Or search by topic

Number and algebra

Geometry and measure

Probability and statistics

Working mathematically

Advanced mathematics

For younger learners

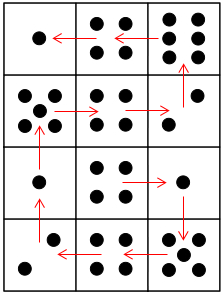

Rolling That Cube

- Problem

- Getting Started

- Student Solutions

- Teachers' Resources

This activity produced a few replies. Oliver from St. Anthony's sent in;

R R D L L D D R R U L

Tessa, Sally and Kensa from Sherwood State School in Australia sent in their solution like this;

$1, 4, 6, 2, 4, 5, 1, 2, 4, 5, 1, 4$

Hanako and Emilia at Vale Junior School, Guernsey sent in this word document;

First we decided to make a cube to physically test our theories and ideas.

We spotted that there were two impossible routes. These were: the $4$s down the middle and the $1, 4, 1$ combination going across.

These are impossible because you can't have two $4$s next to each other as there is only one four on the dice. The other is impossible as to get from $1$ to $4$, and then to $1$ again, you would have to double back on yourself.

Next, we had to think of a route that bypassed these two impossible combinations. We thought that we could start our route with the $4$ in the impossible $1, 4, 1$ combination so that we didn't have to complete the whole impossible combination.

We checked that our theory was correct by rolling our cube along the grid. As we rolled it, we wrote the next number in the grid as a reflection on the next face of the cube. We tried starting at the top $1$ and the centre $4$ and we found that this route works both ways.

Thank you Hanaho and Emilia for explaining how you did it and what your thoughts were and well done all of you!

You may also like

Plants

Three children are going to buy some plants for their birthdays. They will plant them within circular paths. How could they do this?

Triangle Animals

How many different ways can you find to join three equilateral triangles together? Can you convince us that you have found them all?

Junior Frogs

Have a go at this well-known challenge. Can you swap the frogs and toads in as few slides and jumps as possible?