Skip over navigation

Jack and Ashley from Sir Harry Smith Community College sent us the following thoughts:

$(1+2+3+...+n)^2$ is equal to $1^3+2^3+3^3+...+n^3$, which can also be written $$\left(\sum_{r=1}^n r \right)^2 = \sum_{r=1}^n r^3$$

We tested this formula with two examples:

$1^3+2^3+...+6^3=441$, and $1+2+...+6=21, 21^2=441$.

$1^3+2^3+...+10^3=3025$, and $1+2+...+10=55, 55^2=3025$.

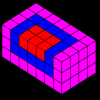

An anonymous solver from Mearns Castle School explained very clearly how the diagram shows the two parts of the formula:

The area of the square can be looked at in different ways.

The columns are $1$ then $2$ then $3$ then $4$ units long. It is a square, so the area is the length squared which is $(1+2+3+4+5+6)^2$.

Now look at each of the 6 backward L shapes.

We have the indicated square on the diagonal (for example, on the blue L shape $5^2$), then we have other congruent squares (shaded in the same colour).

Note that in even levels, there are two half-squares which make up one full square. So the area of the blue shaded level is: $5^2+4\times5^2 = (5^2)(1+4) =(5^2)(5) =5^3$

As this is true for the first, second, third... $n^{th}$ level of the area of the $n^{th}$ level is $n^3$.

This means if there are $n$ levels, the length of one side of the square is $1+2+3...+(n-1)+n$ and thus the area equals $(1+2+3...+(n-1)+n)^2$.

But considering the area in terms of each level gives $(1^3)+(2^3)+(3^3)...+(n-1)^3+(n^3)$.

So it can be said $(1^3)+(2^3)+(3^3)...+(n-1)^3+(n^3) = (1+2+3...+(n-1)+n)^2$.

John from Takapuna Grammar School used induction to prove the formula:

Using induction we should first prove that $1^3$ is equal to $1^2$, which is obvious, as they're both equal to $1$.

Now to prove that any added number $(n+1)$ would keep the equation satisfied:

The formula for any triangular number $(1 + 2 + 3...+ n)$ is $\frac{n(n+1)}{2}$.

Now we observe the way in which new tiles are put on. There are $(n+1)$ squares to be added, which contain $(n+1)^2$ units each, making $(n+1)^3$.

One of these squares is placed diagonally to the original square and the other $n$ squares are placed along the sides.

Since there are two sides to place against, this means that there are $\frac{n}{2}$ squares per side, and because each square is $(n+1)$ units long that means there are $\frac{n(n+1)}{2}$ units covered on each side.

There are $\frac{n(n+1)}{2}$ units on each side of the original square so that means all of the units on each side are covered, leaving the last $(n+1)^2$ square (the one that is diagonal to the original square) to make a new square itself.

Finally, we know that each side of this new square is the $(n+1)^{th}$ triangular number, because the previous square's length was the $n^{th}$ triangular number, and this length has increased by (n+1).

Therefore the equation $(1^3 + 2^3...n^3)=(1 + 2... + n)^2$ holds for all positive whole numbers, because it is true for n=1 and if it's true for any number n then it's true for n + 1.

Or search by topic

Number and algebra

Geometry and measure

Probability and statistics

Working mathematically

Advanced mathematics

For younger learners

Picture Story

Age 14 to 16

Challenge Level

- Problem

- Getting Started

- Student Solutions

- Teachers' Resources

Jack and Ashley from Sir Harry Smith Community College sent us the following thoughts:

$(1+2+3+...+n)^2$ is equal to $1^3+2^3+3^3+...+n^3$, which can also be written $$\left(\sum_{r=1}^n r \right)^2 = \sum_{r=1}^n r^3$$

We tested this formula with two examples:

$1^3+2^3+...+6^3=441$, and $1+2+...+6=21, 21^2=441$.

$1^3+2^3+...+10^3=3025$, and $1+2+...+10=55, 55^2=3025$.

An anonymous solver from Mearns Castle School explained very clearly how the diagram shows the two parts of the formula:

The area of the square can be looked at in different ways.

The columns are $1$ then $2$ then $3$ then $4$ units long. It is a square, so the area is the length squared which is $(1+2+3+4+5+6)^2$.

Now look at each of the 6 backward L shapes.

We have the indicated square on the diagonal (for example, on the blue L shape $5^2$), then we have other congruent squares (shaded in the same colour).

Note that in even levels, there are two half-squares which make up one full square. So the area of the blue shaded level is: $5^2+4\times5^2 = (5^2)(1+4) =(5^2)(5) =5^3$

As this is true for the first, second, third... $n^{th}$ level of the area of the $n^{th}$ level is $n^3$.

This means if there are $n$ levels, the length of one side of the square is $1+2+3...+(n-1)+n$ and thus the area equals $(1+2+3...+(n-1)+n)^2$.

But considering the area in terms of each level gives $(1^3)+(2^3)+(3^3)...+(n-1)^3+(n^3)$.

So it can be said $(1^3)+(2^3)+(3^3)...+(n-1)^3+(n^3) = (1+2+3...+(n-1)+n)^2$.

John from Takapuna Grammar School used induction to prove the formula:

Using induction we should first prove that $1^3$ is equal to $1^2$, which is obvious, as they're both equal to $1$.

Now to prove that any added number $(n+1)$ would keep the equation satisfied:

The formula for any triangular number $(1 + 2 + 3...+ n)$ is $\frac{n(n+1)}{2}$.

Now we observe the way in which new tiles are put on. There are $(n+1)$ squares to be added, which contain $(n+1)^2$ units each, making $(n+1)^3$.

One of these squares is placed diagonally to the original square and the other $n$ squares are placed along the sides.

Since there are two sides to place against, this means that there are $\frac{n}{2}$ squares per side, and because each square is $(n+1)$ units long that means there are $\frac{n(n+1)}{2}$ units covered on each side.

There are $\frac{n(n+1)}{2}$ units on each side of the original square so that means all of the units on each side are covered, leaving the last $(n+1)^2$ square (the one that is diagonal to the original square) to make a new square itself.

Finally, we know that each side of this new square is the $(n+1)^{th}$ triangular number, because the previous square's length was the $n^{th}$ triangular number, and this length has increased by (n+1).

Therefore the equation $(1^3 + 2^3...n^3)=(1 + 2... + n)^2$ holds for all positive whole numbers, because it is true for n=1 and if it's true for any number n then it's true for n + 1.

You may also like

Sums of Powers - A Festive Story

A story for students about adding powers of integers - with a festive twist.

Summing Squares

Discover a way to sum square numbers by building cuboids from small cubes. Can you picture how the sequence will grow?