Skip over navigation

Or search by topic

Number and algebra

Geometry and measure

Probability and statistics

Working mathematically

Advanced mathematics

For younger learners

Four Circles

Age 14 to 16

ShortChallenge Level

- Problem

- Solutions

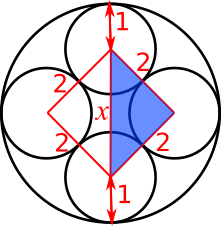

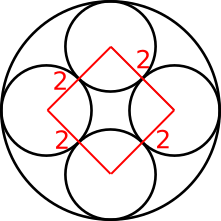

Using a square to draw a right-angled triangle

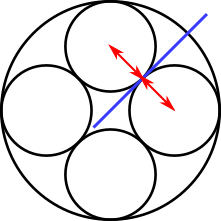

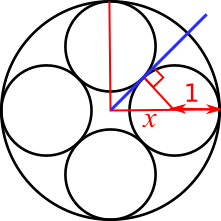

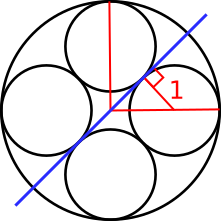

The blue line on the diagram below is a tangent to two of the small circles where they touch, so it is perpendicular to both of the radii shown in red.

That means that the two radii must make a straight line, so there is a straight line of length 2 which connects the centres of the two circles.

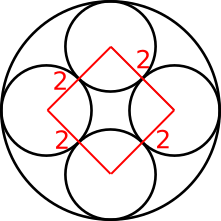

Drawing all of these lines on gives the square shown below (it must be a square not a rhombus because the diagram is symmetrical).

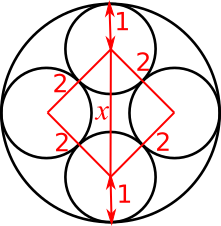

The vertical diagonal of the square, labelled $x$ below, will go through the centre of the larger circle, and the vertical distances from the centres of the small circles to the circumference of the larger circle will be 1, because the radii of the smaller circles are 1. This means that the diameter of the larger circle is $x$ + 2, as shown below.

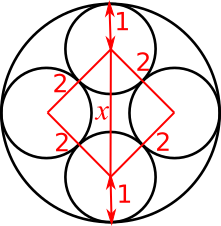

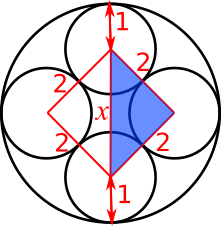

Since all of the angles in the square are right angles, $x$ is the hypotenuse of the right-angled triangle shown in blue below, where the other side lengths are both 2.

So, by Pythagoras' theorem, $$\begin{align}2^2+2^2&=x^2\\

4+4&=x^2\\

8&=x^2\\

x&=\sqrt{8}=2\sqrt{2}\end{align}$$

So the diameter of the larger circle is $x+2=2\sqrt{2}+2$ (or $\sqrt{8}+2$), so the radius of the larger circle is $\frac{1}{2}\left(2+2\sqrt{2}\right)=1+\sqrt2$ (or $\frac{1}{2}\left(2+\sqrt8\right)$).

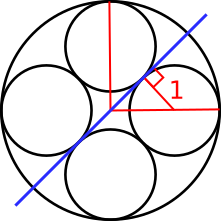

Using a tangent to draw a right-angled triangle

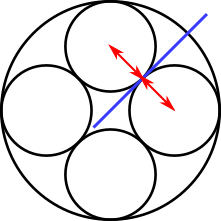

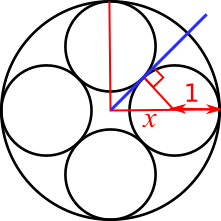

The blue line shown on the diagram is a tangent to the two top right smaller circles where they touch, so it is perpendicular to the radius shown. It also goes through the centre of the larger circle, as it is also tangent to the other pair of smaller circles where they touch, by the symmetry of the diagram. The red lines are drawn from the centre to the circumference of the larger circle so that they go through the centres of the smaller circles.

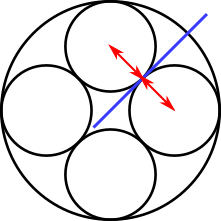

The angle between the two red lines is 90$^{\text{o}}$, because the diagram is symmetrical.

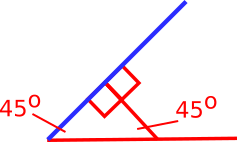

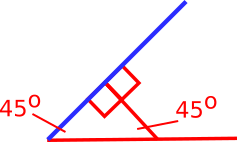

The blue line must make the same angle with each red line, because of the symmetry of the diagram. So it must make a 45$^{\text{o}}$ angle with each if the lines. This is shown in the diagram below, where the other angle in the triangle is also 45$^{\text{o}}$, because the angles in a triangle add up to 180$^{\text{o}}$.

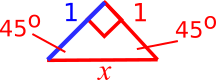

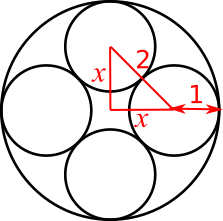

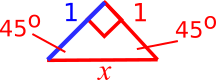

Since two angles are the same, the triangle must be isosceles, so the blue side must also be 1 (same as the red side which has length 1 because it is the radius of the smaller circle), as shown below.

