Skip over navigation

Thank you to Minhaj from St Ivo School for his very thorough solution to this problem.

Here is his solution to the warm up problem:

Minhaj thought of a few different ways to convince himself that $\frac{2}{5}$ is bigger than $\frac{1}{3}$

1. The lowest common denominator for $\frac{2}{5}$ and $\frac{1}{3}$ is $15$ and hence $\frac{2}{5}$ can be written as $\frac{6}{15}$ and $\frac{1}{3}$ can be written as $\frac{5}{15}$. It can now be seen that $\frac{2}{5} > \frac{1}{3}$ because when the denominator is $15$ for both fractions, the numerator is $1$ number larger for the fraction equivalent to $\frac{2}{5}$ which is $\frac{6}{15}$

2. If you were to simply do the division for both fractions, you would get $\frac{2}{5}= 0.4$ and $\frac{1}{3}= 0.3333”¦.$ Since the number in the tenths place for $\frac{2}{5}$ is $4$ and for $\frac{1}{3}$ it is $3$, this again shows that $\frac{2}{5}> \frac{1}{3}$ as $4$ is bigger than $3$

3. Imagine you got a string which has a length of 15cm. If you cut $\frac{2}{5}$ of this string, then you would a length of 6cm. If you cut $\frac{1}{3}$ of this string then you would get a length of 5cm. This also shows that $\frac{2}{5}> \frac{1}{3}$ as $\frac{2}{5}$ of $15$ is larger than $\frac{1}{3}$ of $15$. You can use this idea with any length or any other instance (e.g. time)

What if you had the fractions $\frac{2x}{5}$ and $\frac{x}{3}$?

The answer would only be the same if $x$ is some positive number which is not $0$. You can think of $\frac{2x}{5}$ as $x \times \frac{2}{5}$ and you can think of $\frac{x}{3}$ as $x \times \frac{1}{3}$. We have already established that $\frac{2}{5}>\frac{1}{3}$ and hence if $x$ is some positive constant which is not zero, the fractions are just getting multiplied by a fixed value and hence they are only getting scaled up or down at the same rate. If $x=0$, then $\frac{2x}{5}=\frac{x}{3}$ because you end up with a $0$ on the numerator for both fractions and $0$ divided $5$ or $3$ is just $0$. It gets interesting when $x$ is negative. If $x$ is negative, then $\frac{x}{3}> \frac{2x}{5}$. Because $\frac{2}{5}$ is bigger than $\frac{1}{3}$, this means if you multiply $\frac{2}{5}$ by a negative number, then the number is larger on the negative side (it is further down the number line on the negative side than $\frac{x}{3}$). What this consequently means is that $\frac{2x}{5}$ is smaller than $\frac{x}{3}$ as $\frac{x}{3}$ would be closer to $0$.

Here is Minhaj's solution to the main problem

$\frac{4x}{7}$ or $\frac{9}{14}$

$\frac{4x}{7}$ can be written as $\frac{8x}{14}$; this makes the denominators for both fractions the same and we only need to focus on the numerators. The only time these fractions are equal is when $8x=9$ and so when $x=\frac{9}{8}$ or $1.125$ then the fractions are equal. If $x$ is greater than $\frac{9}{8}$, then this means that $\frac{4x}{7}> \frac{9}{14}$. However if $x< 1.125$ then $\frac{9}{14}> \frac{4x}{7}$.

$\frac{5}{9}$ or $\frac{2x}{12}$

Again we should try to get the lowest common denominator. In this case it is $36$ and so $\frac{5}{9}= \frac{20}{36}$ and $\frac{2x}{12}= \frac{6x}{36}$. Same like last time, the only time the fractions are the same is if the numerators are equal. So when $6x=20$ and $x= \frac{10}{3}$, then $\frac{5}{9}= \frac{2x}{12}$. If $x$ is greater than $\frac{10}{3}$, then $\frac{2x}{12}> \frac{5}{9}$ but if $x$ is less than $\frac{10}{3}$ then $\frac{5}{9}> \frac{2x}{12}$.

