Skip over navigation

Article by Dr Sue Gifford University of Roehampton

The first article Mathematical Problem Solving in the Early Years pointed out that young children are natural problem setters and solvers: that is how they learn. This article suggests ways to develop children's problem solving strategies and confidence. Problem solving is an important way of learning, because it motivates children to connect previous knowledge with new situations and to develop flexibility and creativity in the process. Therefore it is important that children see themselves as successful problem solvers who relish a challenge and can persist when things get tricky.

What does mathematical problem solving look like for three to five year olds?

Problems are essentially things you do not know how to solve. If children know or are told the method to use, then they are not problem solving: therefore one child's problem is another child's routine exercise. This means that in the early years, even very simple activities may be a problem for one child but not another: more interesting problems involve alternative solutions using different mathematical ideas. When laying a table, a child could either get plates one at a time, or they could count the chairs then the plates, or they could just make sure they have more plates than chairs and tell everyone to help themselves! These strategies involve diverse aspects of mathematics, such as one-to-one correspondence, counting and cardinality, or estimation and number comparison. Reviewing and discussing these alternative solutions can help children learn about both mathematics and problem solving.

Quality provision in the early years encourages children to pose their own problems, with a range of possible solutions. For instance, with construction materials, children can decide to make a car for collaborative play, make houses for the three bears or make an abstract pattern. More flexible resources can

create more mathematical opportunities, prompting children to choose shapes according to their properties and to explore different combinations and arrangements. Sometimes it is hard to identify whether children are engaged in problem solving, but if you are aware of the potential mathematical learning in an activity, then observing children can reveal their decision making, such as when children

choose certain blocks before they start building or dismantle a construction and use a more efficient arrangement. Discussion with a child can help them to articulate why they chose certain shapes or changed their minds.

Quality provision in the early years encourages children to pose their own problems, with a range of possible solutions. For instance, with construction materials, children can decide to make a car for collaborative play, make houses for the three bears or make an abstract pattern. More flexible resources can

create more mathematical opportunities, prompting children to choose shapes according to their properties and to explore different combinations and arrangements. Sometimes it is hard to identify whether children are engaged in problem solving, but if you are aware of the potential mathematical learning in an activity, then observing children can reveal their decision making, such as when children

choose certain blocks before they start building or dismantle a construction and use a more efficient arrangement. Discussion with a child can help them to articulate why they chose certain shapes or changed their minds.

Creating opportunities for problem solving

If children do not set their own problems, then developing their problem solving strategies and confidence becomes an equal opportunities issue: teachers will need to find problems which engage children. Problem solving opportunities can be created by providing resources, by giving children responsibility within everyday routines and activities or by identifying issues for discussion sessions. Sometimes it is possible to opportunistically pose an appropriate challenge, like, 'What's the biggest arch you can make with the blocks?' or problem solving can be planned into routine situations, like sharing fruit or following a recipe.

Projects and stories offer opportunities for bigger problems, such as deciding by voting, redesigning an area, resolving a dilemma for story characters, or giving instructions for making a hat for a giant, and these can be the focus of group discussions. The issue is not so much who thought of it first, but whether the children engage with the problem and come to see it as their own. The art of problem posing involves presenting a situation as genuinely problematic for the adult or character involved: engaging children with blatant errors, muddles or injustices is one way of doing this, as with missing big trucks or an unfair distribution of pirate gold.