So we can find $x$ using Pythagoras' theorem, and then $x+1$ will be the radius of the larger circle, which is shown in the diagram below.

By Pythagoras' theorem, $1^2+1^2=x^2$, so $x^2=2$, so $x=\sqrt2$. So the radius of the larger circle is $\sqrt2+1$.

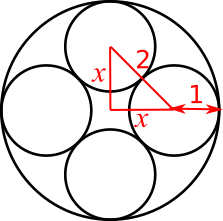

Using the centres of the circles to draw a right-angled triangle

The blue line on the diagram below is a tangent to two of the small circles where they touch, so it is perpendicular to both of the radii shown in red.

That means that the two radii must make a straight line, so there is a straight line of length 2 which connects the centres of the two circles.

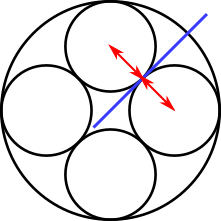

The other red lines in the diagram below join the centres of the small circles to the centres of the larger circle. The angle betwen them must be a right angle because the diagram is symmetrical.

So the radius of the larger circle must be $x+1$, and there is a right-angled triangle with sides $x$, $x$ and $2$.

By Pythagoras' theorem, $$\begin{align}x^2+x^2&=2^2 \\

2x^2&=4\\

x^2&=2\\

x&=\sqrt{2}\end{align}$$

So the radius of the larger circle is $x+1=\sqrt2+1$.

The blue line on the diagram below is a tangent to two of the small circles where they touch, so it is perpendicular to both of the radii shown in red.

That means that the two radii must make a straight line, so there is a straight line of length 2 which connects the centres of the two circles.

Drawing all of these lines on gives the square shown below (it must be a square not a rhombus because the diagram is symmetrical).

The vertical diagonal of the square, labelled $x$ below, will go through the centre of the larger circle, and the vertical distances from the centres of the small circles to the circumference of the larger circle will be 1, because the radii of the smaller circles are 1. This means that the diameter of the larger circle is $x$ + 2, as shown below.

Since all of the angles in the square are right angles, $x$ is the hypotenuse of the right-angled triangle shown in blue below, where the other side lengths are both 2.

So, by Pythagoras' theorem, $$\begin{align}2^2+2^2&=x^2\\

4+4&=x^2\\

8&=x^2\\

x&=\sqrt{8}=2\sqrt{2}\end{align}$$

So the diameter of the larger circle is $x+2=2\sqrt{2}+2$ (or $\sqrt{8}+2$), so the radius of the larger circle is $\frac{1}{2}\left(2+2\sqrt{2}\right)=1+\sqrt2$ (or $\frac{1}{2}\left(2+\sqrt8\right)$).

Using a tangent to draw a right-angled triangle

The blue line shown on the diagram is a tangent to the two top right smaller circles where they touch, so it is perpendicular to the radius shown. It also goes through the centre of the larger circle, as it is also tangent to the other pair of smaller circles where they touch, by the symmetry of the diagram. The red lines are drawn from the centre to the circumference of the larger circle so that they go through the centres of the smaller circles.

The angle between the two red lines is 90$^{\text{o}}$, because the diagram is symmetrical.

The blue line must make the same angle with each red line, because of the symmetry of the diagram. So it must make a 45$^{\text{o}}$ angle with each if the lines. This is shown in the diagram below, where the other angle in the triangle is also 45$^{\text{o}}$, because the angles in a triangle add up to 180$^{\text{o}}$.

Since two angles are the same, the triangle must be isosceles, so the blue side must also be 1 (same as the red side which has length 1 because it is the radius of the smaller circle), as shown below.

So we can find $x$ using Pythagoras' theorem, and then $x+1$ will be the radius of the larger circle, which is shown in the diagram below.

By Pythagoras' theorem, $1^2+1^2=x^2$, so $x^2=2$, so $x=\sqrt2$. So the radius of the larger circle is $\sqrt2+1$.

Using the centres of the circles to draw a right-angled triangle

The blue line on the diagram below is a tangent to two of the small circles where they touch, so it is perpendicular to both of the radii shown in red.

That means that the two radii must make a straight line, so there is a straight line of length 2 which connects the centres of the two circles.

The other red lines in the diagram below join the centres of the small circles to the centres of the larger circle. The angle betwen them must be a right angle because the diagram is symmetrical.

So the radius of the larger circle must be $x+1$, and there is a right-angled triangle with sides $x$, $x$ and $2$.

By Pythagoras' theorem, $$\begin{align}x^2+x^2&=2^2 \\

2x^2&=4\\

x^2&=2\\

x&=\sqrt{2}\end{align}$$

So the radius of the larger circle is $x+1=\sqrt2+1$.

You can find more short problems, arranged by curriculum topic, in our short problems collection.

You may also like

Ladder and Cube

A 1 metre cube has one face on the ground and one face against a wall. A 4 metre ladder leans against the wall and just touches the cube. How high is the top of the ladder above the ground?

Bendy Quad

Four rods are hinged at their ends to form a convex quadrilateral. Investigate the different shapes that the quadrilateral can take. Be patient this problem may be slow to load.