$\frac{3x}{4}+1$ or $\frac{x}{4}+3$

$(\frac{3x}{4})+1= (\frac{3x}{4})+(\frac{4}{4})= \frac{3x+4}{4}$,

$(\frac{x}{4})+3= (\frac{x}{4})+(\frac{12}{4})= \frac{x+12}{4}$. Both of the fractions have already got a common denominator and so when $3x+4=x+12$ i.e. $x=4$, then the fractions are the same as they got the same numerator (this is solving both linear expressions simultaneously). For $(\frac{3x}{4})+1$ to be greater than $(\frac{x}{4})+3$, then this means that $3x+4$ must be greater than $x+12$- in other words $x$ must be greater than $4$. Conversely, if $x<4$, then $(\frac{x}{4})+3 > (\frac{3x}{4})+1$.

$\frac{8(1-x)}{5}$ or $\frac{x}{6}$

$\frac{8(1-x)}{5}= \frac{8-8x}{5}= \frac{48-48x}{30}$ and $\frac{x}{6}=\frac{5x}{30}$. The denominators are now the same so when the numerators are the same- when $48-48x=5x$ i.e. $x=\frac{48}{53}$, then the fractions are the same so $\frac{8(1-x)}{5}= \frac{x}{6}$. If $5x> 48-48x$ i.e. $x> \frac{48}{53}$, then $\frac{x}{6}> \frac{8(1-x)}{5}$. Conversely if $48-48x> 5x$ i.e. $x<\frac{48}{53}$, then $\frac{8(1-x)}{5}> \frac{x}{6}$.

