Skip over navigation

Thank you very much to Pablo and Sergio from King's College Alicante in Spain, Amrit from Hymers College in the UK, Jacob and Michael from Cedar House School in South Africa, Alex from Bexley Grammar School in the UK and Niklas from Walton High School in the UK, who all sent in good work on this problem. The solution below draws on their observations and explanations.

Moving $z_1$ and $z_2$ about, there are lots of ways to make $z_3=z_1+z_2$ a real number, which lies on the real axis.

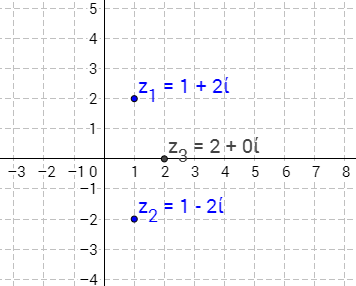

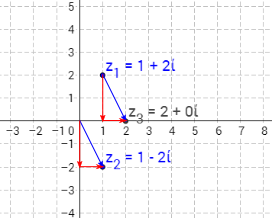

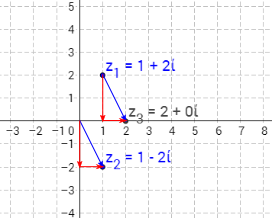

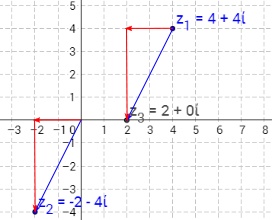

$z_1$ and $z_2$ need to be on either side of the real axis, and both the same vertical distance from the real axis. They can be directly above each other, but they don't have to be. Here are a couple of examples:

$(1+2i)+(1-2i)=2+0i$

$(1+2i)+(1-2i)=2+0i$

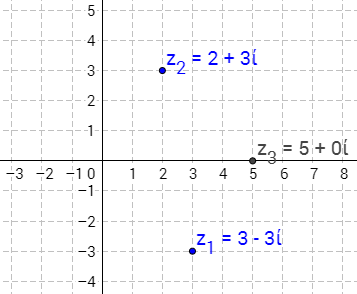

$(3-3i)+(2+3i)=5+0i$

$(3-3i)+(2+3i)=5+0i$

Notice that moving $z_1$ and $z_2$ horizontally gives other real sums:

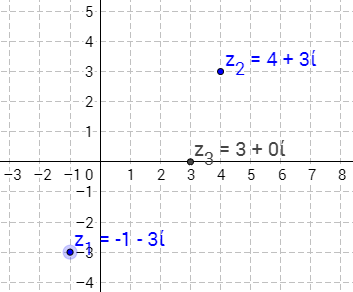

$(-1-3i)+(4+3i)=3+0i$

$(-1-3i)+(4+3i)=3+0i$

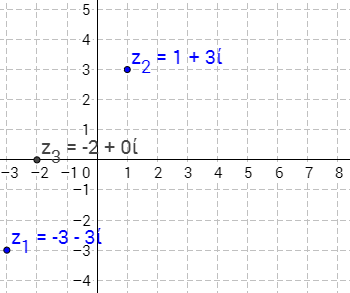

$(-3-3i)+(1+3i)=-2+0i$

$(-3-3i)+(1+3i)=-2+0i$

For these last three examples, $z_1=a_1-3i$ and $z_2=a_2+3i$ for some real numbers $a_1$ and $a_2$.

We can check this will always work:

$$z_1+z_2=(a_1-3i)+(a_2+3i)=a_1+a_2-3i+3i=(a_1+a_2)+0i$$

What if we had another pair in the form $a_1+bi$ and $a_2-bi$ (for some real number $b$)?

Then $$z_1+z_2=(a_1+bi)+(a_2-bi)=a_1+a_2+bi-bi=(a_1+a_2)+0i$$ So whenever $z_1=a_1+bi$ and $z_2=a_2-bi$, $z_1+z_2$ will be real.

How it works geometrically

When you add $z_2$ to $z_1$, you add the real parts, $a_1+a_2$, so $z_1$ is moved by $a_2$ along the real axis. The imaginary parts are also added, $b_1+b_2$, so $z_1$ is moved by $b_2$ along the imaginary axis.