Planning for problem posing

According to Carr et al (1994) three things affect the level of difficulty for children: This implies that, in a familiar context with a clear purpose, such as sharing fruit, children will be able to deal creatively with more mathematically demanding challenges, perhaps involving remainders and fractions, but in an unfamiliar context they may only demonstrate basic skills. Carr et al (1994) also suggest

that children need to feel in control of the outcome, or they may just look for the right answer to please the teacher. Familiar contexts and purposes do not have to be 'real': young children will readily engage with toys' dilemmas and be outraged by pirate panda's selfishness in Maths Story Time. This

suggests that young children need problems:

This implies that, in a familiar context with a clear purpose, such as sharing fruit, children will be able to deal creatively with more mathematically demanding challenges, perhaps involving remainders and fractions, but in an unfamiliar context they may only demonstrate basic skills. Carr et al (1994) also suggest

that children need to feel in control of the outcome, or they may just look for the right answer to please the teacher. Familiar contexts and purposes do not have to be 'real': young children will readily engage with toys' dilemmas and be outraged by pirate panda's selfishness in Maths Story Time. This

suggests that young children need problems:

Educationally rich problems may have more than one solution and can be solved using a range of methods at different levels. The pirate panda activity in Maths Story Time is based on a 'redistribution' problem, where 12 biscuits are shared between two dolls, then another one comes along wanting a share (Davis & Pepper, 1992). Researchers found 26 different solutions among 45 pre-school children, suggesting they were not using learned methods, but instead were adapting what they knew. This was a genuine problem for most young children, as even 8 year olds had difficulty explaining their solutions. The main strategies used for redistribution were: Surprisingly, the quickest solution, of taking two from each, was used by some children who were not yet counting and would not have been considered mathematically proficient. The last strategy of crumbling the biscuits was not anticipated by researchers, who reluctantly acknowledged it was a successful solution

(and indicated some creative problem solving!). The researchers also concluded that some children were prompted by this problem to reveal an intuitive understanding of ratio, as they could just 'see' how to split six biscuits in the ratio 2:1; they also seemed to recognise that this would result in three equal numbers. This problem therefore engages children in a range of mathematical skills and

ideas, such as counting, subitising, comparing and recognising numerical relationships. It is an educationally useful problem because it can be tackled successfully by all children, whatever their mathematical proficiency, and gives experience of adapting a range of mathematical knowledge in the stages of problem solving, by devising a strategy and checking that a solution had been reached.

Surprisingly, the quickest solution, of taking two from each, was used by some children who were not yet counting and would not have been considered mathematically proficient. The last strategy of crumbling the biscuits was not anticipated by researchers, who reluctantly acknowledged it was a successful solution

(and indicated some creative problem solving!). The researchers also concluded that some children were prompted by this problem to reveal an intuitive understanding of ratio, as they could just 'see' how to split six biscuits in the ratio 2:1; they also seemed to recognise that this would result in three equal numbers. This problem therefore engages children in a range of mathematical skills and

ideas, such as counting, subitising, comparing and recognising numerical relationships. It is an educationally useful problem because it can be tackled successfully by all children, whatever their mathematical proficiency, and gives experience of adapting a range of mathematical knowledge in the stages of problem solving, by devising a strategy and checking that a solution had been reached.

Sharing problems are very useful because they are familiar and purposeful, and the level of difficulty can be easily adapted: for instance this problem can be simplified to just six biscuits; the pirate panda version in Mathematics Story Time includes more toys, and Pat Hutchins' story, 'The Doorbell Rang' (Using Books) is essentally the same problem with more biscuits and an ever increasing number of children. Variations can include remainders, such as 10 shared between three: it is interesting to see if children suggest solutions such as subtracting one (usually by eating the extra one) adding two more, or dividing into thirds. If children have relevant experience of fractions, even four year olds can tackle problems such as four biscuits shared between three, or seven shared between four (Anthony and Walshaw, 2007:181). Therefore sharing problems can involve a range of mathematics ideas, from 'same number' to fractions of wholes and numbers.

