Skip over navigation

Article by Janine Davenall

This article was first published in the Association of Teachers of Mathematics journal 'Mathematics Teaching' in November 2015.

In this article, Janine Davenall (a teacher at Netley Primary School in Camden) reports on a small research project which focused on children's personal recordings of mathematics.

The opportunity to reflect on children's personalised mathematical recordings was presented to me during a small research project based in my Reception class. I was interested in how young children interpreted their recordings and related early calculating ideas to everyday situations away from a taught context. These recordings were used as a powerful teaching tool to extend mathematical ideas as individuals talked about their work. What became clear from discussions was how little value number recording seemed to have for these children, and how the dynamic action within their stories was the most important factor to communicate.

Mathematical graphics offer a conceptual link between practical exploration and symbolic representation. By working closely with children while their recordings developed, colleagues and I gained an insight into individuals' mathematical understanding. Children's recordings were viewed as a means of communication, where emergent thinking was expressed. Mathematical mark-making was thereby given a similar status to emergent writing which early years practitioners are familiar with and confident about celebrating and nurturing.

The term 'emergent mathematics' was used by Gifford to describe a move between practical activities that are then represented in children's 'personal ways, gradually adopting standard written forms' (1997) thus offering the potential to value both formal and informal mathematical ideas and methods of recording.

The 2012 Early Years Foundation Stage non-statutory guidance (in use at the time of this project) advised 'A Unique Child - Records, using marks that they can interpret and explain' (2012). The potential for personalised early recording to provide a bridge between mathematics displayed during play, and ideas introduced during structured times, are not explored and thus remain optional and vague. Authors such as Worthington and Carruthers have presented significant evidence to suggest that by working with personalised mathematical graphics practitioners can support children's development as 'informal marks are gradually transformed into standard symbolism' (2003). The rich ideas that children express, and the creative ways that they use numbers and standardised symbols to communicate their ideas, are not cited as examples for Expressive Arts and Design and yet children's mathematical recordings could be used to provide evidence for this goal when they use 'original ways...to represent their own ideas, thoughts' (EYFS, 2012).

Personal recordings, linked with stories, revealed children's emerging ideas of number and calculating and allowed staff to support their understanding and use of standardised symbols. Hughes described the importance of young children understanding the embedded meaning of mathematical language and the need to relate this to symbols when he wrote;

The examples provided here show how creatively children used symbolic representation to communicate with others. With no fixed idea of the journey that an activity would take practitioners were open to observing, and listening to, individual interpretations of a mathematical situation. Final recordings represented only part of the learning moment as graphics were generally accompanied by dialogue. The dramatic action of a story clearly held significant value for the children and their stories were presented with heightened emotion and energy. Children were happy to incorporate standardised symbols within their recordings and they enjoyed the praise given to them by parents and visitors who celebrated recognisable number sentences. However, children's own explanations generally placed limited value on number recording and sometimes it appeared to reduce their ownership of work as numbers generalised their personalised expression.

Digging for dinosaurs

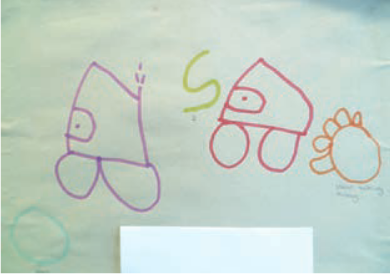

This was an activity where dinosaurs had been hidden in the sandpit. Children were asked to create a sign to explain to a friend the quantity and colour of the dinosaurs they had found. Work revealed how children continued to use idiosyncratic methods of recording quantities, even when they were experienced number writers. The first example shows coloured circles used to represent each dinosaur. The number 8 was only added when I prompted, despite the fact that this child was a confident number writer. This is possibly an early years example of what Hughes observed where children did not incorporate formal knowledge when given the choice. Hughes suggested children 'revealed a striking reluctance to use the conventional symbolism of arithmetic... which they used daily in the classroom' (1986), and suggested that this was possibly because they did not see standard written forms as relevant. Although he was referring to calculating, the relevance of his comment is that this child could have, but did not, choose to use symbolic representation of the total quantity. To communicate the message they chose to use a coloured, iconic representation. Hughes identified that 'there seemed to be a large gap between the children's concrete numerical understanding and their use of formal written symbolism' (1986). The second example shows a child confirming their understanding of the message. They drew a dinosaur, followed by the total quantity '7' and then recorded each colour dinosaur with a corresponding coloured line. These children spoke confidently about their work and peers were able to read, and to interpret, the signs.

