Skip over navigation

Eleanor from English Martyrs Hartlepool and Jaro, Giulia and Pasan from St Louis School of Milan have tackled the problem of which is bigger out of $2^x$ and $x^2$.

Eleanor has started by considering a few specific values of $x$ to get an idea for what happens.

$2^0 > 0^2$ $1>0$

$2^1 > 1^2$ $2>1$

$2^2 = 2^2$ $4=4$

$2^3 < 3^2$ $8<9$

$2^4 = 4^2$ $16=16$

The main thing we notice here is that the answer depends on $x$.

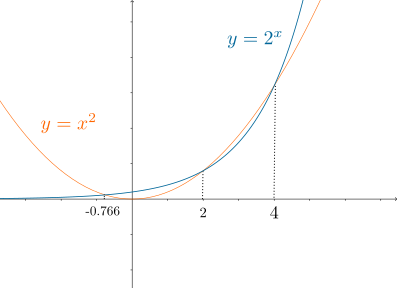

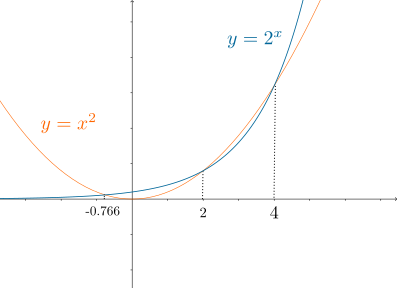

Jaro, Giulian and Pasan have considered how the answer depends on $x$ more generally by considering the graphs of $2^x$ and $x^2$

To find out which one was bigger we drew a graph on which we could clearly

see the point of intersections of the two functions, of which there were 3, when

$x=-0.766, 2 \text{ and } 4$. Then, we reached the conclusion that:

- when $x$ is bigger than $4$, $2^x$ is bigger than $x^2$

- when $x$ is smaller than $4$ but bigger than $2$, $2^x$ is smaller than $x^2$

- when $x$ is smaller than $2$ but bigger than $-0.766$, $2^x$ is bigger than $x^2$

- when $x$ is smaller than $-0.766$, $2^x$ is smaller than $x^2$

They also compared the graphs $3^x$ and $x^3$ as a first step to considering the general case of comparing $a^x$ and $x^a$ and found that there were again two positive intersections, this time at $x=2.48 \text{ and }3$.

Pablo and Sergio from King College of Alicante and Peter from Durham Johnston school, have made good starts on considering what happens for general $a$.

Both Peter and Pablo have made the good observatioin that $x=a$ will always be one of the points of intersection, because $x=a$ is always a solution to $x^a=a^x$.

But is it the case, for any value of $a$, that there are always two intersections of the graphs at positive $x$ values?

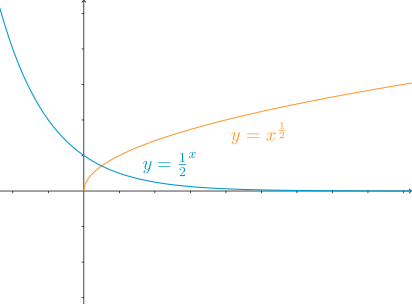

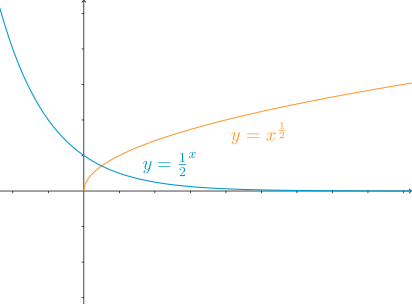

Sergio has solved completely the case where $0 < a \le 1$, and found there is only one intersection in this case.

In the case $0 < a \le 1$, If $x$ is smaller than $a$ then $a^x$ has a higher value than $x^a$, whereas if $x$ is bigger than $a$, $x^a$ would alway be bigger than $a^x$.

Thomas from BHASVIC Sixth Form College Brighton has finished the solution for $a>1$:

At $x=0$ for $a > 1$ we have $0=x^a < a^x=1$. Think of the two graphs $y_1 = x^a$ and $y_2 = a^x$. As $x$ increases, we certainly have an intersection at $x=a$; the gradients of the curves here are $\frac{dy_1}{dx} = a^a$ and $\frac{dy_2}{dx} = a^a \ln a$ respectively. There are now 3 cases:

For $1 < a < e$ the gradient of $y_1$ is steeper than $y_2$ here, so $y_2$ must pass from above $y_1$ just before $x=a$ to below it just after $x=a$. We know that for large $x$, $y_2 > y_1$ so there must be a second intersection point somewhere for $x > a$.