Problem-solving processes and strategies

As identified in Jennie Pennant's article, Developing Excellence in Problem Solving with Young Learners, the stages of problem solving include 'getting started', 'working on the problem', 'digging deeper' and 'reflecting'. Of course, some children may just rush towards a solution

without going through preliminary or reflective stages. Deloache and Brown (1987) observed the following levels of sophistication in approaches, with two to three year olds ordering nesting cups and four to seven year olds making a train-track circuit:

As identified in Jennie Pennant's article, Developing Excellence in Problem Solving with Young Learners, the stages of problem solving include 'getting started', 'working on the problem', 'digging deeper' and 'reflecting'. Of course, some children may just rush towards a solution

without going through preliminary or reflective stages. Deloache and Brown (1987) observed the following levels of sophistication in approaches, with two to three year olds ordering nesting cups and four to seven year olds making a train-track circuit:

Research suggests that mathematical problem solving processes look essentially the same at any age and young children employ similar strategies to older ones: it is experience rather than age which makes a difference, according to Askew and Wiliam (1995). At the different stages in the process, successful problem solvers' strategies include:

Supporting children's problem solving

Adults can therefore help children to be aware of processes and strategies, and to review their initial solution and consider alternatives. Burton (1984) suggested that children be taught to use 'self-organising questions' at the different stages. Examples for younger children might be:

Assessing problem solving: Characteristics of effective learning

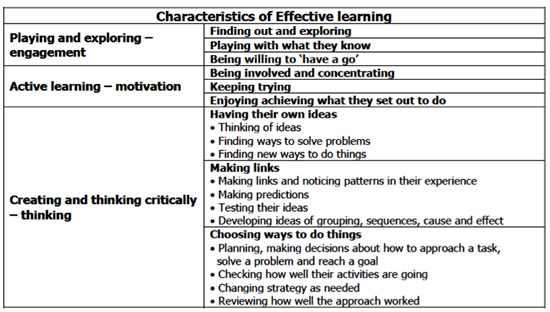

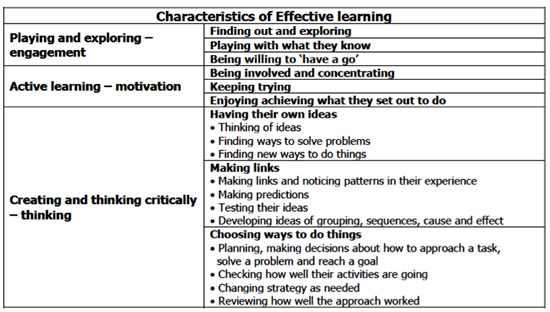

As well as demonstrating children's understanding and use of mathematical ideas, problem solving clearly allows children to demonstrate the EYFS 'Characteristics of effective learning' in mathematics (see the Early Years Foundation Stage Framework): it involves children in Playing and exploring, Active learning and Creating and thinking critically, as exemplified for inspectors of mathematics in the chart below (Ofsted, 2013). This includes aspects such as being willing to 'have a go' and noticing patterns, as well as making decisions about problem solving, including planning, checking, changing strategy and reviewing.

Most importantly, rich problems develop children's confidence and flexibility in using the mathematics knowledge they have to choose and create strategies, developing problem-solving skills for life.

Useful resources

Balances, Mud Kitchen, Building Towers, Making a Picture, Collecting

Routine activities

Tidying, Packing, Cooking, Playing Incey Wincey Spider

Discussion sessions

Shapes in the Bag, Number Rhymes, Maths Story Time, Using Books

NB: Other books for problem posing include: 'The Shopping Basket', 'The Great Pet Sale'

See also New Zealand government website 'Picture books with mathematical content'.

References

Anthony, G. & M. Walshaw (2007) Effective pedagogy in mathematics/pangarau:

best evidence synthesis (BES) Wellington, NZ: Ministry of Education p.181

http://educationcounts.edcentre.govt.nz/publications/curriculum/bes-eff-pedagogy.html

Askew, M. & D. Wiliam (1995). Recent research in mathematics education 5-

16. London, HMSO.

Burton, L. (1984). Thinking Things Through: Problem solving in mathematics. London, Basil Blackwell.