This is the same as a translation by the vector from $0+0i$ to $z_2$:

$(1+2i)+(1-2i)=2+0i$

$(4+4i)+(-2-4i)=2+0i$

We can also prove algebraically that $z_1+z_2$ is only ever a real number if $z_1=a_1+bi$ and $z_2=a_2-bi$.

To do this, we should begin by letting $z_1$ and $z_2$ be any complex numbers, so $z_1=a_1+b_1i$ and $z_2=a_2+b_2i$.

Then: $$z_1+z_2=(a_1+b_1i)+(a_2+b_2i)=(a_1+a_2)+(b_1+b_2)i$$

This is real only if the imaginary part is equal to $0i$,

so $(b_1+b_2)i=0i$, so $b_1+b_2=0$, which means $b_2=-b_1$.

So $z_1=a_1+bi$ and $z_2=a_2-bi$.

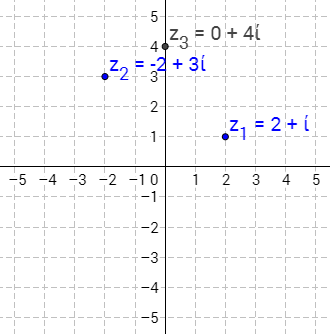

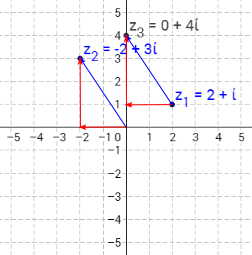

Adding two complex numbers to get an imaginary number is very similar.

Here are some examples:

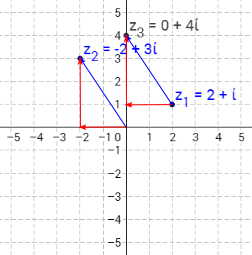

$(2+i)+(-2+3i)=0+4i$

$(2+i)+(-2+3i)=0+4i$

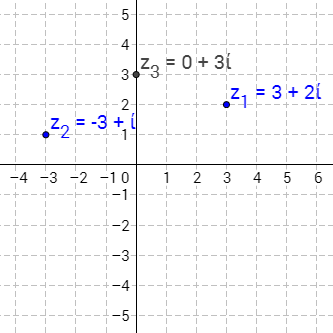

$(3+2i)+(-3+i)=0+3i$

$(3+2i)+(-3+i)=0+3i$

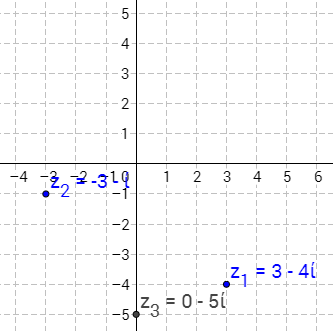

$(3-4i)+(-3-i)=0-5i$

$(3-4i)+(-3-i)=0-5i$

Similarly, notice that if $z_1=a+b_1i$ and $z_2=-a+b_2i$ then $z_1+z_2=0+(b_1+b_2)i$, which is imaginary (if $b_1+b_2=0$, then $z_1+z_2=0+0i$, which is real - but $0+0i$ is considered to be both real and imaginary).

Geometrically, now the horizontal distances to the imaginary axis are equal and opposite. This means that translation by $z_2$ 'cancels out' the real component of $z_1$:

We can prove that $z_1$ and $z_2$ must be of the form $a+b_1i$ and $-a+b_2i$ for their sum to be imaginary just like we proved the similar result for the sum to be real:

Let $z_1=a_1+b_1i$ and $z_2=a_2+b_2i$.

Then: $$z_1+z_2=(a_1+b_1i)+(a_2+b_2i)=(a_1+a_2)+(b_1+b_2)i$$

This is imaginary only if the real part is equal to $0$, so $a_1+a_2=0$, so $a_2=-a_1$.

Therefore $z_1=a+b_1i$ and $z_2=-a+b_2i$.

