Skip over navigation

+abs(x)=1.gif)

This solution was submitted by Curt from Reigate College. Well done Curt.

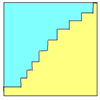

(1) Explain the features of the graph of the relation $|x|+|y|=1.$

If the above equation is true then neither $|x|$ nor $|y|$ can be greater than 1. If say $1+h =|x| > 1$, we have: $1+h + |y| =1$ and so $|y| = -h < 0$, a contradiction, as $|a|\geq 0$ for any $a$. Therefore, this function is not defined for values of $x$ and $y$ greater than 1.

I now quote without proof the fact that if $|a| = t$ then $a =t$ or $a= -t$. This is useful when applied in this problem.

If $|y| = 1- |x|$ then $y = 1 - |x|$ or $y = -1 + |x|$. If $y = 1- |x|$ then $y= 1 + x$ or $y= 1-x$. Similarly, if $y = -1 + |x|$, then $y=x-1$ or $y=-x-1$.

The graph is the line segments (where $-1< x< 1$ and $-1< y< 1$) given by: $y=1-x$ in the first quadrant; $y=1+x$ in the second quadrant; $y=-1-x$ in the third quadrant and $y=x-1$ in the fourth quadrant.

Editor's note: By symmetry if $(a,b)$ satisfies this relation then so does $$(b,a),\ (-a,b)\ (-b,a)\ (-a,-b),\ (-b,-a),\ (a,-b),\ {\rm and}\ (b,-a)$$ so the graph is the square consisting of the four line segments described.

The line segments are perpendicular and intersect at (0,1), (-1,0) (0,-1) and (1,0). The square shape with vertices at the above co-ordinates, has symmetry in $y=x$, $y= -x$, $y=0$ and $x=0$. I refer to this as a graph, not a function, due to one-to-many relation.

2) As $n/(n+1)$ can be written as $1/(1+1/n)$, by dividing both numerator and denominator by $n$ we consider: $$\eqalign{ \left(1+{1\over n}\right)^n &= 1 + n\left({1\over n}\right) + {n(n-1)\over 2}\left({1\over n}\right)^2 + \ldots \cr &= 2 + \ldots \geq 2 > 1 .}$$ Taking the nth root $$1+ {1\over n} \geq 2^{1/n} > 1^{1/n} =1$$ Hence $$ {1\over(1+1/n)}={n\over(n+1)} \leq {1\over 2^{1/n}} < 1.$$

(3) Taking the simple case $x^2 + y^2 = 1$ (the circle), and considering the first quadrant, it will be shown that $y$ decreases as $x$ increases. As this is in the first quadrant, the positive root alone is considered: $y = (1-x^2)^{1/2}.$ As $x$ increases to a maximum value of 1 on the interval $0 \leq x \leq 1$ so $x^2$ increases monotonically and $f(x)=1-x^2$ decreases monotonically (to confirm, check f'(x)=-2x).

If we have $f(x_1)> f(x_2)$ (with $x_1< x_2$), then taking the positive square root of both sides, we have ${f(x_1)}^{1/2} > {f(x_2)}^{1/2}$. So as $x$ increases, $y$ decreases.

This same method could be extended to all values of $n$. For $g(x) = 1-x^n$ then $g(x+h)< g(x)$ for $h> 0$ because $x^n$ increases monotonically on the interval $0< x< 1$. Clearly, if $x_1< x_2 $ then $x_1^n< x_2^n$ so $1-x_1^n> 1-x_2^n$ and hence $g(x_1)> g(x_2)$. Taking the positive nth root of both sides, we get: $y_1 = {g(x_1)}^{1/n}> {g(x_2)}^{1/n}=y_2$. So $y_1 > y_2$ for $x_1 < x_2$ ; hence as $x$ increases in the first quadrant, $y$ decreases.

Editor's note: Alternatively we can use calculus to prove this. Fixing one value of $n$ in $x^n+y^n=1$: $$\eqalign{ y^n &= 1-x^n \cr ny^{n-1}{dy\over dx} &= -nx^{n-1}\cr {dy\over dx}&= -{x^{n-1}\over y^{n-1}} < 0.}$$ As $x$ and $y$ are positive in the first quadrant we see that the derivative is negative which shows that $y$ decreases as $x$ increases.

