Skip over navigation

You can read more about the solution to this problem on the Plus website.

Mark Yao from the British School of Manila correctly reasoned his way through this problem using tree diagrams and conditional probability; his results were similar to that obtained using the systematic enumeration shown below.

A systematic enumeration of the 64 possible continuations really helps with this problem. A key aspect is that of all possible continuations, each is equally likely.

First part

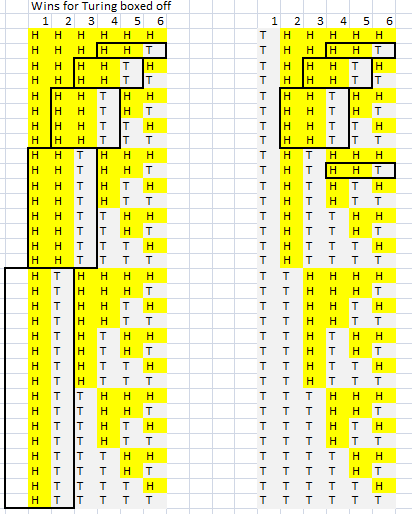

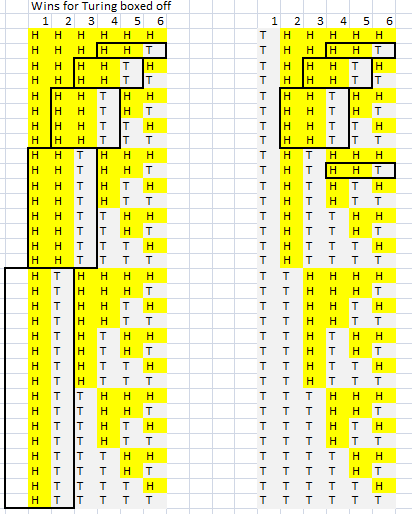

Note that Turing CANNOT lose if a Head emerges next (This would be the same if the game continued indefinitely) and will win 31 out of 32 times if a Head emerges first; a draw will occur if six Heads emerge. Moreover, Turing will win on at least two occasions if Tails emerges first. So, Turing is more likely to win than me. The following image will help you to see this:

Mark computed the probabilities as P(HTT wins) = 21/64; P(HHT wins) = 39/64.

Second part

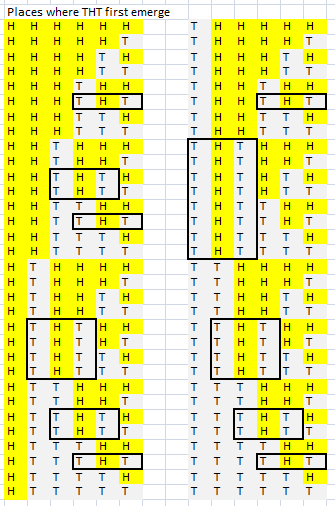

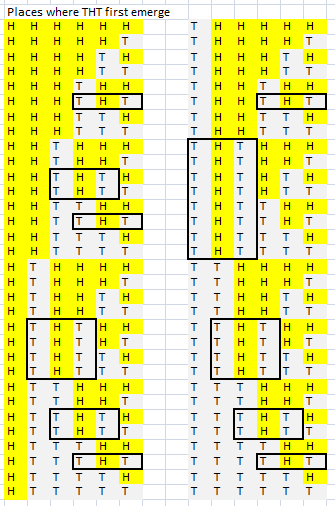

We need to beat THT to a win, so it makes sense to see when THT would occur. Using the systematic enumeration from the previous question we can see that THT emerges first in the following places

It is quite easy to see that HHT will win over THT from this list; exact probabilities could be computed by counting.

Third part

Suppose that I choose TTT. Then, consider the first time TT has emerged. Neither Turing nor I will have won prior to this point, and the game will certainly be over after the next square. We will each win with 50% probability.

Suppose I do not choose TTT. If Turing chooses TTH then he will win for certain if the first two squares are TT. There is nothing I can do about this! Suppose therefore that a H emerges before TT. Turing will need TT to start his sequence; so if my sequence is (H)(TT) then my sequence will end at the same time Turing's starts. Thus, I am guaranteed a win if a H emerges before TT. Since the chance of TT on the first two turns is exactly 1 in 4, I can guarantee a win by choosing HTT 3/4 of the time.

