Skip over navigation

First we need to find how many discs we can stack $1 \ \mathrm{m}$ in the $y$-direction, the centres of all the discs lie on a line at 60 degrees to the horizontal.

The total number stacked vertically $= \frac{1}{d\sin 60^\circ}$ (where $d$ is the diameter of a disc measured in m)

Case 1: $d = 10 \ \mathrm{cm} =0.1 \ \mathrm{m}$

$\textrm{Number of discs stacked vertically} = 11 $

$\textrm{Total number of discs} = (6 \times 10) + (5 \times 9) = 105 $

$\textrm{Packing fraction} = \frac{\textrm{No. Discs} \times \pi r^2}{1} = 0.825 $

Case 2: d=1cm = 0.01m

Number of discs stacked vertically = 115

Total number of discs = (58x100) + (57x99)= 11443

Packing fraction =$\frac{No. Discs x \pi r^2}{1}$= 0.899

Case 3: d = 1mm =0.001m

Number of discs stacked vertically = 1154

Total number of discs = (577x1000) + (577x999)= 1153423

Packing fraction =$\frac{No. Discs x \pi r^2}{1}$= 0.906

Extension

The most efficent method of packing spheres is face centred cubic packing, FCC packing will provide us with an upper limit to the number of spheres we can pack.

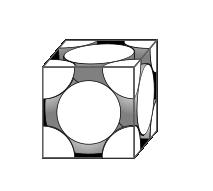

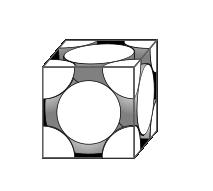

In the Face Centered Cubic (FCC) unit cell there is one host sphere at each corner and one host sphere in each face. Since each corner sphere contributes one eighth of its volume to the cell interior, and each face sphere contributes one half of its volume to the cell interior (and there are six faces), then there are a total of $\frac{1}{8}x8 + \frac{1}{2} x 6 = 4$ spheres in the unit cell.

If we define

a = length of one side of the unit cell

r = radius of one sphere

we can see that 4rsin(45) = a.

The volume fraction of such a unit cell is the number of spheres in the cell multiplied by the volume of a sphere and then divided by volume of cube.

Volume fraction = $\frac{4x \frac{4}{3}\pi r^3}{(2\sqrt(2)r)^3}$ = 0.74

The number of spheres in a volume of $1m^3$ is therefore:

$\frac{0.74}{\frac{4}{3}\pi (0.005)^3}= 1413295$

This is the upper limit to the number of spheres we may pack. It is likely we will not actually be able to pack quite so many. If we did adopt this method we would have fractions of spheres along the sides of the container, as shown in the unit cell above.

Or search by topic

Number and algebra

Geometry and measure

Probability and statistics

Working mathematically

Advanced mathematics

For younger learners

Efficient Packing

Age 14 to 16

Challenge Level

- Problem

- Student Solutions

- Teachers' Resources

First we need to find how many discs we can stack $1 \ \mathrm{m}$ in the $y$-direction, the centres of all the discs lie on a line at 60 degrees to the horizontal.

The total number stacked vertically $= \frac{1}{d\sin 60^\circ}$ (where $d$ is the diameter of a disc measured in m)

Case 1: $d = 10 \ \mathrm{cm} =0.1 \ \mathrm{m}$

$\textrm{Number of discs stacked vertically} = 11 $

$\textrm{Total number of discs} = (6 \times 10) + (5 \times 9) = 105 $

$\textrm{Packing fraction} = \frac{\textrm{No. Discs} \times \pi r^2}{1} = 0.825 $

Case 2: d=1cm = 0.01m

Number of discs stacked vertically = 115

Total number of discs = (58x100) + (57x99)= 11443

Packing fraction =$\frac{No. Discs x \pi r^2}{1}$= 0.899

Case 3: d = 1mm =0.001m

Number of discs stacked vertically = 1154

Total number of discs = (577x1000) + (577x999)= 1153423

Packing fraction =$\frac{No. Discs x \pi r^2}{1}$= 0.906

Extension

The most efficent method of packing spheres is face centred cubic packing, FCC packing will provide us with an upper limit to the number of spheres we can pack.

In the Face Centered Cubic (FCC) unit cell there is one host sphere at each corner and one host sphere in each face. Since each corner sphere contributes one eighth of its volume to the cell interior, and each face sphere contributes one half of its volume to the cell interior (and there are six faces), then there are a total of $\frac{1}{8}x8 + \frac{1}{2} x 6 = 4$ spheres in the unit cell.

If we define

a = length of one side of the unit cell

r = radius of one sphere

we can see that 4rsin(45) = a.

The volume fraction of such a unit cell is the number of spheres in the cell multiplied by the volume of a sphere and then divided by volume of cube.

Volume fraction = $\frac{4x \frac{4}{3}\pi r^3}{(2\sqrt(2)r)^3}$ = 0.74

The number of spheres in a volume of $1m^3$ is therefore:

$\frac{0.74}{\frac{4}{3}\pi (0.005)^3}= 1413295$

This is the upper limit to the number of spheres we may pack. It is likely we will not actually be able to pack quite so many. If we did adopt this method we would have fractions of spheres along the sides of the container, as shown in the unit cell above.

You may also like

Some(?) of the Parts

A circle touches the lines OA, OB and AB where OA and OB are perpendicular. Show that the diameter of the circle is equal to the perimeter of the triangle

Polycircles

Show that for any triangle it is always possible to construct 3 touching circles with centres at the vertices. Is it possible to construct touching circles centred at the vertices of any polygon?

Circumspection

M is any point on the line AB. Squares of side length AM and MB are constructed and their circumcircles intersect at P (and M). Prove that the lines AD and BE produced pass through P.