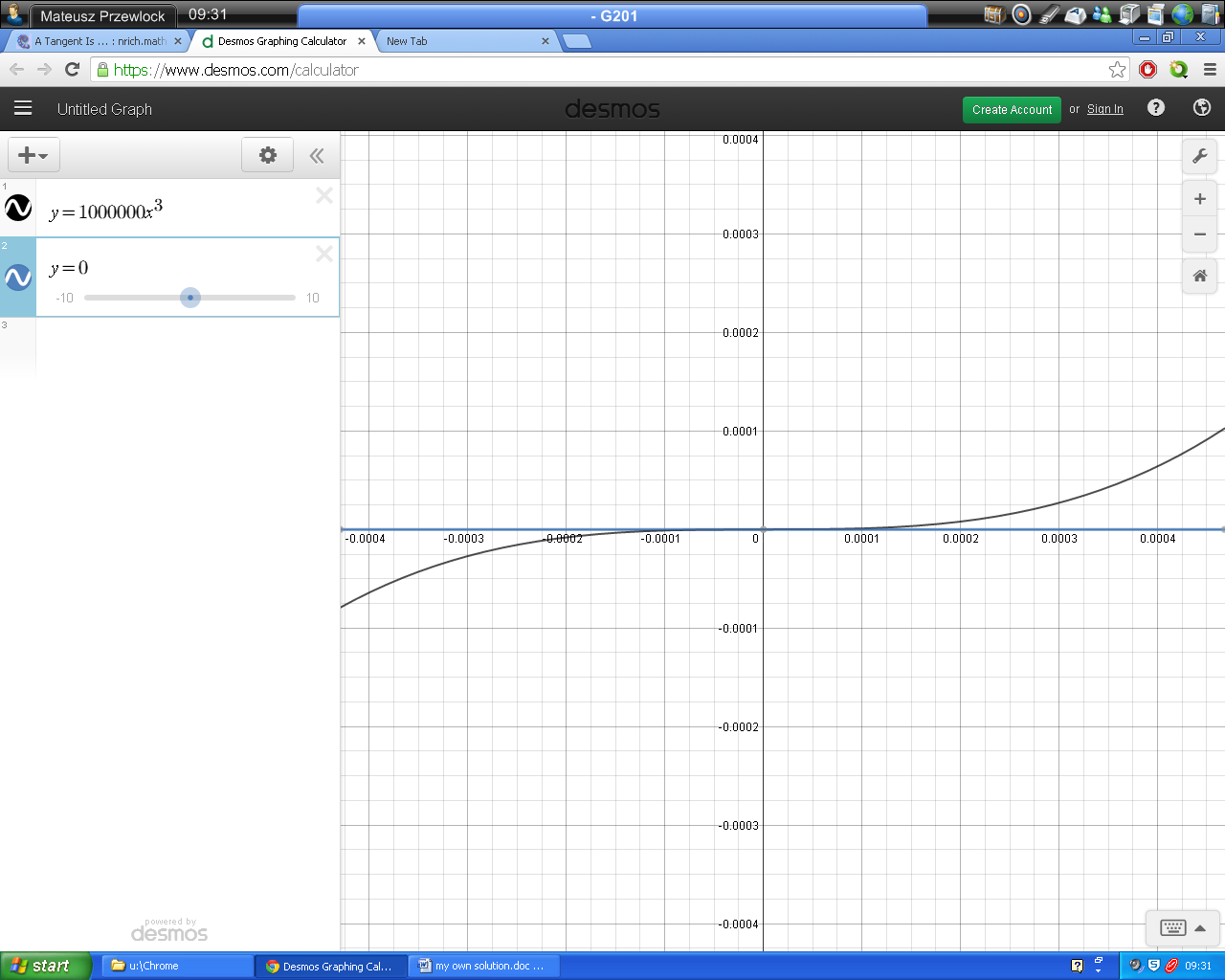

Mateusz and Joseph again used the example of $x^3$ and $x=0$:

This case shows that, even for very large functions with only very small changes in x, a tangent can still meet the curve only at one point with the function being on both sides of the tangent. This means that, even “near that point”, the curve doesn't necessarily have to be on only one side of the function.

Here is Louis' counter-example:

This depends on your definition of 'near'. For example, the curve $y = x^3-x$

has a local maximum (with which a horizontal tangent can be drawn to) and

another point with the same y-coordinate (which the tangent will go

through, making the line on the other side of the curve) with a difference

in $x$-coordinate by less than $2$. However, for the curve $y = x^3-0.001x$, which

is similar but with a different coefficient for the $x$ term, these two

points are within $0.06$ of each other, which is definitely 'near'.

