Skip over navigation

This tough nut was cracked by Benjamin Girard, age 18, from Lycee Pierre Bourdan in Gueret, France, Jonathan Bartlett, age 17, Brockenhurst College, Hampshire, Annamalai Meena, age 18, VVCE, Mysore, Karnataka, India, M Ali Khan, age 17 from Horley, Surrey and Andaleeb Ahmed, age 17, from Woodhouse Sixth Form College, London using interestingly different methods. Jonathan, Annamalai and Andaleeb used algebra based on Pythagoras' Theorem while Benjamin and Ali used trigonometry. We give both methods because they show important connections between different mathematical concepts.

First Jonathan, Annamalai and Andaleeb's method. Their solutions were very well explained and very clear, well done! Jonathan's work is reproduced here as it arrived first.

Part 1: The distances between the parallel lines are $a=1$ unit and $b=2$ units. Let $x$ denote the length of the sides of the equilateral triangle. Labelled Diagram Form three right angled triangles between each side of the equilateral triangle and the parallel lines to gain the following three equations based on Pythagoras Theorem:

Part 2: The distances between the parallel lines are $a$ and $b$. \par Following an almost identical process to Part 1:

Comment: The algebraic method gives the exact answer. Mathematical methods for constructing diagrams using only a ruler and compasses depend on it being possible to calculate lengths using only the four arithmetic operations, exponents and square roots.

Benjamin's method is elegant and also very well explained. It uses trigonometry involving more advanced techniques and 'heavier mathematical machinery' to crack the problem and gives the length $x$ in terms of an inverse tangent function." Labelled Diagram We have $\cos \alpha = {a \over x}$ and $\cos \beta = {b \over x}$. So $$ {\cos \alpha \over \cos \beta} = {a \over b}$$ with $\alpha +\beta = {2\pi \over 3}$. \par From this, for any given values of $a$ and $b$, we can find $\beta$ and the value of $x$. We use $\cos {2\pi \over 3} = -{1 \over 2}$ and $\sin {2\pi \over 3} = {\sqrt3 \over 2}$.

So we have $\beta$, therefore we have $\cos \beta$ and as we know $b$ we know $x$.

This result, with $a = 1$ and $b = 2$, gives us $x = 3.055...$.

Or search by topic

Number and algebra

Geometry and measure

Probability and statistics

Working mathematically

Advanced mathematics

For younger learners

Pareq Calc

Age 14 to 16

Challenge Level

- Problem

- Student Solutions

This tough nut was cracked by Benjamin Girard, age 18, from Lycee Pierre Bourdan in Gueret, France, Jonathan Bartlett, age 17, Brockenhurst College, Hampshire, Annamalai Meena, age 18, VVCE, Mysore, Karnataka, India, M Ali Khan, age 17 from Horley, Surrey and Andaleeb Ahmed, age 17, from Woodhouse Sixth Form College, London using interestingly different methods. Jonathan, Annamalai and Andaleeb used algebra based on Pythagoras' Theorem while Benjamin and Ali used trigonometry. We give both methods because they show important connections between different mathematical concepts.

First Jonathan, Annamalai and Andaleeb's method. Their solutions were very well explained and very clear, well done! Jonathan's work is reproduced here as it arrived first.

Part 1: The distances between the parallel lines are $a=1$ unit and $b=2$ units. Let $x$ denote the length of the sides of the equilateral triangle. Labelled Diagram Form three right angled triangles between each side of the equilateral triangle and the parallel lines to gain the following three equations based on Pythagoras Theorem:

\begin{eqnarray} 2^2 + c^2 &=& x^2\quad

&(1) \\ 3^2 + d^2 &=& x^2\quad &(2) \\ 1^2 +

(c+d)^2 &=& x^2.\quad &(3) \end{eqnarray}

Rearrange the first two equations and expand and rearrange the

third:

