Skip over navigation

Or search by topic

Number and algebra

Geometry and measure

Probability and statistics

Working mathematically

Advanced mathematics

For younger learners

Quadrature of the Lunes

Age 16 to 18

Challenge Level

- Problem

- Student Solutions

Michael, from Exeter Mathematics School, explained how to do question 1.

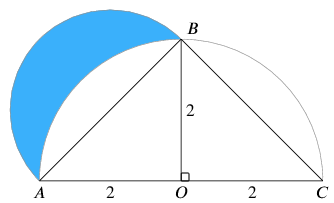

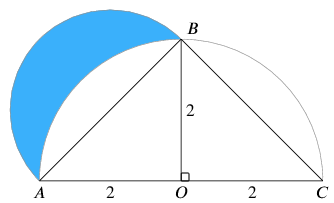

To find the area of the lune, we can find the area of the semicircle with diameter $AB$, and subtract from this the difference between the areas of sector $OAB$ an d triangle $OAB$.

d triangle $OAB$.

Using Pythagoras' theorem on $AOB$, we have $AB = \sqrt{2^2+2^2} = 2 \sqrt{2}$, so the radius of the outer circle of the lune is $\sqrt{2}$.

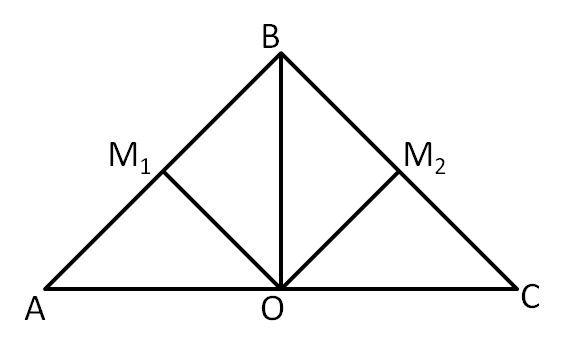

He also demonstrates how to construct the quadrature of the lune:

The quadrature of the lune must have area $2$, so must have side lengths $\sqrt{2}$.

The quadrature of the lune must have area $2$, so must have side lengths $\sqrt{2}$.

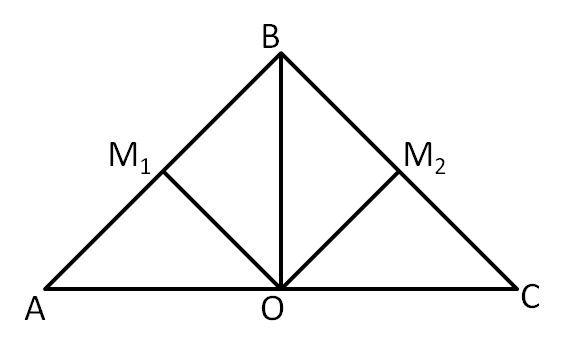

Let $M_1$ and $M_2$ be the midpoints of $AB$ and $AC$ respectively. Then the line $OM_1$ bisects $AB$ at right angles, and likewise for $OM_2$ and $BC$, since they are chords of the circle.

This is then a square, as the angles are all right angles (we know that $M_1BM_2$ is a right angle because it is subtended in a semicircle) and $M_1B = M_2B = \sqrt{2}$.

This square has the same area as the lune, and therefore is the quadrature of the lune.

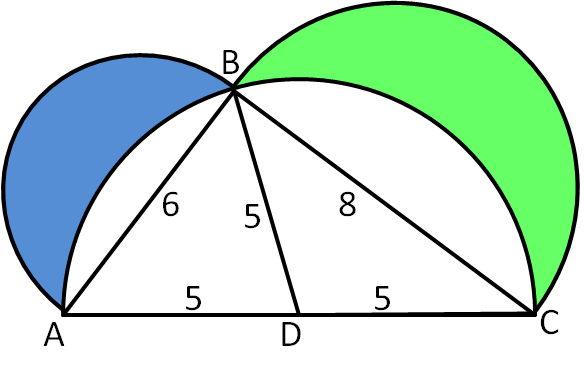

Kristian, from Maidstone Grammar School, was able to use the same method to answer question 2. Here is his solution:

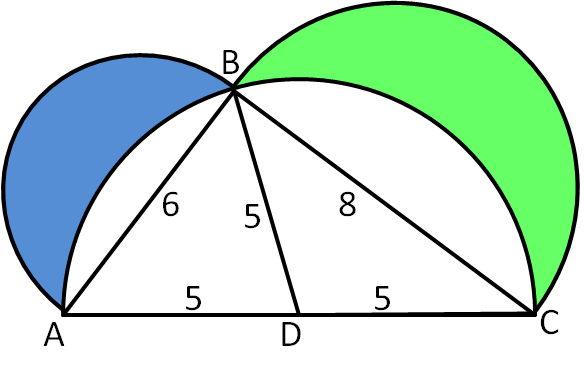

Let $D$ be the midpoint of $AC$, this is distance $5$ from $A$, $B$ and $C$.

