Skip over navigation

This solution is from Etienne of Parramatta Highschool, NSW Australia

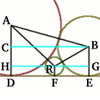

I need to prove the area of a triangle $ XYZ $ is given by $ Area = rs $ where $ r $ is the radius of the incircle (inscribed circle) and $ s$ is the semi-perimeter (half the perimeter $ (x+y+z)/2$). Let $ x $, $ y $, $ z $ be the lengths of the sides of triangle $ XYZ $. Join the incentre $I$ of the triangle to the $3$ corners. From $I$ drop $3$ perpendiculars to each of the sides, each of these has a length of $ r $. The areas of $ XYI $, $ YZI $, $ ZXI $ are $ zr/2 $, $ xr/2 $ and $ yr/2 $ respectively. They sum up to give the area of triangle $ XYZ $

Area of $ XYZ = zr/2 + xr/2 + yr/2 = r(x+y+z)/2 = rs $.

Back to the question!

When $ P $ is the midpoint of $ AD, r_1 = r_2 $ because they sit on congruent triangles. The area of triangle $ ABP = AP \times AB/2 = 1/4. $

By Pythagoras' Theorem, $ PB = \sqrt(1+1/4) = \sqrt5/2. $

The semi perimeter of $ ABP = (1 + 1/2 + \sqrt5/2)/2 = [3+\sqrt5]/4. $ Using the formula $ A = rs $ for the area of the triangle, the area of $ ABP = r_1[3+\sqrt5]/4 = 1/4. $ This gives $ r_1 = 1/[3 + \sqrt5] = [3 - \sqrt5]/4 $ so $ r_1 = r_2 = [3 - \sqrt5]/4. $

The area of $BPC$ is $1 - 1/4 - 1/4 = 1/2$ and $ PB = PC = \sqrt5/2. $

The semi-perimeter of $ BPC = [1+ \sqrt5/2 + \sqrt5/2]/2 = [1 + \sqrt5]/2. $ From the area of triangle $ BPC $ we get $ r_3[1 + \sqrt5]/2 = 1/2 $ so $ r_3 = 1/[1 + \sqrt5] = [\sqrt5 - 1]/4. $

Now suppose the lengths AP and PD are $ 1-p $ and $ p $. The area of $ APB = (1-p)/2. $ The length $ PB = \sqrt(1 + p^2 - 2p + 1) = \sqrt(p^2 - 2p + 2) $ and the semi perimeter of $ APB = [1 + (1-p) + \sqrt(p^2 - 2p + 2)]/2.$ So, using the area formula again,

$$ r_2 = {1-p\over 2} \times {2\over [2 - p + \sqrt(p^2 - 2p + 2)]} = {1\over 2}[2 - p - \sqrt(p^2 - 2p + 2)]. $$

Similary with $ DPC $. The area of $ DPC = p/2 $ and the length $ PC = \sqrt(p^2 + 1). $ The semi perimeter of $ PC = [1 + p + \sqrt(p^2 + 1)]/2. $ So

$$ r_1 = {p\over 2} \times {2\over [1 + p + \sqrt(p^2 + 1)]} = {1\over 2}[1 + p - \sqrt(p^2 + 1)]. $$

Similarly $$ r_3 = {1\over 2} \times {2\over [1 + \sqrt(p^2 + 1) + \sqrt(p^2 -2p + 2)]} = {1\over 2}[1 + \sqrt(p^2 + 1) - \sqrt(p^2 -2p +2)][\sqrt(p^2 +1)- p]. $$

To finish this question you need to use the formulae found above which give the radii $ r_1 $, $ r_2$ and $ r_3 $ in terms of $ p $ and then consider how these values change as $ p $ varies from $0$ to $1$. For example $ r_1 $ varies from $0$ to approximately $0.293$ as $ p $ increases from $0$ to $1$.

In order to discover whether the ratio of the radii $ r_1 : r_2 : r_3 $ can ever take the value $1 : 2 : 3$ you could look at the above graphs of $ r_1 $, $ r_2 $ and $ r_3 $ as $ p $ varies from $0$ to $1$.

$r_2$ must be twice the value of $r_1$ and by inspection you can see that the only place where this is possible is when $p$ is between $0.2$ and $0.3$. We also need $r_3$ to be $3/2$ times the value of $r_2$, but this is not the case when $p$ is between $0.2$ and $0.3$. Therefore the ratio $1:2:3$ can never occur.