Mateusz's definition of a tangent:

A more accurate definition for a tangent would be “a straight line with the same gradient as the function at the point at which it is drawn, which does not intersect the curve at the point at which it is drawn.” This doesn't exclude the possibility that the tangent could very well bisect the curve into two sides, and it also includes a key feature of a tangent, which is that it has the same gradient as the curve at the point where the tangent is drawn. It also takes into account the fact that the gradient could intersect the curve at more than one point, as tangents are intended to only touch the curve at a specific point, but not intersect the curve at that specific point.

Joseph's definition of a tangent:

For a tangent to a curve $y=f(x)$ for a given value of $x$: a straight line $y=g(x)$ such that $f(x)=g(x)$ and $f'(x)=g'(x)$ for that given value of $x$.

Louis' definition of a tangent:

A good definition would be something similar to: "A tangent is a

straight line which passes through the same point as the curve, and at this

point has a gradient perpendicular to that of the curve."

The first definition of a tangent was "A tangent is a straight line which only meets the curve at that

one point.".

Here is Mateusz's counter-example:

This is, by definition, “a straight line which only meets the curve at that one point.” However, this is not a tangent, because it does not have the same gradient as the curve at that point which is found by integrating the function (in this case, the gradient is $3x^2$).

Here is Joseph's counter-example:

Consider the tangent to $y=cos(x)$ when $x=0$, that is $y=1$. Not only does it meet

and touch the curve more than once, it touches it an infinite number of

times.

Here is Louis' counter-example:

Curves with two or more stationary points can be used as a

counterexample. An example of one of these is the cubic $y = x^3-3x+3$. The

line $y=5$ is a tangent at the local maximum at $(-1,5)$, yet it also crosses

the line at $(2,5)$. This means that it meets the curve at two points, yet is

a tangent.

The second definition of a tangent was "A tangent is a straight line which touches the curve at that point only."

Here is Mateusz's counter-example:

This is an example to disprove the definition “A tangent is a straight line which touches the curve at that point only.” The line y=3x-2 touches the curve and has the same gradient as the function at that point, however it intersects the curve at more than one point. Therefore, the second definition is not necessarily true.

Joseph used the same counter-example as for the first definition of a tangent: $y=1$ and $y=cos(x)$.

Louis also used the same counter-example as for the first definition of a tangent: $y = x^3-3x+3$ and $y=5$

The third definition of a tangent was "A tangent is a straight line which meets the curve at that point, but the curve is all on one side of the line."

Here is Mateusz's and Joseph's counter-example:

Louis used the same counter-example as for the first definition of a tangent: $y = x^3-3x+3$ and $y=5$.

The fourth definition of a tangent was "A tangent is a straight line which meets the curve at that point, but near that point, the curve is all on one side of the line."

Mateusz and Joseph again used the example of $x^3$ and $x=0$:

This case shows that, even for very large functions with only very small changes in x, a tangent can still meet the curve only at one point with the function being on both sides of the tangent. This means that, even “near that point”, the curve doesn't necessarily have to be on only one side of the function.

Here is Louis' counter-example:

This depends on your definition of 'near'. For example, the curve $y = x^3-x$

has a local maximum (with which a horizontal tangent can be drawn to) and

another point with the same y-coordinate (which the tangent will go

through, making the line on the other side of the curve) with a difference

in $x$-coordinate by less than $2$. However, for the curve $y = x^3-0.001x$, which

is similar but with a different coefficient for the $x$ term, these two

points are within $0.06$ of each other, which is definitely 'near'.

Mateusz's definition of a tangent:

A more accurate definition for a tangent would be “a straight line with the same gradient as the function at the point at which it is drawn, which does not intersect the curve at the point at which it is drawn.” This doesn't exclude the possibility that the tangent could very well bisect the curve into two sides, and it also includes a key feature of a tangent, which is that it has the same gradient as the curve at the point where the tangent is drawn. It also takes into account the fact that the gradient could intersect the curve at more than one point, as tangents are intended to only touch the curve at a specific point, but not intersect the curve at that specific point.

Joseph's definition of a tangent:

For a tangent to a curve $y=f(x)$ for a given value of $x$: a straight line $y=g(x)$ such that $f(x)=g(x)$ and $f'(x)=g'(x)$ for that given value of $x$.

Louis' definition of a tangent:

A good definition would be something similar to: "A tangent is a

straight line which passes through the same point as the curve, and at this

point has a gradient perpendicular to that of the curve."

You may also like

Powerful Quadratics

This comes in two parts, with the first being less fiendish than the second. It’s great for practising both quadratics and laws of indices, and you can get a lot from making sure that you find all the solutions. For a real challenge (requiring a bit more knowledge), you could consider finding the complex solutions.

Discriminating

You're invited to decide whether statements about the number of solutions of a quadratic equation are always, sometimes or never true.

Factorisable Quadratics

This will encourage you to think about whether all quadratics can be factorised and to develop a better understanding of the effect that changing the coefficients has on the factorised form.