Or search by topic

Number and algebra

Geometry and measure

Probability and statistics

Working mathematically

Advanced mathematics

For younger learners

Published 2009 Revised 2013

What's All the Talking About?

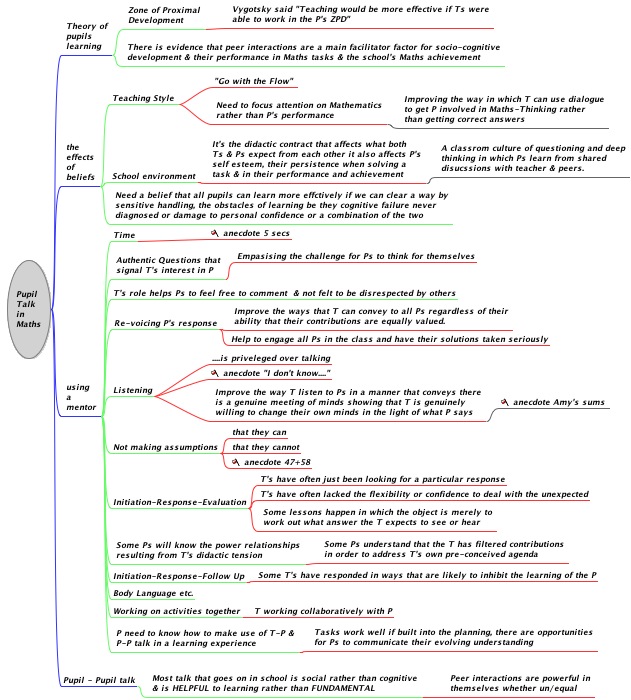

Here's a picture of thoughts and ideas relating to teacher-pupil talk and pupil-pupil talk in the classroom. Practical ideas for improving the mathematics in a school, by considering the interactions between teachers and pupils, are considered along with some thoughts about how teacher-pupil talk can affect the pupils themselves.

Want to see it more easily and print it out? Go here.

Lots of the time that a teacher spends with children is spent trying to engage with them, to ensure the best possibility for their mathematical development. in this article I encourage you to get involved in the conversational side of mathematics and in different forms of communication and presentation.

Let's look at what may be involved in trying to improve the quality of pupil-teacher and pupil-pupil talk in mathematics.

I ran a course on "Pupil - Teacher Talk in the Maths Lesson" which, some time later, was followed up as I worked alongside the teachers in their classrooms. On one occasion a teacher went up to a boy called Michael; here's the conversation:

So it went on, with Michael not saying a word. The teacher then came over to me and said "I've had a most interesting conversation with Michael." Then there was a slight pause as if she were going to tell me more but I jumped in and asked, "Did he actually say anything?"

A slight pause followed by an embarrassed teacher and then: "Oh !. . . . . No!"

At least she was trying to talk with the individual pupil and said that she wanted to know how he had done his work. But somehow what she said probably did not reflect what she really thought about her pupils' learning and her teaching. It's rather like the situation when a teacher initiates some talk by asking a question. The pupils give a response in the form of an answer and then the teacher

replies with a follow up question. On other occasions the teacher will simply evaluate the pupil's answer - "Good", "Well done!", "Right", "OK", "No!", "Think again" or "Is that the best you can do!". The last example does not expect a reply.

There is some inequality in the power structure of this "talk". This is sometimes accompanied by a "game-type" situation in which the purpose of the lesson seems to be "try to guess what the teacher is thinking". I believe this sometimes happens because the teacher is at that time lacking the flexibility or confidence to deal with the unexpected. This may be because of the teacher's belief about

how pupils learn. Some of the more mature pupils will be aware that the teacher has filtered pupils' contributions in order to address the teacher's own pre-conceived agenda. Research suggests that this kind of inequality in the power structure during "pupil-teacher talk" inhibits the future learning of the pupil. And of course other factors are involved in communication too, such as the

teacher's body language, and the environment they create.

So, how can the situation be improved so that better learning takes place? I have come to see that one of the biggest influences on teacher behaviour is the teacher's beliefs regarding learning.

I seem to have developed these kinds of beliefs, without the research. Many teachers will, as I have done, develop beliefs through reflecting on what they have experienced in the classroom and teacher meetings. Some teachers will be encouraged by the work of Vygotsky. When writing about the Zone of Proximal Development [ZPD] he says that it is his belief that teaching is more effective when

children work in the ZPD, the difference between what a learner can do without help and what he or she can do with help. Teacher scaffolding is therefore very important - and can be done in many ways.

For example, if you're lucky enough to be observing a maths lesson, watch how the teacher responds to ideas that pupils put forward when they are working on a task. Consider a situation where a group of pupils are working on a spatial task. One child suggests, in a self-questioning way,

"Its something like a cube. . . . ."

The teacher can helpfully follow that in a number of ways. Re-voicing precisely what the pupil said to the group in a questioning voice.

Teacher "It's something like a cube (?). . ."

This encourages other pupils to comment on that idea, ie encourages pupil-pupil talk to emerge.

These peer interactions are a powerful source of learning, not only between children of similar ability. It's been found to be true when the pupils' knowledge is unequal, more able pupils working with others of lesser ability. It's important to convey to all pupils, regardless of their ability, that their contributions are equally valued so that they can engage in the conversations and have their

suggestions taken seriously.

When the teacher is sensitive to these kinds of interactions this can create a classroom culture of questioning and deeper thinking, in which pupils learn from shared discussion with the teacher and peers. Teachers focus their attention on the mathematics rather than the pupils' performance. They use dialogue to get pupils involved in mathematical thinking rather than getting the correct

answers.

Teachers see improvements when their own listening improves and they really listen to what a pupil is saying. I was with a group of able pupils, aged 11, on a residential course and the pupils were sharing experiences that they felt arose particularly because they were more able. One young boy related how earlier that week he had some work that he could not do. He went to the teacher, sitting

at her desk at the front and said "I don't know how to do this." Then she quickly replied saying,"Yes you do, because you are clever!"

I then asked him,"How did you feel at the point?"and he replied "I felt I was like a wall of glass. She didn't really see me at all!'"

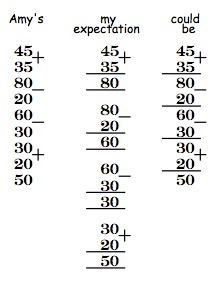

I would imagine that the teacher thought she had done the right thing in confirming that he was clever. But she had unfortunately also shown that she did not listen and that seemed to hurt him more. When listening well to our pupils it's important to convey a genuine interest; on some occasions it may be necessary to change our minds in the light of what the pupil says or records. I was working

with an 8 year old who was doing a problem that involved a number of additions and subtraction. Here are three versions: what I saw on her paper, what I was expecting and an in-between alternative.

If you are interested in researching further then Google 'Teacher Interaction with pupils', 'Pupil-Teacher talk' or 'Teacher-Pupil dialogue'. You can also search at bsrlm.org.uk

If this is new to you then please give it some thought, and speak to others about it. Your pupils deserve it!