Let $D$ be the midpoint of $AC$, this is distance $5$ from $A$, $B$ and $C$.

The angle $B\hat{C}A$ can be calculated using trigonometry, to be $B\hat{C}A = \mathrm{cos}^{-1}\left(\frac{8}{10}\right) = 36.86...^\circ$.

Then, using the circle theorem that the angle subtended at the centre is twice that subtended at the circumference, $B\hat{D}A = 2B\hat{C}A = 73.73...^\circ$.

The triangle $ADB$ has area $\frac{1}{2} \times 5 \times 5 \times \mathrm{sin}\left( 73.73... \right) = 12$, using the formula for the area of a triangle.

The segment between $A$ and $B$ has area $16.08... - 12 = 4.08...$.

Then, the semicircle with diameter $AB$ has area $\frac{1}{2} \times \pi \times 3^2 = 14.13...$.

This means: $$\text{Area of Lune} = \text{Area of Semicircle} - \text{Area of Segment} = 14.13... - 4.08... = 10.049... $$

The triangle $CDB$ has area $\frac{1}{2} \times 5 \times 5 \times \mathrm{sin}\left( 106.26... \right) = 12$, using the formula for the area of a triangle.

The segment between $B$ and $C$ has area $23.18... - 12 = 11.18...$.

Then, the semicircle with diameter $BC$ has area $\frac{1}{2} \times \pi \times 4^2 = 25.13...$.

This means: $$\text{Area of Lune} = \text{Area of Semicircle} - \text{Area of Segment} = 25.13... - 11.18... = 13.95... $$

Therefore, the total lune area is: $$\text{Total Lune Area} = \text{Blue Lune Area} + \text{Green Lune Area} = 10.049... + 13.95... = 24$$

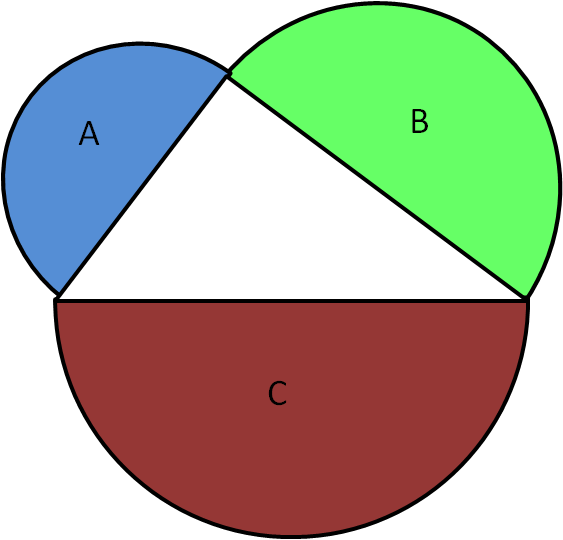

Joe, from Leventhorpe School, found the result in a very nice way, which explains why the area that Kristian found was an integer. Joe was able to show that the area of the two lunes adds up to give the area of the original triangle. Here is his working:

