Or search by topic

Number and algebra

Geometry and measure

Probability and statistics

Working mathematically

Advanced mathematics

For younger learners

Pythagoras Proofs

- Problem

- Getting Started

- Student Solutions

- Teachers' Resources

Method 1

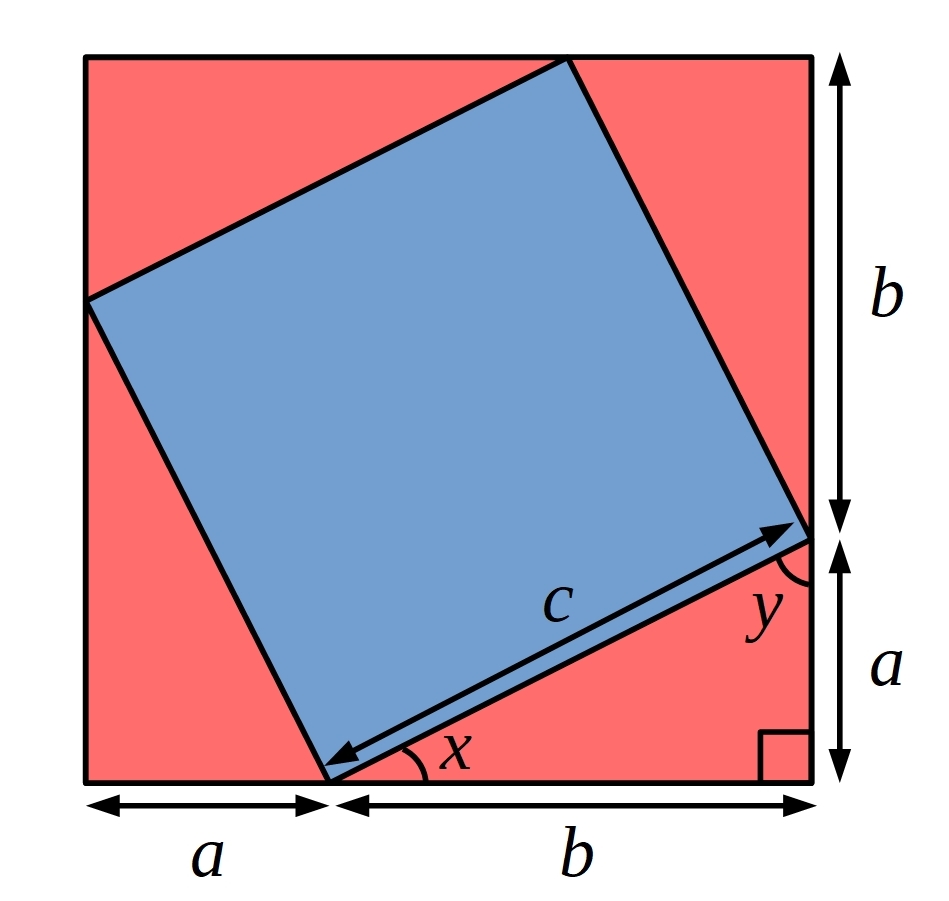

Boyi from Wellington in Malaysia, Fiona from Wellington College International Shanghai in China and Lewis from Wilson's School in the UK used the picture below and the proof sorter to create a proof of Pythagoras' theorem. Fiona wrote:

This proof is shown by making a square that has $c$ length on each side, putting 4 identical triangles around the square, forming a bigger square. We then can know that the four triangles’ area adds together to form the square in the middle, which is $c^2.$ Therefore, the area of the enclosed square = the area of large square – area of the four triangles.

The area of the large square is: $(a+b)^2=a^2+2ab+b^2,$ and the area of the four triangles is: $4\times\frac12\times ab=2ab.$

Then we can know that the area of the enclosed square is: $a^2+2ab+b^2-2ab=a^2+b^2.$ The area of the enclosed square is also given by $c^2,$ therefore $a^2+b^2=c^2.$

There is one piece of information that is missing from Fiona's proof. It is not clear that, starting from the small blue square, when you add four triangles, you get a square (and not some other shape). In particular, Fiona's proof is missing the fact that the 'sides' of the 'bigger square' are straight lines.

Lewis used this diagram to demonstrate this idea (along with the information that, since they are the angles in a right angled triangle, $x+y=90^\circ$):

Method 2

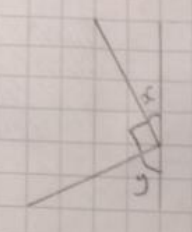

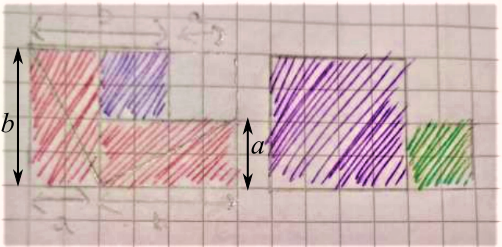

Boyi, Fiona and Lewis used the picture below to come up with another proof of Pythagoras' theorem. Fiona's proof is below the diagram.

First, the area of the first square is given by $(a+b)^2$ or $4\left(\frac12 ab\right) + c^2.$

The area of the second square is given by $(a+b)^2$ or $4\left(\frac12 ab\right) + a^2 + b^2.$

Since the squares have equal areas we can set them equal to another and subtract equals. $4\left(\frac12 ab\right) + a^2 + b^2 = 4\left(\frac12 ab\right) + c^2$

Subtracting equals from both sides we have $a^2+b^2=c^2,$ which proves the Pythagoras theory.