Going on holiday

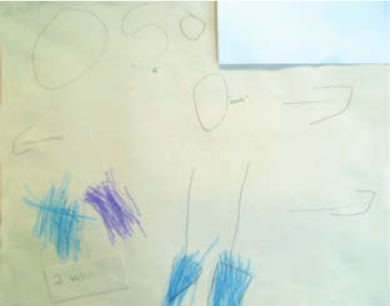

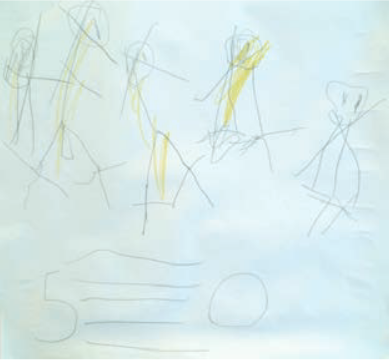

The first work sample here reveals an early attempt to record the operation of subtraction. A hand was drawn to symbolise the action of both cars moving away. When prompted, numerals were confidently written for the original and final amounts (2 reversed and zero). The narrative action of a hand symbolising the operation, has been related to dynamic schematization which could indicate 'higher levels of understanding since they have the potential to show the relationship between drawing and object, sign and meaning transformation' (Carruthers & Worthington, 2008).

The second example shows a child really trying to communicate what was important to them: leaving aeroplanes could fly off in any direction. For this purpose arrows were used as a means of symbolic representation. The numerals 2 (reversed) and 0 were included to show both initial and final amounts, but when this was presented to the class group the mathematical element of this activity were clearly less important than the movement of vehicles and the accompanying story.

During later discussions toy aeroplanes were collected together and used to demonstrate the movement of two planes flying off in all directions.

Baking day

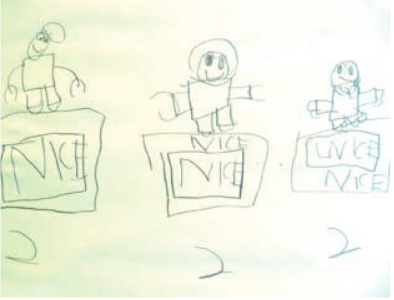

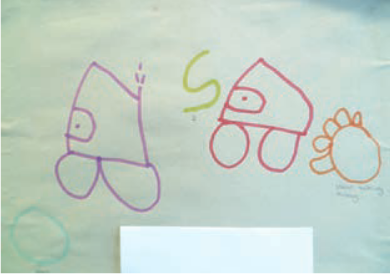

During a biscuit sharing activity, children were challenged to share six biscuits initially between two friends, and then to redistribute them as a third person arrived (activity idea taken from Davis and Pepper, 1992). The activity offered a realistic problem-solving scenario and it was interesting that it was not exclusively number confident children that responded with greater efficiency or confidence to this challenge.

The first example shows a pictographic representation of the problem and when the child talked about their recording they spoke with uncharacteristic ease in front of a small group. The child made use of a 'dealing...action scheme [which was] pre-numeric...: they are capable of being solved by children who are generally not good counters' (Davis and Pepper, 1992). I suspect that I observed a child making use of a developmentally appropriate action, that of sharing out biscuits one-at-a-time until there were none left, rather than engaging with a calculation which encouraged the understanding of the part-whole properties of six.