Or search by topic

Number and algebra

Geometry and measure

Probability and statistics

Working mathematically

Advanced mathematics

For younger learners

Opening the Door

Age 14 to 18

Challenge Level

- Problem

- Student Solutions

Thank you very much to Pablo and Sergio from King's College Alicante in Spain, Amrit from Hymers College in the UK, Jacob and Michael from Cedar House School in South Africa, Alex from Bexley Grammar School in the UK and Niklas from Walton High School in the UK, who all sent in good work on this problem. The solution below draws on their observations and explanations.

Moving $z_1$ and $z_2$ about, there are lots of ways to make $z_3=z_1+z_2$ a real number, which lies on the real axis.

$z_1$ and $z_2$ need to be on either side of the real axis, and both the same vertical distance from the real axis. They can be directly above each other, but they don't have to be. Here are a couple of examples:

Notice that moving $z_1$ and $z_2$ horizontally gives other real sums:

For these last three examples, $z_1=a_1-3i$ and $z_2=a_2+3i$ for some real numbers $a_1$ and $a_2$.

We can check this will always work:

$$z_1+z_2=(a_1-3i)+(a_2+3i)=a_1+a_2-3i+3i=(a_1+a_2)+0i$$

What if we had another pair in the form $a_1+bi$ and $a_2-bi$ (for some real number $b$)?

Then $$z_1+z_2=(a_1+bi)+(a_2-bi)=a_1+a_2+bi-bi=(a_1+a_2)+0i$$ So whenever $z_1=a_1+bi$ and $z_2=a_2-bi$, $z_1+z_2$ will be real.

How it works geometrically

When you add $z_2$ to $z_1$, you add the real parts, $a_1+a_2$, so $z_1$ is moved by $a_2$ along the real axis. The imaginary parts are also added, $b_1+b_2$, so $z_1$ is moved by $b_2$ along the imaginary axis.

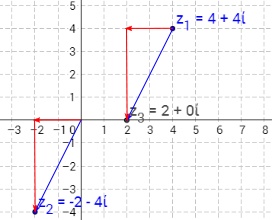

This is the same as a translation by the vector from $0+0i$ to $z_2$:

$(1+2i)+(1-2i)=2+0i$

$(4+4i)+(-2-4i)=2+0i$

We can also prove algebraically that $z_1+z_2$ is only ever a real number if $z_1=a_1+bi$ and $z_2=a_2-bi$.

Then: $$z_1+z_2=(a_1+b_1i)+(a_2+b_2i)=(a_1+a_2)+(b_1+b_2)i$$

This is real only if the imaginary part is equal to $0i$,

so $(b_1+b_2)i=0i$, so $b_1+b_2=0$, which means $b_2=-b_1$.

So $z_1=a_1+bi$ and $z_2=a_2-bi$.

Adding two complex numbers to get an imaginary number is very similar.

Here are some examples:

Similarly, notice that if $z_1=a+b_1i$ and $z_2=-a+b_2i$ then $z_1+z_2=0+(b_1+b_2)i$, which is imaginary (if $b_1+b_2=0$, then $z_1+z_2=0+0i$, which is real - but $0+0i$ is considered to be both real and imaginary).

Geometrically, now the horizontal distances to the imaginary axis are equal and opposite. This means that translation by $z_2$ 'cancels out' the real component of $z_1$:

We can prove that $z_1$ and $z_2$ must be of the form $a+b_1i$ and $-a+b_2i$ for their sum to be imaginary just like we proved the similar result for the sum to be real:

Let $z_1=a_1+b_1i$ and $z_2=a_2+b_2i$.

Then: $$z_1+z_2=(a_1+b_1i)+(a_2+b_2i)=(a_1+a_2)+(b_1+b_2)i$$

This is imaginary only if the real part is equal to $0$, so $a_1+a_2=0$, so $a_2=-a_1$.

Therefore $z_1=a+b_1i$ and $z_2=-a+b_2i$.

You may also like

Roots and Coefficients

If xyz = 1 and x+y+z =1/x + 1/y + 1/z show that at least one of these numbers must be 1. Now for the complexity! When are the other numbers real and when are they complex?

Target Six

Show that x = 1 is a solution of the equation x^(3/2) - 8x^(-3/2) = 7 and find all other solutions.

8 Methods for Three by One

This problem in geometry has been solved in no less than EIGHT ways by a pair of students. How would you solve it? How many of their solutions can you follow? How are they the same or different? Which do you like best?