Skip over navigation

Many good solutions to this problem were sent in. The best ones came from Alex from Stoke on Trent Sixth Form College, Katie from Firhill High School Edinburgh, Andrew from St Aidan's RC School, Sunderland, David from Queen Elizabeth High, and Tom from Devonport Boys School. Andrew and Katie's reasoning relate to a tree diagram. Tom's solution appears below.

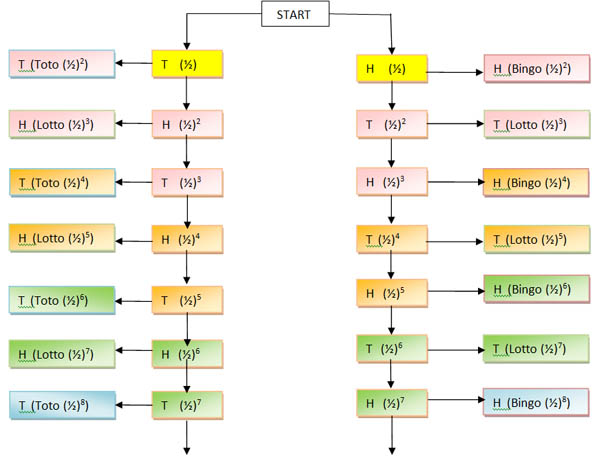

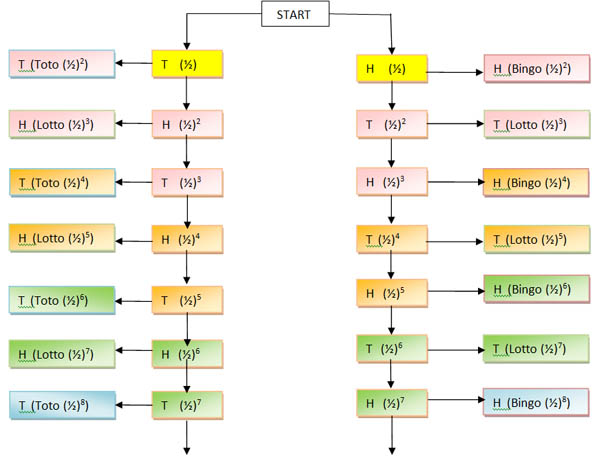

At a glance the statement seems illogical. Many people think at first that the process is unfair. Often people do not understand that by doing a coin tossing experiment to see how many trials result in each brother being chosen they only get an experimental probability that may be very different to the actual probability. The tree diagram (which may be extended indefinitely) shows the actual probabilitites. It is easy to demonstrate the fairness of this process as a way of choosing between three options.

In the tree diagram, the boxes on the right and left show a final decision. The coin tossing can go on indefinitely if no two successive heads or tails occur as shown by the vertical lines in the diagram.

Each set of 8 boxes with the same colour denotes a round of two tosses but we do not start Round 1 from the first toss (yellow) as no decision can be made until the second toss.

Note that the first throw in each round is an 'even' throw, the second an 'odd' throw.

Consider Round 1 (pink), the second and third tosses. Note that a third toss may not be necessary if the new king is chosen at the second toss. Each brother has a total probability of $0.25$ of being chosen and the probability of there being no result and going on to the next round is $0.125+0.125 = 0.25$.

So in any round: when the previous round ended on a head the next few throws could be:

(H)H,H --> Bingo (the final H is irrelevant, bingo has already won)

(H)H,T --> Bingo

(H)T,H --> No result

(H)T,T --> Lotto

When the previous round ended on a tail the possibilities are:

(T)H,H --> Lotto

(T)H,T --> No result

(T)T,H --> Toto

(T)T,T --> Toto

Consider Round 2 (orange), the fourth and fifth tosses. Note that a fifth toss may not be necessary if the new king is chosen at the fourth toss. Now from rounds 1 and 2 together, each brother has a total probability of $(0.25+(0.25)^2=5/16 $ of being chosen and the probability of there being no result and going on to the next round is $2(1/32)=1/16 =1 - 15/16$.

Tom's spreadsheet shows the calculations correct to 8 decimal places for 31 tosses, (15 rounds). We can see that, earlier on, the chances of each brother being chosen are nearly the same and we can also see that the probability of alternate heads and tails and no result being decided gets closer and closer to zero and the probabilities for each brother being chosen get closer to one third.