In contrast, the next example shows a child engaging with the mathematical challenges presented by this problem. It shows the thought processes, and offers with unusual clarity a written explanation of how the problem was seen and interpreted. It captures the different ways that the problem challenged this child. Emergent mathematical ideas are revealed in these graphics which reflect the processes worked through to understand and to communicate this problem. Initially people and biscuits were drawn to represent the final situation.

Methods to record division symbolically were then independently explored. The numeral 6 and three arrows were drawn to indicate how 6 had been divided, 2's were then added to explain the quantity in each group. A personal challenge was then introduced, as 6 was reconstructed in a number sentence using knowledge of multiples of 2 by consecutive adding. This recording shows an understanding of part-whole aspects of a larger number together with recognition of the inverse properties of division and multiplication. This work reflects the number confidence of this particular child and their preferred form of communication where self-initiated play often involved number games.

The third example shows how pictures and standard symbols were used to represent the operation of division. Here, 10 biscuits were used as this represented a more complete set for this child who commented “We don't stop at a 9 group”. Pictures were drawn to illustrate how the biscuits were shared, and an explanation that the odd biscuit was for the grandma who had helped to cook the biscuits. The number sentence was written independently and only incorporates one addition symbol to indicate the operation taking place. Three 3's were written as a set, and the use of an equals sign was used to indicate an action, reflecting what was being said at the time, which was “3 add 3 add 3”.

This work showed the process of thinking and employed standardised symbols to communicate the story. It presented me with an opportunity to review part-whole aspects within numbers and to explore division and multiplication, and to begin to lay the foundations of the idea of their inverse qualities.

Chicken hunt

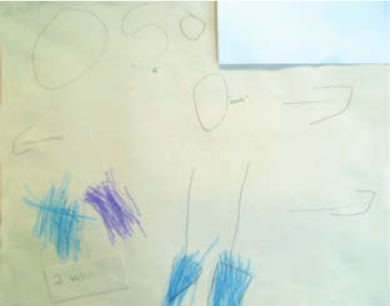

This was an activity that arose from garden play, and a child whose family had recently acquired chickens. I told children the true story of how a Year 1 child's chickens had been attacked by a fox. Using props, I developed a narrative that showed some of the original quantity of chickens being eaten. Learners were then asked to find their own small chickens that I had hidden around our classroom and return to tell, and then record, their own stories.

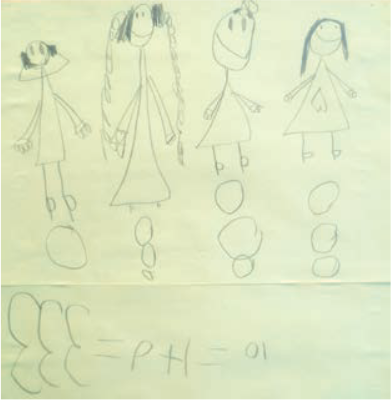

The first sample shows an emergent number sentence incorporating a subtraction symbol to explain the operation. The drawing and the discussion during the picture's evolution was animated and assertive and the absolute priority to be communicated for the reader was for us to understand which chicken was eaten.

An arrow was drawn to explain this, using what Carruthers and Worthington have described as 'narrative action' which they suggest 'appears to support internalized mental images of earlier concrete operations of addition or subtraction calculations: the hand or arrows they include allow them to reflect on the operation and its function' (Carruthers & Worthington, 2008).

I prompted for the number sentence to accompany this story. No reference was made to numerals on the table or around the classroom and “3 - 1 2” (reversing the 2) was written confidently and with independence. The number sentence was said out loud and during the process of recording was acted out using fingers and Makaton to sign 'take away'. This work provides an example of a child successfully bridging their own knowledge of informal and formal symbolic representation for the calculation 3 - 1.

The next example was created by a child who also acted out the number sentence using Makaton for both the '-', and '=' symbols before recording them. A personal priority was given to explaining which chicken was eaten, shown with an 'x' and during a discussion group the author contradicted a friend who pointed to the chicken nearest the fox to explain one had been eaten from a group of five. This detail records the involvement of this child in the story-telling aspect of this activity. Both the picture and the number sentence held an equal importance and this was revealed when they spoke about their work.