Carr, M., S. Peters, et al. (1994). Early childhood mathematics: Finding the right level of challenge. Mathematics education: a handbook for teachers. J. Neyland. Wellington, Wellington College of education. 1: 271-282.

Coltman, P., D. Petyaeva, et al. (2002). "Scaffolding learning through meaningful tasks and adult interaction." Early Years 22(1): 39-49.

Curtis, A. (1998). A curriculum for the pre-school child: learning to learn. London, Routledge.

Davis, G. & K. Pepper (1992). "Mathematical problem solving by pre-school children." Educational Studies in Mathematics 23: 397-415.

Deloache, J., S. & A. Brown, M. (1987). The early emergence of planning skills in children. The child's construction of the world. J. Bruner and H. Haste. London, Methuen: 108-130.

Gifford, S. (2005) Teaching mathematics 3-5: developing learning in the foundation stage Maidenhead: Open University Press/McGraw-Hill Education

Gura, P. (1992). Exploring learning: young children and blockplay. London, Paul

Chapman Publishing Ltd.

Office for Standards in Education. (2013). Mathematics in school inspection January 2013: Information pack for training. Retrieved from

https://www.whatdotheyknow.com/request/additional_guidance_for_inspecto

Or search by topic

Number and algebra

Geometry and measure

Probability and statistics

Working mathematically

Advanced mathematics

For younger learners

Age 3 to 7

Published 2016 Revised 2019

Mathematical Problem Solving in the Early Years: Developing Opportunities, Strategies and Confidence

The first article Mathematical Problem Solving in the Early Years pointed out that young children are natural problem setters and solvers: that is how they learn. This article suggests ways to develop children's problem solving strategies and confidence. Problem solving is an important way of learning, because it motivates children to connect previous knowledge with new situations and to develop flexibility and creativity in the process. Therefore it is important that children see themselves as successful problem solvers who relish a challenge and can persist when things get tricky.

What does mathematical problem solving look like for three to five year olds?

Problems are essentially things you do not know how to solve. If children know or are told the method to use, then they are not problem solving: therefore one child's problem is another child's routine exercise. This means that in the early years, even very simple activities may be a problem for one child but not another: more interesting problems involve alternative solutions using different mathematical ideas. When laying a table, a child could either get plates one at a time, or they could count the chairs then the plates, or they could just make sure they have more plates than chairs and tell everyone to help themselves! These strategies involve diverse aspects of mathematics, such as one-to-one correspondence, counting and cardinality, or estimation and number comparison. Reviewing and discussing these alternative solutions can help children learn about both mathematics and problem solving.

Quality provision in the early years encourages children to pose their own problems, with a range of possible solutions. For instance, with construction materials, children can decide to make a car for collaborative play, make houses for the three bears or make an abstract pattern. More flexible resources can

create more mathematical opportunities, prompting children to choose shapes according to their properties and to explore different combinations and arrangements. Sometimes it is hard to identify whether children are engaged in problem solving, but if you are aware of the potential mathematical learning in an activity, then observing children can reveal their decision making, such as when children

choose certain blocks before they start building or dismantle a construction and use a more efficient arrangement. Discussion with a child can help them to articulate why they chose certain shapes or changed their minds.

Quality provision in the early years encourages children to pose their own problems, with a range of possible solutions. For instance, with construction materials, children can decide to make a car for collaborative play, make houses for the three bears or make an abstract pattern. More flexible resources can

create more mathematical opportunities, prompting children to choose shapes according to their properties and to explore different combinations and arrangements. Sometimes it is hard to identify whether children are engaged in problem solving, but if you are aware of the potential mathematical learning in an activity, then observing children can reveal their decision making, such as when children

choose certain blocks before they start building or dismantle a construction and use a more efficient arrangement. Discussion with a child can help them to articulate why they chose certain shapes or changed their minds.Creating opportunities for problem solving

If children do not set their own problems, then developing their problem solving strategies and confidence becomes an equal opportunities issue: teachers will need to find problems which engage children. Problem solving opportunities can be created by providing resources, by giving children responsibility within everyday routines and activities or by identifying issues for discussion sessions. Sometimes it is possible to opportunistically pose an appropriate challenge, like, 'What's the biggest arch you can make with the blocks?' or problem solving can be planned into routine situations, like sharing fruit or following a recipe.