\begin{eqnarray} c^2 &=& x^2 - 4\quad

&(1) \\ d^2 &=& x^2 - 9\quad &(2) \\ 2cd

&=& x^2 -1 -c^2 - d^2.\quad &(3) \end{eqnarray}

Rearrange the first two equations and expand and rearrange the

third: Substitute (1) and (2) into (3) and simplify: $$ 2cd = 12 -

x^2. $$ Now square both sides: $$ 4c^2d^2 = 144 - 24x^2 + x^4.$$

Substitute (1) and (2) into the left hand side: $$ 4(x^2 - 4)(x^2 -

9)= 144 - 24x^2 + x^4.$$ Multiply out the brackets, simplify and

tidy up: $$ 4x^4 - 52x^2 + 144 = 144 - 24x^2 + x^4$$ $$ 3x^4 =

28x^2$$ $$ x = \sqrt {28/3} = 3.055 \ {\rm (3\ decimal\ places)}.$$

Part 2: The distances between the parallel lines are $a$ and $b$. \par Following an almost identical process to Part 1:

\begin{eqnarray} c^2 &=& x^2 - b^2 \quad

&(1) \\ d^2 &=& x^2 - (a + b)^2 \quad &(2) \\ x^2

&=& a^2 + (c + d)^2. \quad &(3) \end{eqnarray}

Expand and rearrange (3) and substitute (1) and (2) into (3):

\begin{eqnarray} 2cd &=& x^2 - a^2 -c^2 -

d^2 \\ &=& x^2 - a^2 - x^2 + b^2 - x^2 + a^2 + 2ab + b^2 \\

&=& 2b^2 + 2ab - x^2. \end{eqnarray}

As before, using only elementary algebra, you can obtain an

expression giving $x^2$ in terms of $a$ and $b$ by eliminating $c$

and $d$. Square both sides, substitute for $c^2$ and $d^2$ on the

left hand side, expand, collect like terms and simplify. This

gives: $$ 3x^4 = 4x^2(a^2 + ab + b^2)$$ and hence the length of the

side of the equilateral triangle is given by: $$ x = \sqrt {4(a^2 +

ab + b^2)/3}.$$ Comment: The algebraic method gives the exact answer. Mathematical methods for constructing diagrams using only a ruler and compasses depend on it being possible to calculate lengths using only the four arithmetic operations, exponents and square roots.

Benjamin's method is elegant and also very well explained. It uses trigonometry involving more advanced techniques and 'heavier mathematical machinery' to crack the problem and gives the length $x$ in terms of an inverse tangent function." Labelled Diagram We have $\cos \alpha = {a \over x}$ and $\cos \beta = {b \over x}$. So $$ {\cos \alpha \over \cos \beta} = {a \over b}$$ with $\alpha +\beta = {2\pi \over 3}$. \par From this, for any given values of $a$ and $b$, we can find $\beta$ and the value of $x$. We use $\cos {2\pi \over 3} = -{1 \over 2}$ and $\sin {2\pi \over 3} = {\sqrt3 \over 2}$.

\begin{eqnarray} & {\cos (2\pi /3 - \beta)

\over \cos \beta} = {a \over b}\\ \Longleftrightarrow & {{\cos

2\pi /3 \cos \beta + \sin 2\pi /3 \sin \beta}\over \cos \beta} = {a

\over b} \\ \Longleftrightarrow & \cos 2\pi /3 + \sin 2\pi /3

\tan \beta = {a \over b} \\ \Longleftrightarrow & \tan \beta =

{{2a + b} \over b\sqrt 3} \end{eqnarray}

So we have $\beta$, therefore we have $\cos \beta$ and as we know $b$ we know $x$.

This result, with $a = 1$ and $b = 2$, gives us $x = 3.055...$.

You may also like

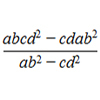

DOTS Division

Take any pair of two digit numbers x=ab and y=cd where, without loss of generality, ab > cd . Form two 4 digit numbers r=abcd and s=cdab and calculate: {r^2 - s^2} /{x^2 - y^2}.

Sixational

The nth term of a sequence is given by the formula n^3 + 11n. Find the first four terms of the sequence given by this formula and the first term of the sequence which is bigger than one million. Prove that all terms of the sequence are divisible by 6.