For $a > e$ the gradient of $y_2$ is steeper than $y_1$ here, so $y_2$ passes from below $y_1$ before $x=a$ to above it after $x=a$. At $x=0$, $y_2 > y_1$ so the two curves must cross again somewhere in $0 < x < a$.

For $a=e$ the two curves just touch. There are no other intersections other than $x=a$.

So there is only one number $a > 1$ where we don't have at least two points where $a^x=x^a$.

Or search by topic

Number and algebra

Geometry and measure

Probability and statistics

Working mathematically

Advanced mathematics

For younger learners

How Fast Does it Grow?

Age 16 to 18

Challenge Level

- Problem

- Getting Started

- Student Solutions

Eleanor from English Martyrs Hartlepool and Jaro, Giulia and Pasan from St Louis School of Milan have tackled the problem of which is bigger out of $2^x$ and $x^2$.

Eleanor has started by considering a few specific values of $x$ to get an idea for what happens.

$2^0 > 0^2$ $1>0$

$2^1 > 1^2$ $2>1$

$2^2 = 2^2$ $4=4$

$2^3 < 3^2$ $8<9$

$2^4 = 4^2$ $16=16$

The main thing we notice here is that the answer depends on $x$.

Jaro, Giulian and Pasan have considered how the answer depends on $x$ more generally by considering the graphs of $2^x$ and $x^2$

To find out which one was bigger we drew a graph on which we could clearly

see the point of intersections of the two functions, of which there were 3, when

$x=-0.766, 2 \text{ and } 4$. Then, we reached the conclusion that:

- when $x$ is bigger than $4$, $2^x$ is bigger than $x^2$

- when $x$ is smaller than $4$ but bigger than $2$, $2^x$ is smaller than $x^2$

- when $x$ is smaller than $2$ but bigger than $-0.766$, $2^x$ is bigger than $x^2$

- when $x$ is smaller than $-0.766$, $2^x$ is smaller than $x^2$

They also compared the graphs $3^x$ and $x^3$ as a first step to considering the general case of comparing $a^x$ and $x^a$ and found that there were again two positive intersections, this time at $x=2.48 \text{ and }3$.

Pablo and Sergio from King College of Alicante and Peter from Durham Johnston school, have made good starts on considering what happens for general $a$.

Both Peter and Pablo have made the good observatioin that $x=a$ will always be one of the points of intersection, because $x=a$ is always a solution to $x^a=a^x$.

But is it the case, for any value of $a$, that there are always two intersections of the graphs at positive $x$ values?

Sergio has solved completely the case where $0 < a \le 1$, and found there is only one intersection in this case.

In the case $0 < a \le 1$, If $x$ is smaller than $a$ then $a^x$ has a higher value than $x^a$, whereas if $x$ is bigger than $a$, $x^a$ would alway be bigger than $a^x$.

Thomas from BHASVIC Sixth Form College Brighton has finished the solution for $a>1$:

At $x=0$ for $a > 1$ we have $0=x^a < a^x=1$. Think of the two graphs $y_1 = x^a$ and $y_2 = a^x$. As $x$ increases, we certainly have an intersection at $x=a$; the gradients of the curves here are $\frac{dy_1}{dx} = a^a$ and $\frac{dy_2}{dx} = a^a \ln a$ respectively. There are now 3 cases:

For $1 < a < e$ the gradient of $y_1$ is steeper than $y_2$ here, so $y_2$ must pass from above $y_1$ just before $x=a$ to below it just after $x=a$. We know that for large $x$, $y_2 > y_1$ so there must be a second intersection point somewhere for $x > a$.

For $a > e$ the gradient of $y_2$ is steeper than $y_1$ here, so $y_2$ passes from below $y_1$ before $x=a$ to above it after $x=a$. At $x=0$, $y_2 > y_1$ so the two curves must cross again somewhere in $0 < x < a$.

For $a=e$ the two curves just touch. There are no other intersections other than $x=a$.

So there is only one number $a > 1$ where we don't have at least two points where $a^x=x^a$.

You may also like

Powerful Quadratics

This comes in two parts, with the first being less fiendish than the second. It’s great for practising both quadratics and laws of indices, and you can get a lot from making sure that you find all the solutions. For a real challenge (requiring a bit more knowledge), you could consider finding the complex solutions.

Discriminating

You're invited to decide whether statements about the number of solutions of a quadratic equation are always, sometimes or never true.

Factorisable Quadratics

This will encourage you to think about whether all quadratics can be factorised and to develop a better understanding of the effect that changing the coefficients has on the factorised form.