Projects and stories offer opportunities for bigger problems, such as deciding by voting, redesigning an area, resolving a dilemma for story characters, or giving instructions for making a hat for a giant, and these can be the focus of group discussions. The issue is not so much who thought of it first, but whether the children engage with the problem and come to see it as their own. The art of problem posing involves presenting a situation as genuinely problematic for the adult or character involved: engaging children with blatant errors, muddles or injustices is one way of doing this, as with missing big trucks or an unfair distribution of pirate gold.

Planning for problem posing

According to Carr et al (1994) three things affect the level of difficulty for children:

- familiar contexts

- meaningful purposes

- mathematical complexity.

This implies that, in a familiar context with a clear purpose, such as sharing fruit, children will be able to deal creatively with more mathematically demanding challenges, perhaps involving remainders and fractions, but in an unfamiliar context they may only demonstrate basic skills. Carr et al (1994) also suggest

that children need to feel in control of the outcome, or they may just look for the right answer to please the teacher. Familiar contexts and purposes do not have to be 'real': young children will readily engage with toys' dilemmas and be outraged by pirate panda's selfishness in Maths Story Time. This

suggests that young children need problems:

This implies that, in a familiar context with a clear purpose, such as sharing fruit, children will be able to deal creatively with more mathematically demanding challenges, perhaps involving remainders and fractions, but in an unfamiliar context they may only demonstrate basic skills. Carr et al (1994) also suggest

that children need to feel in control of the outcome, or they may just look for the right answer to please the teacher. Familiar contexts and purposes do not have to be 'real': young children will readily engage with toys' dilemmas and be outraged by pirate panda's selfishness in Maths Story Time. This

suggests that young children need problems:

- which they understand - in familiar contexts,

- where the outcomes matter to them - even if imaginary,

- where they have control of the process,

- involving mathematics with which they are confident.

Educationally rich problems may have more than one solution and can be solved using a range of methods at different levels. The pirate panda activity in Maths Story Time is based on a 'redistribution' problem, where 12 biscuits are shared between two dolls, then another one comes along wanting a share (Davis & Pepper, 1992). Researchers found 26 different solutions among 45 pre-school children, suggesting they were not using learned methods, but instead were adapting what they knew. This was a genuine problem for most young children, as even 8 year olds had difficulty explaining their solutions. The main strategies used for redistribution were:

- taking some from one doll and giving to another, in several moves,

- starting again and dealing, either in ones or twos,

- taking two from each original doll and giving to the new doll,

- collecting the biscuits and crumbling them into a heap, then sharing out handfuls of crumbs.

Surprisingly, the quickest solution, of taking two from each, was used by some children who were not yet counting and would not have been considered mathematically proficient. The last strategy of crumbling the biscuits was not anticipated by researchers, who reluctantly acknowledged it was a successful solution

(and indicated some creative problem solving!). The researchers also concluded that some children were prompted by this problem to reveal an intuitive understanding of ratio, as they could just 'see' how to split six biscuits in the ratio 2:1; they also seemed to recognise that this would result in three equal numbers. This problem therefore engages children in a range of mathematical skills and

ideas, such as counting, subitising, comparing and recognising numerical relationships. It is an educationally useful problem because it can be tackled successfully by all children, whatever their mathematical proficiency, and gives experience of adapting a range of mathematical knowledge in the stages of problem solving, by devising a strategy and checking that a solution had been reached.