$\frac{8}{2x}$ or $\frac{4x}{16}$

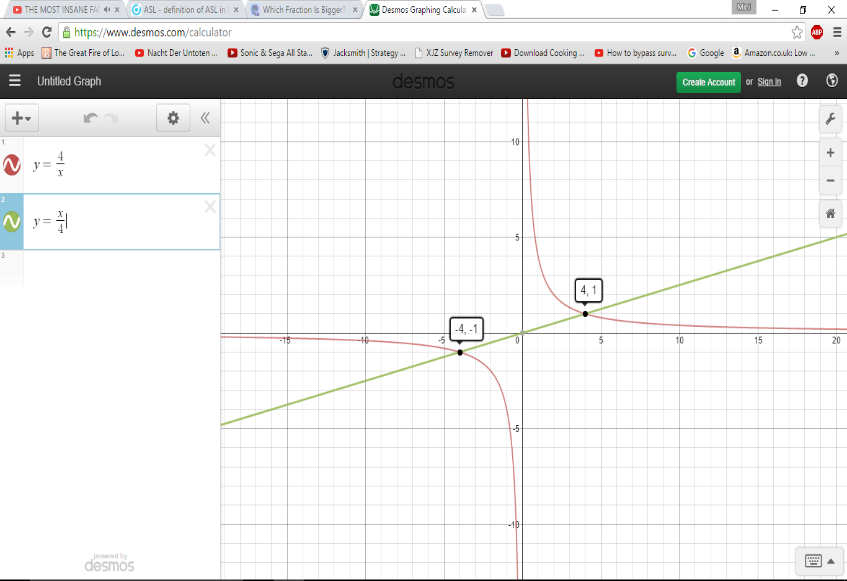

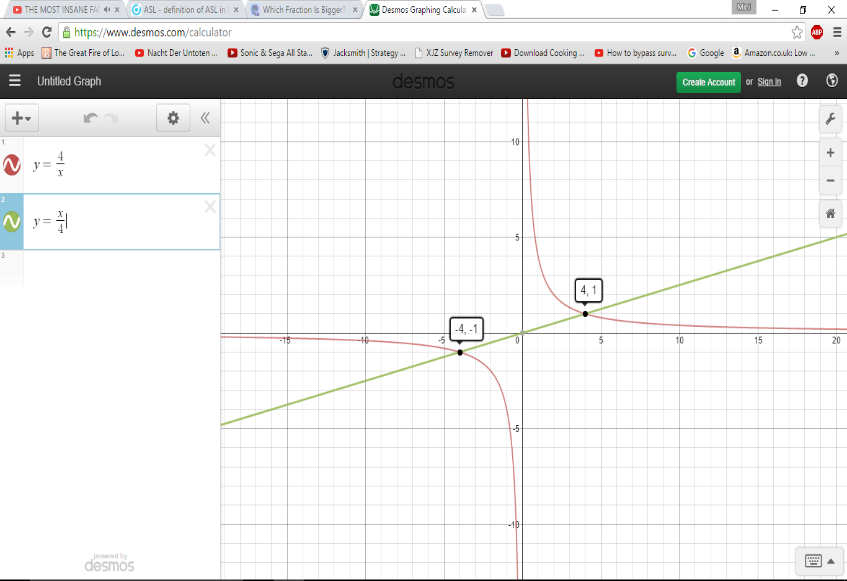

$\frac{8}{2x}= \frac{4}{x}$ and $\frac{4x}{16}=\frac{x}{4}$- so it can be seen that we are comparing the reciprocals of one another where $y=\frac{8}{2x}$ is a reciprocal graph and $y=\frac{4x}{16}$ is a linear graph with a gradient of $\frac{1}{4}$. For the two fractions to be equal, then $\frac{4}{x}$ must be equal to $\frac{x}{4}$. This means $x^2=16$ and so $x=4$ or $x=-4$. This makes sense as $\frac{4}{-4}= \frac{-4}{4}=-1$ and $\frac{4}{4}=\frac{4}{4}=1$ (you get this by substituting $x=4$ or $-4$ into the functions).

As can be seen by looking at the graph above, $\frac{4x}{16}>\frac{8}{2x}$ if $-4 < x < 0$ or $x > 4$, and $\frac{8}{2x}>\frac{4x}{16}$ when $0 < x < 4$ or $x < -4$

In the last case the fractions are incomparable when $x=0$ as $\frac{8}{2x}$ is not defined when $x=0$

Or search by topic

Number and algebra

Geometry and measure

Probability and statistics

Working mathematically

Advanced mathematics

For younger learners

Which Fraction Is Bigger?

Age 16 to 18

Challenge Level

- Problem

- Student Solutions

Thank you to Minhaj from St Ivo School for his very thorough solution to this problem.

Here is his solution to the warm up problem:

Minhaj thought of a few different ways to convince himself that $\frac{2}{5}$ is bigger than $\frac{1}{3}$

1. The lowest common denominator for $\frac{2}{5}$ and $\frac{1}{3}$ is $15$ and hence $\frac{2}{5}$ can be written as $\frac{6}{15}$ and $\frac{1}{3}$ can be written as $\frac{5}{15}$. It can now be seen that $\frac{2}{5} > \frac{1}{3}$ because when the denominator is $15$ for both fractions, the numerator is $1$ number larger for the fraction equivalent to $\frac{2}{5}$ which is $\frac{6}{15}$

2. If you were to simply do the division for both fractions, you would get $\frac{2}{5}= 0.4$ and $\frac{1}{3}= 0.3333”¦.$ Since the number in the tenths place for $\frac{2}{5}$ is $4$ and for $\frac{1}{3}$ it is $3$, this again shows that $\frac{2}{5}> \frac{1}{3}$ as $4$ is bigger than $3$

3. Imagine you got a string which has a length of 15cm. If you cut $\frac{2}{5}$ of this string, then you would a length of 6cm. If you cut $\frac{1}{3}$ of this string then you would get a length of 5cm. This also shows that $\frac{2}{5}> \frac{1}{3}$ as $\frac{2}{5}$ of $15$ is larger than $\frac{1}{3}$ of $15$. You can use this idea with any length or any other instance (e.g. time)

What if you had the fractions $\frac{2x}{5}$ and $\frac{x}{3}$?

The answer would only be the same if $x$ is some positive number which is not $0$. You can think of $\frac{2x}{5}$ as $x \times \frac{2}{5}$ and you can think of $\frac{x}{3}$ as $x \times \frac{1}{3}$. We have already established that $\frac{2}{5}>\frac{1}{3}$ and hence if $x$ is some positive constant which is not zero, the fractions are just getting multiplied by a fixed value and hence they are only getting scaled up or down at the same rate. If $x=0$, then $\frac{2x}{5}=\frac{x}{3}$ because you end up with a $0$ on the numerator for both fractions and $0$ divided $5$ or $3$ is just $0$. It gets interesting when $x$ is negative. If $x$ is negative, then $\frac{x}{3}> \frac{2x}{5}$. Because $\frac{2}{5}$ is bigger than $\frac{1}{3}$, this means if you multiply $\frac{2}{5}$ by a negative number, then the number is larger on the negative side (it is further down the number line on the negative side than $\frac{x}{3}$). What this consequently means is that $\frac{2x}{5}$ is smaller than $\frac{x}{3}$ as $\frac{x}{3}$ would be closer to $0$.

