Or search by topic

Number and algebra

Geometry and measure

Probability and statistics

Working mathematically

Advanced mathematics

For younger learners

The Converse of Pythagoras

Pythagoras' theorem states that:

"If a triangle with sides $a, b, c$ has a right-angle, and $c$ is the hypotenuse, then $a^2+b^2=c^2$."

You can find some proofs of Pythagoras' theorem here and here. For this problem you can assume that Pythagoras' theorem is true.

The converse of Pythagoras' theorem states that:

"If a triangle has lengths $a, b$ and $c$ which satisfy $a^2+b^2=c^2$ then it is a right-angled triangle."

We can prove this by using a proof by contradiction, which means starting by assuming that the opposite is true and then showing that this leads to an inconsistency or contradiction.

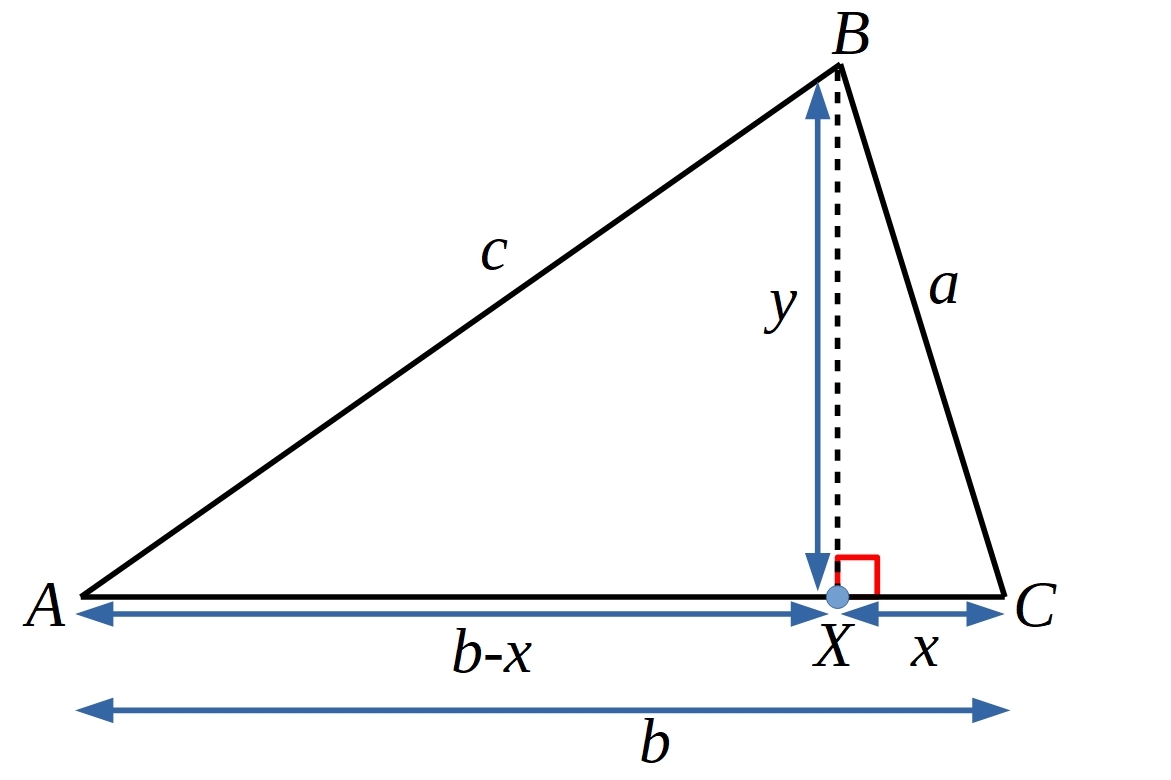

Below is a proof sorter of a proof that if $a^2+b^2=c^2$ then $C$ cannot be less than $90^{\circ}$, and a diagram to accompany the proof. Can you use the diagram and the statements to reconstruct a proof that angle $C$ cannot be less than $90^{\circ}$?

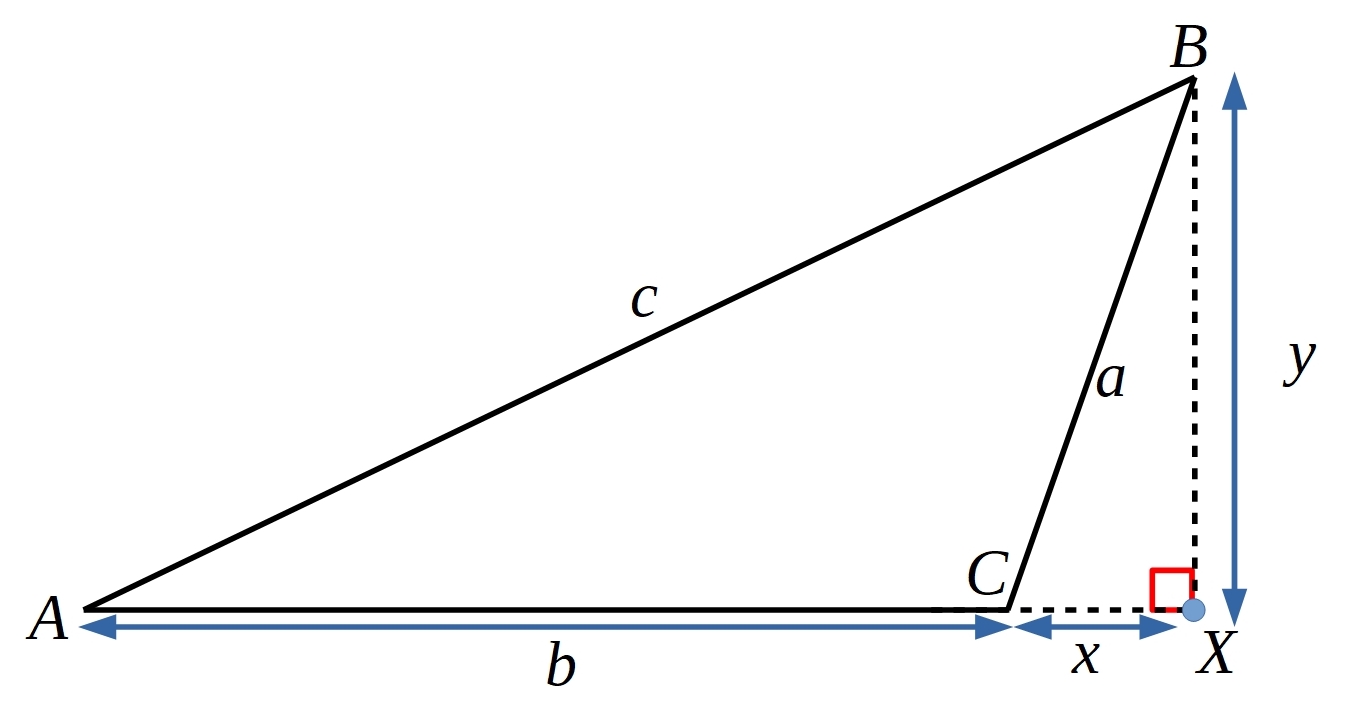

Can you use the diagram below, and the ideas from the proof sorter above, to construct a proof that angle $C$ cannot be more than $90^{\circ}$?

Once both proofs have been completed then we know that $C$ cannot be less than $90^{\circ}$, and that $C$ cannot be more than $90^{\circ}$, therefore $C$ must be equal to $90^{\circ}$ and hence if we have $a^2+b^2=c^2$ then the triangle is right-angled at $C$.