The third recording shows the work of a number novice. However, their story was approached confidently and with interest and the recording was quickly completed and then explained to me and another child. Each horizontal line between the 5 and the 0 represented the action of a chicken being taken by the fox. During this discussion the child realised that they had only drawn 4 lines and added 1 more before their work was considered to be complete. This representation reveals an early understanding of subtraction and a generalisation of a standard symbol, adapted for personal expression in an emergent style. While recording, this child did not count down to subtract but counted up from one as they crossed out each chicken to be taken away.

The Chicken Hunt examples provide clear evidence of children understanding subtraction, in that they generated a number-story that started off with one quantity, some components were removed which reduced the final quantity of the group. Carruthers and Worthington suggest:

Mathematical graphics support 'young children's thinking when they are encouraged to use their own ways of representing their personal mathematical meanings' (Worthington, 2007).

I observed that children at the cusp of understanding standardised symbols continued to use personalised methods of recording, when given a choice, for significantly longer than I would initially have anticipated. I also observed that most children at the end of their Reception year used a mixture of number sentences and pictographic recording to communicate their ideas, and that the two methods were used in conjunction with each other to consolidate and explain events.

The project offered a heightened mathematical environment which maintained a playful learning context, with an emphasis on graphical representations as a key feature for the learning progress. Graphical representations were used to stimulate number and calculating discussions, to develop metacognition and as opportunities to link existing knowledge with new ideas and standard written symbols. This approach allowed children to manoeuvre between standardised symbols and personal meanings.

References

Carruthers, E. and Worthington, M. (2008) 'Children's mathematical graphics: young children calculating for meaning', in Thompson, I. (Ed.) Teaching and learning early number, Berkshire: Open University Press (2nd edition)

Davis, G. and Pepper, K. (1992) 'Mathematical Problem Solving by Pre-School Children', Educational Studies in Mathematics, Vol: 23, No:4 August, 397-415

Early Years Foundation Stage (2012) DfEE

Gifford, S. (1997) 'When should they start doing sums? A critical consideration of the 'emergent mathematics' approach', in Thompson, E. (Ed.) Teaching and learning early number, Buckingham: Open University Press

Hughes, M. (1986) Children and Number: Difficulties in Learning Mathematics, Oxford: Blackwell

Worthington, M. and Carruthers, E. (2003) Children's Mathematics: Making Marks, Making Meaning, London: Paul Chapman Publishing

Worthington, M. (2007) 'Multi-modality, play and children's mark-making in maths', in Moyles, J. (Ed.) Early Years Foundations: Meeting the Challenge, Berkshire: Open University Press

If you enjoyed reading this article, you may like to consider purchasing the Young Children Learning Mathematics book, published by the Association of Teachers of Mathematics.

Or search by topic

Number and algebra

Geometry and measure

Probability and statistics

Working mathematically

Advanced mathematics

For younger learners

Age 3 to 7

Published 2016

Young Children's Mathematical Recording

This article was first published in the Association of Teachers of Mathematics journal 'Mathematics Teaching' in November 2015.

In this article, Janine Davenall (a teacher at Netley Primary School in Camden) reports on a small research project which focused on children's personal recordings of mathematics.

The opportunity to reflect on children's personalised mathematical recordings was presented to me during a small research project based in my Reception class. I was interested in how young children interpreted their recordings and related early calculating ideas to everyday situations away from a taught context. These recordings were used as a powerful teaching tool to extend mathematical ideas as individuals talked about their work. What became clear from discussions was how little value number recording seemed to have for these children, and how the dynamic action within their stories was the most important factor to communicate.

Mathematical graphics offer a conceptual link between practical exploration and symbolic representation. By working closely with children while their recordings developed, colleagues and I gained an insight into individuals' mathematical understanding. Children's recordings were viewed as a means of communication, where emergent thinking was expressed. Mathematical mark-making was thereby given a similar status to emergent writing which early years practitioners are familiar with and confident about celebrating and nurturing.