When $x=y$, on the general graph $x^n + y^n = 1$ we get $2x^n=1$ so $x=y=1/(2^{1/n})$. From earlier in this question, we have for $n> 1$, $${n\over n+1} < {1\over 2^{1/n}}$$ so $x=y > n/(n+1)$. Therefore, as there is only one solution to $2x^n = 1$ in the first quadrant, the graph should lie outside the square with coordinates: $$(0,0),\ (0, n/(n+1)),\ (n/(n+1), n/(n+1)),\ (n/(n+1),0)$$ In the first quadrant, as $x,y\geq 0$, and on $x^n + y^n = 1$, neither $x$ nor $y$ may be greater than 1, there are no co-ordinates on the curve for which $x,y> 1$. If $x> 1$ then $x^n=1+g$, for $g> 0$ so $y^n=-g$, which is not allowed in the first quadrant. The curve must lie inside (or on at the co-ordinate axes) the square with coordinates (1,0), (0,1), (1,1), (0,0) NB, the curve will touch the square only at vertices (1,0) and (0,1).

(4) As $n \to \infty$, $1/(1+1/n) = n/(1+n) \to 1$.

The square which the curve must lie within is fixed (as above). However, as $n$ increases, the square which the curve must lie outside of gets increasingly large. As the curve is squeezed between two squares, its shape becomes increasingly more squared.

For curves where $n$ is even, the curve becomes squeezed in all four quadrants because, by symmetry (exactly as in part (1) of this question) the graph is symmetric about $y=x$, $y=-x$, $y=0$ and about $x=0$.

Or search by topic

Number and algebra

Geometry and measure

Probability and statistics

Working mathematically

Advanced mathematics

For younger learners

Squareness

Age 16 to 18

Challenge Level

- Problem

- Getting Started

- Student Solutions

- Teachers' Resources

+abs(x)=1.gif)

This solution was submitted by Curt from Reigate College. Well done Curt.

(1) Explain the features of the graph of the relation $|x|+|y|=1.$

If the above equation is true then neither $|x|$ nor $|y|$ can be greater than 1. If say $1+h =|x| > 1$, we have: $1+h + |y| =1$ and so $|y| = -h < 0$, a contradiction, as $|a|\geq 0$ for any $a$. Therefore, this function is not defined for values of $x$ and $y$ greater than 1.

I now quote without proof the fact that if $|a| = t$ then $a =t$ or $a= -t$. This is useful when applied in this problem.

If $|y| = 1- |x|$ then $y = 1 - |x|$ or $y = -1 + |x|$. If $y = 1- |x|$ then $y= 1 + x$ or $y= 1-x$. Similarly, if $y = -1 + |x|$, then $y=x-1$ or $y=-x-1$.

The graph is the line segments (where $-1< x< 1$ and $-1< y< 1$) given by: $y=1-x$ in the first quadrant; $y=1+x$ in the second quadrant; $y=-1-x$ in the third quadrant and $y=x-1$ in the fourth quadrant.

Editor's note: By symmetry if $(a,b)$ satisfies this relation then so does $$(b,a),\ (-a,b)\ (-b,a)\ (-a,-b),\ (-b,-a),\ (a,-b),\ {\rm and}\ (b,-a)$$ so the graph is the square consisting of the four line segments described.

The line segments are perpendicular and intersect at (0,1), (-1,0) (0,-1) and (1,0). The square shape with vertices at the above co-ordinates, has symmetry in $y=x$, $y= -x$, $y=0$ and $x=0$. I refer to this as a graph, not a function, due to one-to-many relation.

2) As $n/(n+1)$ can be written as $1/(1+1/n)$, by dividing both numerator and denominator by $n$ we consider: $$\eqalign{ \left(1+{1\over n}\right)^n &= 1 + n\left({1\over n}\right) + {n(n-1)\over 2}\left({1\over n}\right)^2 + \ldots \cr &= 2 + \ldots \geq 2 > 1 .}$$ Taking the nth root $$1+ {1\over n} \geq 2^{1/n} > 1^{1/n} =1$$ Hence $$ {1\over(1+1/n)}={n\over(n+1)} \leq {1\over 2^{1/n}} < 1.$$

(3) Taking the simple case $x^2 + y^2 = 1$ (the circle), and considering the first quadrant, it will be shown that $y$ decreases as $x$ increases. As this is in the first quadrant, the positive root alone is considered: $y = (1-x^2)^{1/2}.$ As $x$ increases to a maximum value of 1 on the interval $0 \leq x \leq 1$ so $x^2$ increases monotonically and $f(x)=1-x^2$ decreases monotonically (to confirm, check f'(x)=-2x).