To find the total probability for Bingo being chosen we need to sum the following infinite geometric series (and the same series applies to the probability of Toto being chosen).

Probability of Bingo being chosen =$\frac{1}{4}+(\frac{1}{4})^2+(\frac{1}{4})^3+(\frac{1}{4})^4 \cdots = \frac{\frac{1}{4}}{1 - \frac{1}{4}}= \frac{1}{3}$.

As the probability of the process going on for ever with no decision is $\lim_{n\to\infty}(\frac{1}{4})^n = 0$ it follows that each brother has a probability of one third of being chosen.

Or search by topic

Number and algebra

Geometry and measure

Probability and statistics

Working mathematically

Advanced mathematics

For younger learners

Succession in Randomia

Age 16 to 18

Challenge Level

- Problem

- Getting Started

- Student Solutions

- Teachers' Resources

Many good solutions to this problem were sent in. The best ones came from Alex from Stoke on Trent Sixth Form College, Katie from Firhill High School Edinburgh, Andrew from St Aidan's RC School, Sunderland, David from Queen Elizabeth High, and Tom from Devonport Boys School. Andrew and Katie's reasoning relate to a tree diagram. Tom's solution appears below.

At a glance the statement seems illogical. Many people think at first that the process is unfair. Often people do not understand that by doing a coin tossing experiment to see how many trials result in each brother being chosen they only get an experimental probability that may be very different to the actual probability. The tree diagram (which may be extended indefinitely) shows the actual probabilitites. It is easy to demonstrate the fairness of this process as a way of choosing between three options.

In the tree diagram, the boxes on the right and left show a final decision. The coin tossing can go on indefinitely if no two successive heads or tails occur as shown by the vertical lines in the diagram.

Each set of 8 boxes with the same colour denotes a round of two tosses but we do not start Round 1 from the first toss (yellow) as no decision can be made until the second toss.

Note that the first throw in each round is an 'even' throw, the second an 'odd' throw.

Consider Round 1 (pink), the second and third tosses. Note that a third toss may not be necessary if the new king is chosen at the second toss. Each brother has a total probability of $0.25$ of being chosen and the probability of there being no result and going on to the next round is $0.125+0.125 = 0.25$.

So in any round: when the previous round ended on a head the next few throws could be:

(H)H,H --> Bingo (the final H is irrelevant, bingo has already won)

(H)H,T --> Bingo

(H)T,H --> No result

(H)T,T --> Lotto

When the previous round ended on a tail the possibilities are:

(T)H,H --> Lotto

(T)H,T --> No result

(T)T,H --> Toto

(T)T,T --> Toto

Consider Round 2 (orange), the fourth and fifth tosses. Note that a fifth toss may not be necessary if the new king is chosen at the fourth toss. Now from rounds 1 and 2 together, each brother has a total probability of $(0.25+(0.25)^2=5/16 $ of being chosen and the probability of there being no result and going on to the next round is $2(1/32)=1/16 =1 - 15/16$.

Tom's spreadsheet shows the calculations correct to 8 decimal places for 31 tosses, (15 rounds). We can see that, earlier on, the chances of each brother being chosen are nearly the same and we can also see that the probability of alternate heads and tails and no result being decided gets closer and closer to zero and the probabilities for each brother being chosen get closer to one third.

To find the total probability for Bingo being chosen we need to sum the following infinite geometric series (and the same series applies to the probability of Toto being chosen).

Probability of Bingo being chosen =$\frac{1}{4}+(\frac{1}{4})^2+(\frac{1}{4})^3+(\frac{1}{4})^4 \cdots = \frac{\frac{1}{4}}{1 - \frac{1}{4}}= \frac{1}{3}$.

As the probability of the process going on for ever with no decision is $\lim_{n\to\infty}(\frac{1}{4})^n = 0$ it follows that each brother has a probability of one third of being chosen.

You may also like

Rain or Shine

Predict future weather using the probability that tomorrow is wet given today is wet and the probability that tomorrow is wet given that today is dry.

Squash

If the score is 8-8 do I have more chance of winning if the winner is the first to reach 9 points or the first to reach 10 points?

Playing Squash

Playing squash involves lots of mathematics. This article explores the mathematics of a squash match and how a knowledge of probability could influence the choices you make.