The term 'emergent mathematics' was used by Gifford to describe a move between practical activities that are then represented in children's 'personal ways, gradually adopting standard written forms' (1997) thus offering the potential to value both formal and informal mathematical ideas and methods of recording.

The 2012 Early Years Foundation Stage non-statutory guidance (in use at the time of this project) advised 'A Unique Child - Records, using marks that they can interpret and explain' (2012). The potential for personalised early recording to provide a bridge between mathematics displayed during play, and ideas introduced during structured times, are not explored and thus remain optional and vague. Authors such as Worthington and Carruthers have presented significant evidence to suggest that by working with personalised mathematical graphics practitioners can support children's development as 'informal marks are gradually transformed into standard symbolism' (2003). The rich ideas that children express, and the creative ways that they use numbers and standardised symbols to communicate their ideas, are not cited as examples for Expressive Arts and Design and yet children's mathematical recordings could be used to provide evidence for this goal when they use 'original ways...to represent their own ideas, thoughts' (EYFS, 2012).

Personal recordings, linked with stories, revealed children's emerging ideas of number and calculating and allowed staff to support their understanding and use of standardised symbols. Hughes described the importance of young children understanding the embedded meaning of mathematical language and the need to relate this to symbols when he wrote;

'children must learn to translate between their concrete understanding of number and the written symbolism of arithmetic' (1986).

The examples provided here show how creatively children used symbolic representation to communicate with others. With no fixed idea of the journey that an activity would take practitioners were open to observing, and listening to, individual interpretations of a mathematical situation. Final recordings represented only part of the learning moment as graphics were generally accompanied by dialogue. The dramatic action of a story clearly held significant value for the children and their stories were presented with heightened emotion and energy. Children were happy to incorporate standardised symbols within their recordings and they enjoyed the praise given to them by parents and visitors who celebrated recognisable number sentences. However, children's own explanations generally placed limited value on number recording and sometimes it appeared to reduce their ownership of work as numbers generalised their personalised expression.

Digging for dinosaurs

This was an activity where dinosaurs had been hidden in the sandpit. Children were asked to create a sign to explain to a friend the quantity and colour of the dinosaurs they had found. Work revealed how children continued to use idiosyncratic methods of recording quantities, even when they were experienced number writers. The first example shows coloured circles used to represent each dinosaur. The number 8 was only added when I prompted, despite the fact that this child was a confident number writer. This is possibly an early years example of what Hughes observed where children did not incorporate formal knowledge when given the choice. Hughes suggested children 'revealed a striking reluctance to use the conventional symbolism of arithmetic... which they used daily in the classroom' (1986), and suggested that this was possibly because they did not see standard written forms as relevant. Although he was referring to calculating, the relevance of his comment is that this child could have, but did not, choose to use symbolic representation of the total quantity. To communicate the message they chose to use a coloured, iconic representation. Hughes identified that 'there seemed to be a large gap between the children's concrete numerical understanding and their use of formal written symbolism' (1986). The second example shows a child confirming their understanding of the message. They drew a dinosaur, followed by the total quantity '7' and then recorded each colour dinosaur with a corresponding coloured line. These children spoke confidently about their work and peers were able to read, and to interpret, the signs.

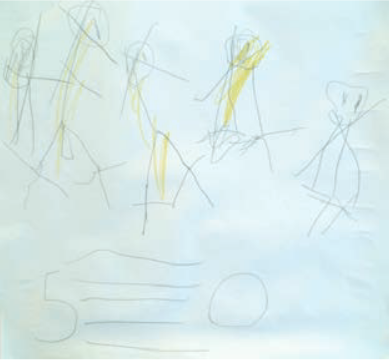

Going on holiday

The first work sample here reveals an early attempt to record the operation of subtraction. A hand was drawn to symbolise the action of both cars moving away. When prompted, numerals were confidently written for the original and final amounts (2 reversed and zero). The narrative action of a hand symbolising the operation, has been related to dynamic schematization which could indicate 'higher levels of understanding since they have the potential to show the relationship between drawing and object, sign and meaning transformation' (Carruthers & Worthington, 2008).