Surprisingly, the quickest solution, of taking two from each, was used by some children who were not yet counting and would not have been considered mathematically proficient. The last strategy of crumbling the biscuits was not anticipated by researchers, who reluctantly acknowledged it was a successful solution

(and indicated some creative problem solving!). The researchers also concluded that some children were prompted by this problem to reveal an intuitive understanding of ratio, as they could just 'see' how to split six biscuits in the ratio 2:1; they also seemed to recognise that this would result in three equal numbers. This problem therefore engages children in a range of mathematical skills and

ideas, such as counting, subitising, comparing and recognising numerical relationships. It is an educationally useful problem because it can be tackled successfully by all children, whatever their mathematical proficiency, and gives experience of adapting a range of mathematical knowledge in the stages of problem solving, by devising a strategy and checking that a solution had been reached.Sharing problems are very useful because they are familiar and purposeful, and the level of difficulty can be easily adapted: for instance this problem can be simplified to just six biscuits; the pirate panda version in Mathematics Story Time includes more toys, and Pat Hutchins' story, 'The Doorbell Rang' (Using Books) is essentally the same problem with more biscuits and an ever increasing number of children. Variations can include remainders, such as 10 shared between three: it is interesting to see if children suggest solutions such as subtracting one (usually by eating the extra one) adding two more, or dividing into thirds. If children have relevant experience of fractions, even four year olds can tackle problems such as four biscuits shared between three, or seven shared between four (Anthony and Walshaw, 2007:181). Therefore sharing problems can involve a range of mathematics ideas, from 'same number' to fractions of wholes and numbers.

Problem-solving processes and strategies

As identified in Jennie Pennant's article, Developing Excellence in Problem Solving with Young Learners, the stages of problem solving include 'getting started', 'working on the problem', 'digging deeper' and 'reflecting'. Of course, some children may just rush towards a solution

without going through preliminary or reflective stages. Deloache and Brown (1987) observed the following levels of sophistication in approaches, with two to three year olds ordering nesting cups and four to seven year olds making a train-track circuit:

As identified in Jennie Pennant's article, Developing Excellence in Problem Solving with Young Learners, the stages of problem solving include 'getting started', 'working on the problem', 'digging deeper' and 'reflecting'. Of course, some children may just rush towards a solution

without going through preliminary or reflective stages. Deloache and Brown (1987) observed the following levels of sophistication in approaches, with two to three year olds ordering nesting cups and four to seven year olds making a train-track circuit:- brute force: trying to hammer bits so that they fit,

- local correction: adjusting one part, often creating a different problem,

- dismantling: starting all over again,

- holistic review: considering multiple relations or simultaneous adjustments e.g. repairing by insertion and reversal.

Research suggests that mathematical problem solving processes look essentially the same at any age and young children employ similar strategies to older ones: it is experience rather than age which makes a difference, according to Askew and Wiliam (1995). At the different stages in the process, successful problem solvers' strategies include:

- getting a feel for the problem, looking at it holistically, checking they have understood e.g. talking it through or asking questions;

- planning, preparing and predicting outcomes e.g. gathering blocks together before building;

- monitoring progress towards the goal e.g. checking that the bears will fit the houses;

- being systematic, trying possibilities methodically without repetition, rather than at random, e.g. separating shapes tried from those not tried in a puzzle;

- trying alternative approaches and evaluating strategies e.g. trying different positions for shapes;

- refining and improving solutions e.g. solving a puzzle again in fewer moves (Gifford, 2005: 153).

Supporting children's problem solving

Adults can therefore help children to be aware of processes and strategies, and to review their initial solution and consider alternatives. Burton (1984) suggested that children be taught to use 'self-organising questions' at the different stages. Examples for younger children might be:

- Getting to grips: What are we trying to do?

- Connecting to previous experience: Have we done anything like this before?

- Planning: What do we need?

- Considering alternative methods: Is there another way?

- Monitoring progress: How does it look so far?

- Evaluating solutions: Does it work? How can we check? Could we make it even better?