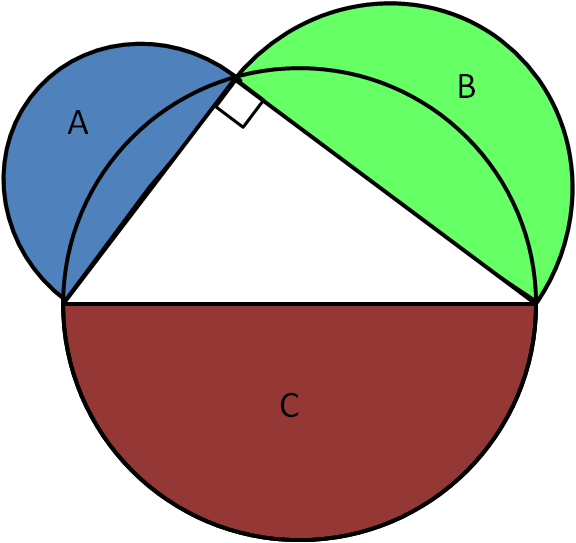

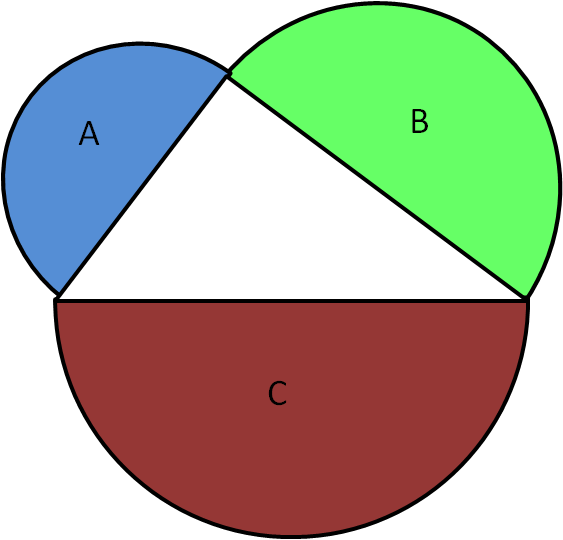

If a right angled triangle has sides $a$, $b$ and $c$, where $c$ is the hypotenuse, Pythagoras' Theorem states that $a^2+b^2=c^2$. This can be applied to the areas of squares constructed on the sides, but this also applies to any shape, as long as those constructed on the

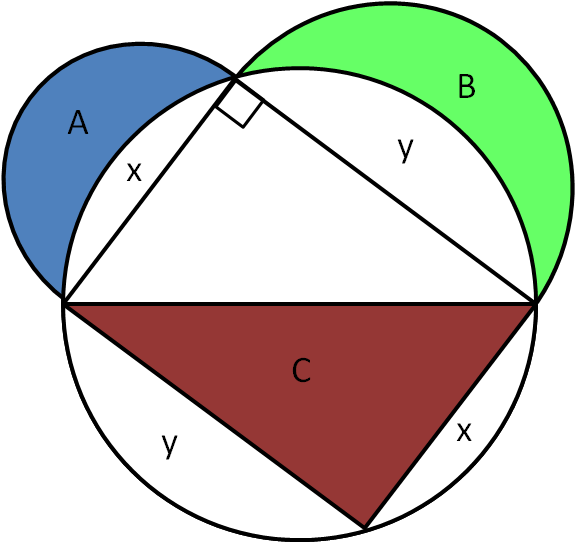

three sides are similar. Suppose we do this with semicircles. In the diagram, the areas of semicircles A and B add to give that of semicircle C.

If a right angled triangle has sides $a$, $b$ and $c$, where $c$ is the hypotenuse, Pythagoras' Theorem states that $a^2+b^2=c^2$. This can be applied to the areas of squares constructed on the sides, but this also applies to any shape, as long as those constructed on the

three sides are similar. Suppose we do this with semicircles. In the diagram, the areas of semicircles A and B add to give that of semicircle C.

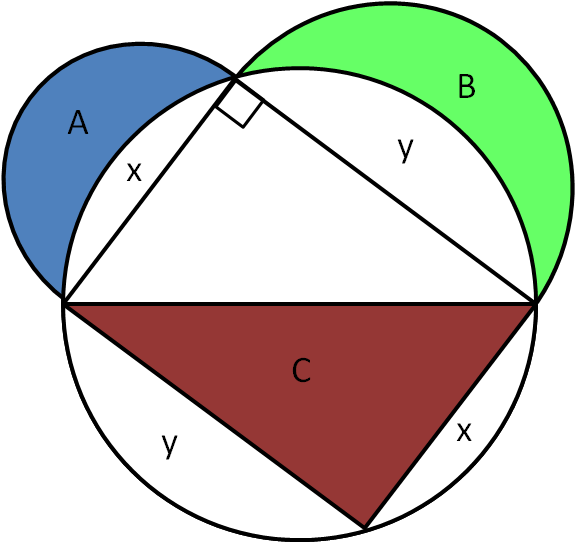

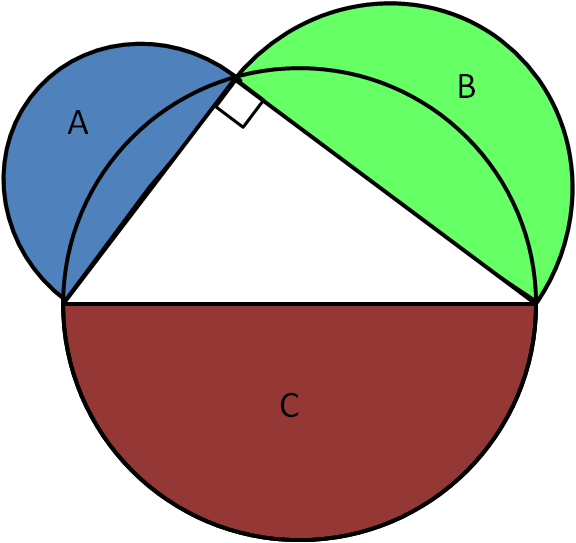

The triangle formed in this diagram is certainly right-angled, as it is subtended in a semi-circle.