The second example shows a child really trying to communicate what was important to them: leaving aeroplanes could fly off in any direction. For this purpose arrows were used as a means of symbolic representation. The numerals 2 (reversed) and 0 were included to show both initial and final amounts, but when this was presented to the class group the mathematical element of this activity were clearly less important than the movement of vehicles and the accompanying story.

During later discussions toy aeroplanes were collected together and used to demonstrate the movement of two planes flying off in all directions.

Baking day

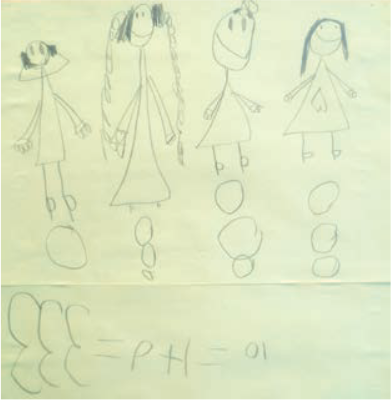

During a biscuit sharing activity, children were challenged to share six biscuits initially between two friends, and then to redistribute them as a third person arrived (activity idea taken from Davis and Pepper, 1992). The activity offered a realistic problem-solving scenario and it was interesting that it was not exclusively number confident children that responded with greater efficiency or confidence to this challenge.

The first example shows a pictographic representation of the problem and when the child talked about their recording they spoke with uncharacteristic ease in front of a small group. The child made use of a 'dealing...action scheme [which was] pre-numeric...: they are capable of being solved by children who are generally not good counters' (Davis and Pepper, 1992). I suspect that I observed a child making use of a developmentally appropriate action, that of sharing out biscuits one-at-a-time until there were none left, rather than engaging with a calculation which encouraged the understanding of the part-whole properties of six.

In contrast, the next example shows a child engaging with the mathematical challenges presented by this problem. It shows the thought processes, and offers with unusual clarity a written explanation of how the problem was seen and interpreted. It captures the different ways that the problem challenged this child. Emergent mathematical ideas are revealed in these graphics which reflect the processes worked through to understand and to communicate this problem. Initially people and biscuits were drawn to represent the final situation.

Methods to record division symbolically were then independently explored. The numeral 6 and three arrows were drawn to indicate how 6 had been divided, 2's were then added to explain the quantity in each group. A personal challenge was then introduced, as 6 was reconstructed in a number sentence using knowledge of multiples of 2 by consecutive adding. This recording shows an understanding of part-whole aspects of a larger number together with recognition of the inverse properties of division and multiplication. This work reflects the number confidence of this particular child and their preferred form of communication where self-initiated play often involved number games.

The third example shows how pictures and standard symbols were used to represent the operation of division. Here, 10 biscuits were used as this represented a more complete set for this child who commented “We don't stop at a 9 group”. Pictures were drawn to illustrate how the biscuits were shared, and an explanation that the odd biscuit was for the grandma who had helped to cook the biscuits. The number sentence was written independently and only incorporates one addition symbol to indicate the operation taking place. Three 3's were written as a set, and the use of an equals sign was used to indicate an action, reflecting what was being said at the time, which was “3 add 3 add 3”.

This work showed the process of thinking and employed standardised symbols to communicate the story. It presented me with an opportunity to review part-whole aspects within numbers and to explore division and multiplication, and to begin to lay the foundations of the idea of their inverse qualities.

Chicken hunt

This was an activity that arose from garden play, and a child whose family had recently acquired chickens. I told children the true story of how a Year 1 child's chickens had been attacked by a fox. Using props, I developed a narrative that showed some of the original quantity of chickens being eaten. Learners were then asked to find their own small chickens that I had hidden around our classroom and return to tell, and then record, their own stories.

The first sample shows an emergent number sentence incorporating a subtraction symbol to explain the operation. The drawing and the discussion during the picture's evolution was animated and assertive and the absolute priority to be communicated for the reader was for us to understand which chicken was eaten.