Lewis from The Greneway School sent in these thoughts on the infinite parts of the problem, along with a version that can be played with cards:

A HTT and HHT is in favour of the second player with odds of 2 to 1. Although, this is one of the four strongest first player choices, the odds still go in the 2nd player's favour. The weakest hand for player 1 to choose would be HHH or TTT. Player 2 needs to put the opposite letter in the first position (THH or HTT) to have 7 to 1 odds of winning. A variation of this game can be played with playing cards. Interestingly, if Player 1 chooses BBB and Player 2 chooses RBB (using the "other letter" rule mentioned above), there are odds of 99.49% of a win for Player 2, just 0.11% for Player 1 and 0.40% for a draw. The best odds player 1 can get on the cards variation is 11.61% or 1.99 to 1 in favour of Player 2. Player 2's process is to move the first 2 of Player 1's selection to the very right and add the opposite letter of the 2nd of the 2 moved to the left. The main weakness of choosing HHH is if tails is tossed once, Player 1 cannot win. This explains why the odds are stacked in favour of Player 2

Or search by topic

Number and algebra

Geometry and measure

Probability and statistics

Working mathematically

Advanced mathematics

For younger learners

Ante Up

Age 16 to 18

Challenge Level

- Problem

- Getting Started

- Student Solutions

- Teachers' Resources

You can read more about the solution to this problem on the Plus website.

Mark Yao from the British School of Manila correctly reasoned his way through this problem using tree diagrams and conditional probability; his results were similar to that obtained using the systematic enumeration shown below.

A systematic enumeration of the 64 possible continuations really helps with this problem. A key aspect is that of all possible continuations, each is equally likely.

First part

Note that Turing CANNOT lose if a Head emerges next (This would be the same if the game continued indefinitely) and will win 31 out of 32 times if a Head emerges first; a draw will occur if six Heads emerge. Moreover, Turing will win on at least two occasions if Tails emerges first. So, Turing is more likely to win than me. The following image will help you to see this:

Mark computed the probabilities as P(HTT wins) = 21/64; P(HHT wins) = 39/64.

Second part

We need to beat THT to a win, so it makes sense to see when THT would occur. Using the systematic enumeration from the previous question we can see that THT emerges first in the following places

It is quite easy to see that HHT will win over THT from this list; exact probabilities could be computed by counting.

Third part

Suppose that I choose TTT. Then, consider the first time TT has emerged. Neither Turing nor I will have won prior to this point, and the game will certainly be over after the next square. We will each win with 50% probability.

Suppose I do not choose TTT. If Turing chooses TTH then he will win for certain if the first two squares are TT. There is nothing I can do about this! Suppose therefore that a H emerges before TT. Turing will need TT to start his sequence; so if my sequence is (H)(TT) then my sequence will end at the same time Turing's starts. Thus, I am guaranteed a win if a H emerges before TT. Since the chance of TT on the first two turns is exactly 1 in 4, I can guarantee a win by choosing HTT 3/4 of the time.

Lewis from The Greneway School sent in these thoughts on the infinite parts of the problem, along with a version that can be played with cards:

A HTT and HHT is in favour of the second player with odds of 2 to 1. Although, this is one of the four strongest first player choices, the odds still go in the 2nd player's favour. The weakest hand for player 1 to choose would be HHH or TTT. Player 2 needs to put the opposite letter in the first position (THH or HTT) to have 7 to 1 odds of winning. A variation of this game can be played with playing cards. Interestingly, if Player 1 chooses BBB and Player 2 chooses RBB (using the "other letter" rule mentioned above), there are odds of 99.49% of a win for Player 2, just 0.11% for Player 1 and 0.40% for a draw. The best odds player 1 can get on the cards variation is 11.61% or 1.99 to 1 in favour of Player 2. Player 2's process is to move the first 2 of Player 1's selection to the very right and add the opposite letter of the 2nd of the 2 moved to the left. The main weakness of choosing HHH is if tails is tossed once, Player 1 cannot win. This explains why the odds are stacked in favour of Player 2

You may also like

Rain or Shine

Predict future weather using the probability that tomorrow is wet given today is wet and the probability that tomorrow is wet given that today is dry.

Squash

If the score is 8-8 do I have more chance of winning if the winner is the first to reach 9 points or the first to reach 10 points?

Playing Squash

Playing squash involves lots of mathematics. This article explores the mathematics of a squash match and how a knowledge of probability could influence the choices you make.