The triangle formed in this diagram is certainly right-angled, as it is subtended in a semi-circle.

Rotating the triangle by $180^\circ$ in the circle, the segments labelled as $x$ are the same, as are those labelled as $y$.

Rotating the triangle by $180^\circ$ in the circle, the segments labelled as $x$ are the same, as are those labelled as $y$.

Subtracting this from the equality of areas established above, this gives that $A + B = C$ in the diagram to the right. Since rotating does not change the area, this says that the original triangle had the same area as the two lunes.

Joe was then able to use this to establish that the total area of the lunes in question 2 was $24$, the area of the triangle. He also adapted this to question 1:

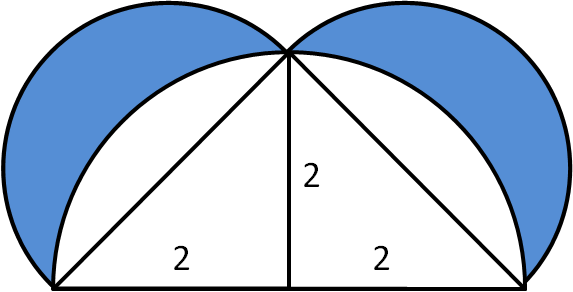

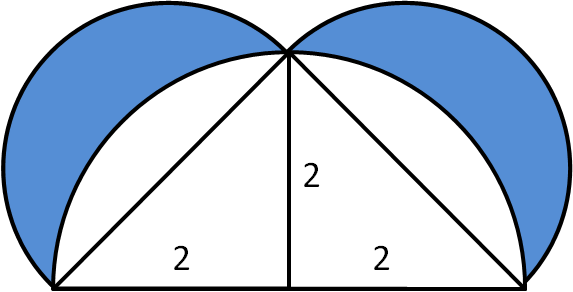

The two lunes in the diagram have the same area, as the right angled triangle is isosceles. The triangle has area $\frac{1}{2} \times 2 \times 4 = 4$, so each lune has area $2$.

The two lunes in the diagram have the same area, as the right angled triangle is isosceles. The triangle has area $\frac{1}{2} \times 2 \times 4 = 4$, so each lune has area $2$.

Thank you and well done to everyone who contributed their solutions to this problem

To find the area of the lune, we can find the area of the semicircle with diameter $AB$, and subtract from this the difference between the areas of sector $OAB$ an

d triangle $OAB$.

d triangle $OAB$.Using Pythagoras' theorem on $AOB$, we have $AB = \sqrt{2^2+2^2} = 2 \sqrt{2}$, so the radius of the outer circle of the lune is $\sqrt{2}$.

- Semicircle area: $\frac{\pi r^2}{2} = \frac{\pi \left( \sqrt{2} \right)^2}{2} = \pi $

- Sector area: $\frac{\pi r^2}{4} = \frac{\pi \left( 2 \right) ^ 2}{4} = \pi $

- Triangle area: $\frac{1}{2}bh = \frac{1}{2} \times 2 \times 2 = 2$

He also demonstrates how to construct the quadrature of the lune:

The quadrature of the lune must have area $2$, so must have side lengths $\sqrt{2}$.

The quadrature of the lune must have area $2$, so must have side lengths $\sqrt{2}$.Let $M_1$ and $M_2$ be the midpoints of $AB$ and $AC$ respectively. Then the line $OM_1$ bisects $AB$ at right angles, and likewise for $OM_2$ and $BC$, since they are chords of the circle.

This is then a square, as the angles are all right angles (we know that $M_1BM_2$ is a right angle because it is subtended in a semicircle) and $M_1B = M_2B = \sqrt{2}$.

This square has the same area as the lune, and therefore is the quadrature of the lune.

Kristian, from Maidstone Grammar School, was able to use the same method to answer question 2. Here is his solution:

Let $D$ be the midpoint of $AC$, this is distance $5$ from $A$, $B$ and $C$.

Let $D$ be the midpoint of $AC$, this is distance $5$ from $A$, $B$ and $C$.The angle $B\hat{C}A$ can be calculated using trigonometry, to be $B\hat{C}A = \mathrm{cos}^{-1}\left(\frac{8}{10}\right) = 36.86...^\circ$.