An arrow was drawn to explain this, using what Carruthers and Worthington have described as 'narrative action' which they suggest 'appears to support internalized mental images of earlier concrete operations of addition or subtraction calculations: the hand or arrows they include allow them to reflect on the operation and its function' (Carruthers & Worthington, 2008).

I prompted for the number sentence to accompany this story. No reference was made to numerals on the table or around the classroom and “3 - 1 2” (reversing the 2) was written confidently and with independence. The number sentence was said out loud and during the process of recording was acted out using fingers and Makaton to sign 'take away'. This work provides an example of a child successfully bridging their own knowledge of informal and formal symbolic representation for the calculation 3 - 1.

The next example was created by a child who also acted out the number sentence using Makaton for both the '-', and '=' symbols before recording them. A personal priority was given to explaining which chicken was eaten, shown with an 'x' and during a discussion group the author contradicted a friend who pointed to the chicken nearest the fox to explain one had been eaten from a group of five. This detail records the involvement of this child in the story-telling aspect of this activity. Both the picture and the number sentence held an equal importance and this was revealed when they spoke about their work.

The third recording shows the work of a number novice. However, their story was approached confidently and with interest and the recording was quickly completed and then explained to me and another child. Each horizontal line between the 5 and the 0 represented the action of a chicken being taken by the fox. During this discussion the child realised that they had only drawn 4 lines and added 1 more before their work was considered to be complete. This representation reveals an early understanding of subtraction and a generalisation of a standard symbol, adapted for personal expression in an emergent style. While recording, this child did not count down to subtract but counted up from one as they crossed out each chicken to be taken away.

The Chicken Hunt examples provide clear evidence of children understanding subtraction, in that they generated a number-story that started off with one quantity, some components were removed which reduced the final quantity of the group. Carruthers and Worthington suggest:

'It is important that children are free to work out their own sense of calculations in ways they understand' (2008).

Mathematical graphics support 'young children's thinking when they are encouraged to use their own ways of representing their personal mathematical meanings' (Worthington, 2007).

I observed that children at the cusp of understanding standardised symbols continued to use personalised methods of recording, when given a choice, for significantly longer than I would initially have anticipated. I also observed that most children at the end of their Reception year used a mixture of number sentences and pictographic recording to communicate their ideas, and that the two methods were used in conjunction with each other to consolidate and explain events.

The project offered a heightened mathematical environment which maintained a playful learning context, with an emphasis on graphical representations as a key feature for the learning progress. Graphical representations were used to stimulate number and calculating discussions, to develop metacognition and as opportunities to link existing knowledge with new ideas and standard written symbols. This approach allowed children to manoeuvre between standardised symbols and personal meanings.

References

Carruthers, E. and Worthington, M. (2008) 'Children's mathematical graphics: young children calculating for meaning', in Thompson, I. (Ed.) Teaching and learning early number, Berkshire: Open University Press (2nd edition)

Davis, G. and Pepper, K. (1992) 'Mathematical Problem Solving by Pre-School Children', Educational Studies in Mathematics, Vol: 23, No:4 August, 397-415

Early Years Foundation Stage (2012) DfEE

Gifford, S. (1997) 'When should they start doing sums? A critical consideration of the 'emergent mathematics' approach', in Thompson, E. (Ed.) Teaching and learning early number, Buckingham: Open University Press

Hughes, M. (1986) Children and Number: Difficulties in Learning Mathematics, Oxford: Blackwell

Worthington, M. and Carruthers, E. (2003) Children's Mathematics: Making Marks, Making Meaning, London: Paul Chapman Publishing

Worthington, M. (2007) 'Multi-modality, play and children's mark-making in maths', in Moyles, J. (Ed.) Early Years Foundations: Meeting the Challenge, Berkshire: Open University Press

If you enjoyed reading this article, you may like to consider purchasing the Young Children Learning Mathematics book, published by the Association of Teachers of Mathematics.