If we have $f(x_1)> f(x_2)$ (with $x_1< x_2$), then taking the positive square root of both sides, we have ${f(x_1)}^{1/2} > {f(x_2)}^{1/2}$. So as $x$ increases, $y$ decreases.

This same method could be extended to all values of $n$. For $g(x) = 1-x^n$ then $g(x+h)< g(x)$ for $h> 0$ because $x^n$ increases monotonically on the interval $0< x< 1$. Clearly, if $x_1< x_2 $ then $x_1^n< x_2^n$ so $1-x_1^n> 1-x_2^n$ and hence $g(x_1)> g(x_2)$. Taking the positive nth root of both sides, we get: $y_1 = {g(x_1)}^{1/n}> {g(x_2)}^{1/n}=y_2$. So $y_1 > y_2$ for $x_1 < x_2$ ; hence as $x$ increases in the first quadrant, $y$ decreases.

Editor's note: Alternatively we can use calculus to prove this. Fixing one value of $n$ in $x^n+y^n=1$: $$\eqalign{ y^n &= 1-x^n \cr ny^{n-1}{dy\over dx} &= -nx^{n-1}\cr {dy\over dx}&= -{x^{n-1}\over y^{n-1}} < 0.}$$ As $x$ and $y$ are positive in the first quadrant we see that the derivative is negative which shows that $y$ decreases as $x$ increases.

When $x=y$, on the general graph $x^n + y^n = 1$ we get $2x^n=1$ so $x=y=1/(2^{1/n})$. From earlier in this question, we have for $n> 1$, $${n\over n+1} < {1\over 2^{1/n}}$$ so $x=y > n/(n+1)$. Therefore, as there is only one solution to $2x^n = 1$ in the first quadrant, the graph should lie outside the square with coordinates: $$(0,0),\ (0, n/(n+1)),\ (n/(n+1), n/(n+1)),\ (n/(n+1),0)$$ In the first quadrant, as $x,y\geq 0$, and on $x^n + y^n = 1$, neither $x$ nor $y$ may be greater than 1, there are no co-ordinates on the curve for which $x,y> 1$. If $x> 1$ then $x^n=1+g$, for $g> 0$ so $y^n=-g$, which is not allowed in the first quadrant. The curve must lie inside (or on at the co-ordinate axes) the square with coordinates (1,0), (0,1), (1,1), (0,0) NB, the curve will touch the square only at vertices (1,0) and (0,1).

(4) As $n \to \infty$, $1/(1+1/n) = n/(1+n) \to 1$.

The square which the curve must lie within is fixed (as above). However, as $n$ increases, the square which the curve must lie outside of gets increasingly large. As the curve is squeezed between two squares, its shape becomes increasingly more squared.

For curves where $n$ is even, the curve becomes squeezed in all four quadrants because, by symmetry (exactly as in part (1) of this question) the graph is symmetric about $y=x$, $y=-x$, $y=0$ and about $x=0$.

(5) In the first quadrant the graph of the relation $x^3 + y^3

= 1$ behaves similarly to other graphs where $n$ is even. However,

the graph cannot be defined in the third quadrant for $x< 0$ and

$y < 0$, for that would lead to the sum of two negative numbers

being 1, which is not possible. The function is also defined for

$x> 1$, for negative numbers do have real cube roots. If $x^3 =

1+a$ then $y^3 = -a$ and so $y=-a^{1/3}$ and $x = (1+a)^{1/3}$. For

large $x$ (large $a$) this shows that $x \approx -y$, therefore the

graph reaches an asymptote with $y= -x$. The same thing happens as

$x \to -\infty$ in the second quadrant.

The same features occur for the whole family of graphs of $x^n

+ y^n=1$ for odd $n$.

The graphs of $|x^n| + |y^n| = 1$ for odd $n$ would have the

symmetrical squarish shape, reflecting the family of graphs in the

first quadrant into the remaining quadrants (see part 1).

You may also like

Small Steps

Two problems about infinite processes where smaller and smaller steps are taken and you have to discover what happens in the limit.