Then, using the circle theorem that the angle subtended at the centre is twice that subtended at the circumference, $B\hat{D}A = 2B\hat{C}A = 73.73...^\circ$.

Blue Lune

The sector $ADB$ has area $\frac{A\hat{D}B}{360}\pi r^2 = \frac{73.73...}{360} \times \pi \times 5^2 = 16.08...$.The triangle $ADB$ has area $\frac{1}{2} \times 5 \times 5 \times \mathrm{sin}\left( 73.73... \right) = 12$, using the formula for the area of a triangle.

The segment between $A$ and $B$ has area $16.08... - 12 = 4.08...$.

Then, the semicircle with diameter $AB$ has area $\frac{1}{2} \times \pi \times 3^2 = 14.13...$.

This means: $$\text{Area of Lune} = \text{Area of Semicircle} - \text{Area of Segment} = 14.13... - 4.08... = 10.049... $$

Green Lune

The sector $CDB$ has area $\frac{C\hat{D}B}{360}\pi r^2 = \frac{106.26...}{360} \times \pi \times 5^2 = 23.18...$.The triangle $CDB$ has area $\frac{1}{2} \times 5 \times 5 \times \mathrm{sin}\left( 106.26... \right) = 12$, using the formula for the area of a triangle.

The segment between $B$ and $C$ has area $23.18... - 12 = 11.18...$.

Then, the semicircle with diameter $BC$ has area $\frac{1}{2} \times \pi \times 4^2 = 25.13...$.

This means: $$\text{Area of Lune} = \text{Area of Semicircle} - \text{Area of Segment} = 25.13... - 11.18... = 13.95... $$

Therefore, the total lune area is: $$\text{Total Lune Area} = \text{Blue Lune Area} + \text{Green Lune Area} = 10.049... + 13.95... = 24$$

Joe, from Leventhorpe School, found the result in a very nice way, which explains why the area that Kristian found was an integer. Joe was able to show that the area of the two lunes adds up to give the area of the original triangle. Here is his working:

If a right angled triangle has sides $a$, $b$ and $c$, where $c$ is the hypotenuse, Pythagoras' Theorem states that $a^2+b^2=c^2$. This can be applied to the areas of squares constructed on the sides, but this also applies to any shape, as long as those constructed on the

three sides are similar. Suppose we do this with semicircles. In the diagram, the areas of semicircles A and B add to give that of semicircle C.

If a right angled triangle has sides $a$, $b$ and $c$, where $c$ is the hypotenuse, Pythagoras' Theorem states that $a^2+b^2=c^2$. This can be applied to the areas of squares constructed on the sides, but this also applies to any shape, as long as those constructed on the

three sides are similar. Suppose we do this with semicircles. In the diagram, the areas of semicircles A and B add to give that of semicircle C. The triangle formed in this diagram is certainly right-angled, as it is subtended in a semi-circle.

The triangle formed in this diagram is certainly right-angled, as it is subtended in a semi-circle. Rotating the triangle by $180^\circ$ in the circle, the segments labelled as $x$ are the same, as are those labelled as $y$.

Rotating the triangle by $180^\circ$ in the circle, the segments labelled as $x$ are the same, as are those labelled as $y$.Subtracting this from the equality of areas established above, this gives that $A + B = C$ in the diagram to the right. Since rotating does not change the area, this says that the original triangle had the same area as the two lunes.

Joe was then able to use this to establish that the total area of the lunes in question 2 was $24$, the area of the triangle. He also adapted this to question 1:

The two lunes in the diagram have the same area, as the right angled triangle is isosceles. The triangle has area $\frac{1}{2} \times 2 \times 4 = 4$, so each lune has area $2$.

The two lunes in the diagram have the same area, as the right angled triangle is isosceles. The triangle has area $\frac{1}{2} \times 2 \times 4 = 4$, so each lune has area $2$.Thank you and well done to everyone who contributed their solutions to this problem

You may also like

Powerful Quadratics

This comes in two parts, with the first being less fiendish than the second. It’s great for practising both quadratics and laws of indices, and you can get a lot from making sure that you find all the solutions. For a real challenge (requiring a bit more knowledge), you could consider finding the complex solutions.

Discriminating

You're invited to decide whether statements about the number of solutions of a quadratic equation are always, sometimes or never true.

Factorisable Quadratics

This will encourage you to think about whether all quadratics can be factorised and to develop a better understanding of the effect that changing the coefficients has on the factorised form.