Assessing problem solving: Characteristics of effective learning

As well as demonstrating children's understanding and use of mathematical ideas, problem solving clearly allows children to demonstrate the EYFS 'Characteristics of effective learning' in mathematics (see the Early Years Foundation Stage Framework): it involves children in Playing and exploring, Active learning and Creating and thinking critically, as exemplified for inspectors of mathematics in the chart below (Ofsted, 2013). This includes aspects such as being willing to 'have a go' and noticing patterns, as well as making decisions about problem solving, including planning, checking, changing strategy and reviewing.

Most importantly, rich problems develop children's confidence and flexibility in using the mathematics knowledge they have to choose and create strategies, developing problem-solving skills for life.

Useful resources

- Construction - finding shapes which fit together or balance

- Pattern-making - creating a rule to create a repeating pattern

- Shape pictures - selecting shapes with properties to represent something

- Puzzles - finding ways of fitting shapes to fit a puzzle

- Role-play areas - working out how much to pay in a shop

- Measuring tools - finding out how different kinds of scales work

- Nesting, posting, ordering - especially if they are not obvious

- Robots - e.g. beebots: directing and making routes

Balances, Mud Kitchen, Building Towers, Making a Picture, Collecting

Routine activities

- preparing, getting the right number e.g. scissors, paper for creative activities

- sharing equal amounts e.g. at snack time

- tidying up, checking nothing is lost

- gardening and cooking e.g. working out how many bulbs to plant where, measuring amounts in a recipe using scales or jugs

- games, developing rules, variations and scoring

- PE: organising in groups, timing and recording

Tidying, Packing, Cooking, Playing Incey Wincey Spider

Discussion sessions

- Decision making - what shall we call the new guinea pig?

- Parties, picnics and trips e.g. how much lemonade shall we make?

- Design Projects - the role play area, new outdoor gardens or circuits

- Hiding games - feely bags with shapes, the 'Box' game

- Story problems - e.g. unfair sharing, with remainders and fractions, making things to fit giants or fairies

Shapes in the Bag, Number Rhymes, Maths Story Time, Using Books

NB: Other books for problem posing include: 'The Shopping Basket', 'The Great Pet Sale'

See also New Zealand government website 'Picture books with mathematical content'.

References

Anthony, G. & M. Walshaw (2007) Effective pedagogy in mathematics/pangarau:

best evidence synthesis (BES) Wellington, NZ: Ministry of Education p.181

http://educationcounts.edcentre.govt.nz/publications/curriculum/bes-eff-pedagogy.html

Askew, M. & D. Wiliam (1995). Recent research in mathematics education 5-

16. London, HMSO.

Burton, L. (1984). Thinking Things Through: Problem solving in mathematics. London, Basil Blackwell.

Carr, M., S. Peters, et al. (1994). Early childhood mathematics: Finding the right level of challenge. Mathematics education: a handbook for teachers. J. Neyland. Wellington, Wellington College of education. 1: 271-282.

Coltman, P., D. Petyaeva, et al. (2002). "Scaffolding learning through meaningful tasks and adult interaction." Early Years 22(1): 39-49.

Curtis, A. (1998). A curriculum for the pre-school child: learning to learn. London, Routledge.

Davis, G. & K. Pepper (1992). "Mathematical problem solving by pre-school children." Educational Studies in Mathematics 23: 397-415.

Deloache, J., S. & A. Brown, M. (1987). The early emergence of planning skills in children. The child's construction of the world. J. Bruner and H. Haste. London, Methuen: 108-130.

Gifford, S. (2005) Teaching mathematics 3-5: developing learning in the foundation stage Maidenhead: Open University Press/McGraw-Hill Education

Gura, P. (1992). Exploring learning: young children and blockplay. London, Paul

Chapman Publishing Ltd.

Office for Standards in Education. (2013). Mathematics in school inspection January 2013: Information pack for training. Retrieved from

https://www.whatdotheyknow.com/request/additional_guidance_for_inspecto