Or search by topic

Number and algebra

Geometry and measure

Probability and statistics

Working mathematically

Advanced mathematics

For younger learners

Sangaku

Age 16 to 18

Challenge Level

- Problem

- Student Solutions

This solution is from Etienne of Parramatta Highschool, NSW Australia

I need to prove the area of a triangle $ XYZ $ is given by $ Area = rs $ where $ r $ is the radius of the incircle (inscribed circle) and $ s$ is the semi-perimeter (half the perimeter $ (x+y+z)/2$). Let $ x $, $ y $, $ z $ be the lengths of the sides of triangle $ XYZ $. Join the incentre $I$ of the triangle to the $3$ corners. From $I$ drop $3$ perpendiculars to each of the sides, each of these has a length of $ r $. The areas of $ XYI $, $ YZI $, $ ZXI $ are $ zr/2 $, $ xr/2 $ and $ yr/2 $ respectively. They sum up to give the area of triangle $ XYZ $

Area of $ XYZ = zr/2 + xr/2 + yr/2 = r(x+y+z)/2 = rs $.

Back to the question!

When $ P $ is the midpoint of $ AD, r_1 = r_2 $ because they sit on congruent triangles. The area of triangle $ ABP = AP \times AB/2 = 1/4. $

By Pythagoras' Theorem, $ PB = \sqrt(1+1/4) = \sqrt5/2. $

The semi perimeter of $ ABP = (1 + 1/2 + \sqrt5/2)/2 = [3+\sqrt5]/4. $ Using the formula $ A = rs $ for the area of the triangle, the area of $ ABP = r_1[3+\sqrt5]/4 = 1/4. $ This gives $ r_1 = 1/[3 + \sqrt5] = [3 - \sqrt5]/4 $ so $ r_1 = r_2 = [3 - \sqrt5]/4. $

The area of $BPC$ is $1 - 1/4 - 1/4 = 1/2$ and $ PB = PC = \sqrt5/2. $

The semi-perimeter of $ BPC = [1+ \sqrt5/2 + \sqrt5/2]/2 = [1 + \sqrt5]/2. $ From the area of triangle $ BPC $ we get $ r_3[1 + \sqrt5]/2 = 1/2 $ so $ r_3 = 1/[1 + \sqrt5] = [\sqrt5 - 1]/4. $

Now suppose the lengths AP and PD are $ 1-p $ and $ p $. The area of $ APB = (1-p)/2. $ The length $ PB = \sqrt(1 + p^2 - 2p + 1) = \sqrt(p^2 - 2p + 2) $ and the semi perimeter of $ APB = [1 + (1-p) + \sqrt(p^2 - 2p + 2)]/2.$ So, using the area formula again,

$$ r_2 = {1-p\over 2} \times {2\over [2 - p + \sqrt(p^2 - 2p + 2)]} = {1\over 2}[2 - p - \sqrt(p^2 - 2p + 2)]. $$

Similary with $ DPC $. The area of $ DPC = p/2 $ and the length $ PC = \sqrt(p^2 + 1). $ The semi perimeter of $ PC = [1 + p + \sqrt(p^2 + 1)]/2. $ So

$$ r_1 = {p\over 2} \times {2\over [1 + p + \sqrt(p^2 + 1)]} = {1\over 2}[1 + p - \sqrt(p^2 + 1)]. $$

Similarly $$ r_3 = {1\over 2} \times {2\over [1 + \sqrt(p^2 + 1) + \sqrt(p^2 -2p + 2)]} = {1\over 2}[1 + \sqrt(p^2 + 1) - \sqrt(p^2 -2p +2)][\sqrt(p^2 +1)- p]. $$

To finish this question you need to use the formulae found above which give the radii $ r_1 $, $ r_2$ and $ r_3 $ in terms of $ p $ and then consider how these values change as $ p $ varies from $0$ to $1$. For example $ r_1 $ varies from $0$ to approximately $0.293$ as $ p $ increases from $0$ to $1$.

In order to discover whether the ratio of the radii $ r_1 : r_2 : r_3 $ can ever take the value $1 : 2 : 3$ you could look at the above graphs of $ r_1 $, $ r_2 $ and $ r_3 $ as $ p $ varies from $0$ to $1$.

$r_2$ must be twice the value of $r_1$ and by inspection you can see that the only place where this is possible is when $p$ is between $0.2$ and $0.3$. We also need $r_3$ to be $3/2$ times the value of $r_2$, but this is not the case when $p$ is between $0.2$ and $0.3$. Therefore the ratio $1:2:3$ can never occur.

You may also like

Baby Circle

A small circle fits between two touching circles so that all three circles touch each other and have a common tangent? What is the exact radius of the smallest circle?

Circles Ad Infinitum

A circle is inscribed in an equilateral triangle. Smaller circles touch it and the sides of the triangle, the process continuing indefinitely. What is the sum of the areas of all the circles?

Kissing

Two perpendicular lines are tangential to two identical circles that touch. What is the largest circle that can be placed in between the two lines and the two circles and how would you construct it?