Skip over navigation

Or search by topic

Number and algebra

Geometry and measure

Probability and statistics

Working mathematically

Advanced mathematics

For younger learners

Rollin' Rollin' Rollin'

Age 11 to 14

Challenge Level

- Problem

- Getting Started

- Student Solutions

- Teachers' Resources

Why do this problem?

This problem is interesting because the answer is not at all obvious and will challenge students' perceptions. It is a great problem in visualisation and translating a visual concept into numbers or algebra.Possible approach

Start with the problem of two disks of the same size, one rolling around the other.

Discuss the problem and canvass the class for their instinctive response: how many revolutions will the first disk make? Ask them to go off and justify this response. Those who incorrectly assume that the disk turns one time will either become aware of their error or produce a faulty justification of their result.

The class could then discuss their result and give their explanations (faulty or otherwise). Choose two students with different results to present their ideas. Who convinces the rest of the class? [note: if the whole class is correct, then who can give the clearest explanation? If the whole class is incorrect then watch the animation and ask at what point the rolling disk is in the same

orientation as at the start]

Even when the correct answer has been worked out, students are likely to want to demonstrate this with physical objects such as a pair of coins.

The activity contains many extensions which are likely to become accessible once the initial problem is grasped.

Key questions

- How far does the centre of the rolling disk travel?

- Can you visualise the locus of a point on the edge of the rolling disk?

Possible extension

Can students find a rule for the number of revolutions when a disk of radius $r$ rolls around a disk of radius $m$? Rolling around a polygon could also usefully be investigated.Possible support

If you have access to 'Spirograph'-type resources the demonstration of a disk rolling around another becomes easier due to the teeth on the wheels. Playing with the interactivity for various settings also will help to develop intuition.You may also like

Is There a Theorem?

Draw a square. A second square of the same size slides around the first always maintaining contact and keeping the same orientation. How far does the dot travel?

The Old Goats

A rectangular field has two posts with a ring on top of each post. There are two quarrelsome goats and plenty of ropes which you can tie to their collars. How can you secure them so they can't fight each other but can reach every corner of the field?

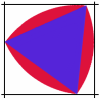

Rolling Triangle

The triangle ABC is equilateral. The arc AB has centre C, the arc BC has centre A and the arc CA has centre B. Explain how and why this shape can roll along between two parallel tracks.