Here is Minhaj's solution to the main problem

$\frac{4x}{7}$ or $\frac{9}{14}$

$\frac{4x}{7}$ can be written as $\frac{8x}{14}$; this makes the denominators for both fractions the same and we only need to focus on the numerators. The only time these fractions are equal is when $8x=9$ and so when $x=\frac{9}{8}$ or $1.125$ then the fractions are equal. If $x$ is greater than $\frac{9}{8}$, then this means that $\frac{4x}{7}> \frac{9}{14}$. However if $x< 1.125$ then $\frac{9}{14}> \frac{4x}{7}$.

$\frac{5}{9}$ or $\frac{2x}{12}$

Again we should try to get the lowest common denominator. In this case it is $36$ and so $\frac{5}{9}= \frac{20}{36}$ and $\frac{2x}{12}= \frac{6x}{36}$. Same like last time, the only time the fractions are the same is if the numerators are equal. So when $6x=20$ and $x= \frac{10}{3}$, then $\frac{5}{9}= \frac{2x}{12}$. If $x$ is greater than $\frac{10}{3}$, then $\frac{2x}{12}> \frac{5}{9}$ but if $x$ is less than $\frac{10}{3}$ then $\frac{5}{9}> \frac{2x}{12}$.

$\frac{3x}{4}+1$ or $\frac{x}{4}+3$

$(\frac{3x}{4})+1= (\frac{3x}{4})+(\frac{4}{4})= \frac{3x+4}{4}$,

$(\frac{x}{4})+3= (\frac{x}{4})+(\frac{12}{4})= \frac{x+12}{4}$. Both of the fractions have already got a common denominator and so when $3x+4=x+12$ i.e. $x=4$, then the fractions are the same as they got the same numerator (this is solving both linear expressions simultaneously). For $(\frac{3x}{4})+1$ to be greater than $(\frac{x}{4})+3$, then this means that $3x+4$ must be greater than $x+12$- in other words $x$ must be greater than $4$. Conversely, if $x<4$, then $(\frac{x}{4})+3 > (\frac{3x}{4})+1$.

$\frac{8(1-x)}{5}$ or $\frac{x}{6}$

$\frac{8(1-x)}{5}= \frac{8-8x}{5}= \frac{48-48x}{30}$ and $\frac{x}{6}=\frac{5x}{30}$. The denominators are now the same so when the numerators are the same- when $48-48x=5x$ i.e. $x=\frac{48}{53}$, then the fractions are the same so $\frac{8(1-x)}{5}= \frac{x}{6}$. If $5x> 48-48x$ i.e. $x> \frac{48}{53}$, then $\frac{x}{6}> \frac{8(1-x)}{5}$. Conversely if $48-48x> 5x$ i.e. $x<\frac{48}{53}$, then $\frac{8(1-x)}{5}> \frac{x}{6}$.

$\frac{8}{2x}$ or $\frac{4x}{16}$

$\frac{8}{2x}= \frac{4}{x}$ and $\frac{4x}{16}=\frac{x}{4}$- so it can be seen that we are comparing the reciprocals of one another where $y=\frac{8}{2x}$ is a reciprocal graph and $y=\frac{4x}{16}$ is a linear graph with a gradient of $\frac{1}{4}$. For the two fractions to be equal, then $\frac{4}{x}$ must be equal to $\frac{x}{4}$. This means $x^2=16$ and so $x=4$ or $x=-4$. This makes sense as $\frac{4}{-4}= \frac{-4}{4}=-1$ and $\frac{4}{4}=\frac{4}{4}=1$ (you get this by substituting $x=4$ or $-4$ into the functions).

As can be seen by looking at the graph above, $\frac{4x}{16}>\frac{8}{2x}$ if $-4 < x < 0$ or $x > 4$, and $\frac{8}{2x}>\frac{4x}{16}$ when $0 < x < 4$ or $x < -4$

In the last case the fractions are incomparable when $x=0$ as $\frac{8}{2x}$ is not defined when $x=0$

You may also like

Powerful Quadratics

This comes in two parts, with the first being less fiendish than the second. It’s great for practising both quadratics and laws of indices, and you can get a lot from making sure that you find all the solutions. For a real challenge (requiring a bit more knowledge), you could consider finding the complex solutions.

Discriminating

You're invited to decide whether statements about the number of solutions of a quadratic equation are always, sometimes or never true.

Factorisable Quadratics

This will encourage you to think about whether all quadratics can be factorised and to develop a better understanding of the effect that changing the coefficients has on the factorised form.