Method 3:

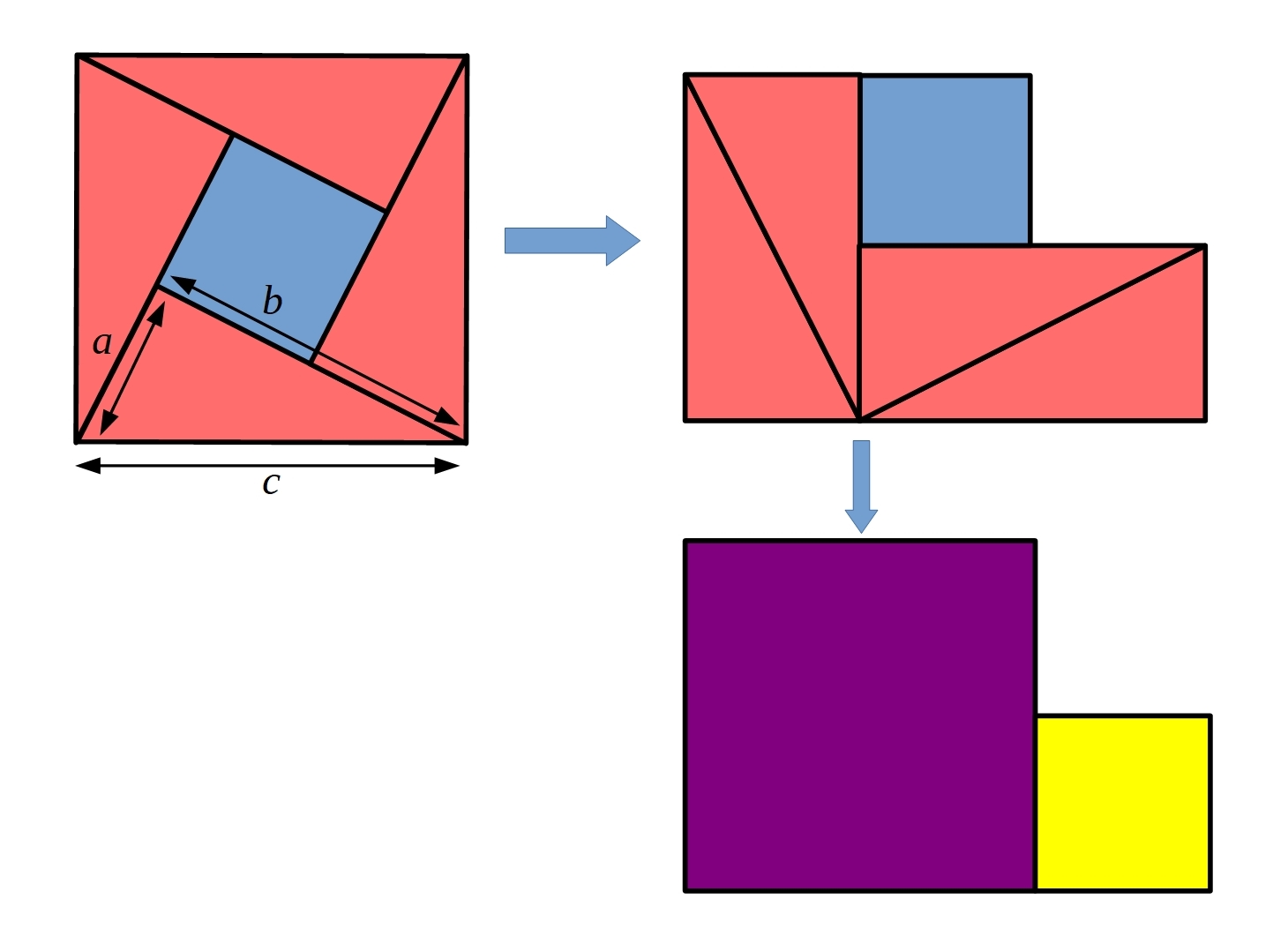

Some people tried to use this picture to create a third proof of Pythagoras' theorem, but wrote that the side length of the blue square was $a.$

This is Boyi's proof, which doesn't use the third diagram at all:

This is Fiona's proof, with a diagram from Lewis's proof added. Two more lengths have been drawn on to Lewis's diagram, for clarity.

The first square has an area of $c^2,$ and we can look the second shape as two squares – One small square (on the right) and one big square (on the left), shown on the last shape.

Then, this shows $a^2+b^2,$ and we can see that the two area are equal, so $a^b+b^2=c^2.$

Method 4

Another method of proving Pythagoras' Theorem can be found in the problem "A Matter of Scale".

Well done to Andrew from Island School, who demonstrated how this works.

Fiona sent in some opinions about which proof was most convincing and which was easiest to understand:

Which proof is the most “convincing”? – In my opinion, I think that second one is the most “convincing” because it uses a lot of math equations to show the proof.

Which proof is easier to understand? – I think that the last one is the most interesting and easy to understand because it basically uses shapes to illustrate The Pythagoras theorem.

You may also like

Adding All Nine

Make a set of numbers that use all the digits from 1 to 9, once and once only. Add them up. The result is divisible by 9. Add each of the digits in the new number. What is their sum? Now try some other possibilities for yourself!

Doodles

Draw a 'doodle' - a closed intersecting curve drawn without taking pencil from paper. What can you prove about the intersections?