Skip over navigation

In general, if $L_n$ is the length of the spoke with $n$ spokes, $x_n$ the length of the edge of the polygon in the centre and $r_n$ the radius of the circumcircle of the polygon,then $$L_n = {x_n\over 2} + \sqrt {1 - (r_n\cos {\pi\over n})^2}$$ so that$L_n \to 1$ as $n\to \infty$.\par For $n=3$, $L_n \approx 1.595$; for $n=20$, $L_n\approx 1.011$ and for ${n=30}$, $L_n\approx 1.003$.

Or search by topic

Number and algebra

Geometry and measure

Probability and statistics

Working mathematically

Advanced mathematics

For younger learners

Spokes

Age 16 to 18

Challenge Level

- Problem

- Getting Started

- Student Solutions

- Teachers' Resources

|

You know what the area of the four parts must be.

Think about symmetrical drawings.

Can you draw three lines inside the circle in such a way that

they enclose an area which can be expanded or contracted to give

the required area?

The Solution section gives one possibility (see link above).

There are many other possibilities you could investigate.

Here is just one alternative line of approach you could

pursue:

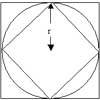

The diagram shows another solution for 3 lines but the same

principle applies to any regular polygon. For an $n$-gon the angle

marked at the centre of the circle $C$ will be ${\pi \over n}$. As

$n$ gets larger the polygons will get smaller and the lines will

'radiate' out more like the spokes of a wheel.

|

In general, if $L_n$ is the length of the spoke with $n$ spokes, $x_n$ the length of the edge of the polygon in the centre and $r_n$ the radius of the circumcircle of the polygon,then $$L_n = {x_n\over 2} + \sqrt {1 - (r_n\cos {\pi\over n})^2}$$ so that$L_n \to 1$ as $n\to \infty$.\par For $n=3$, $L_n \approx 1.595$; for $n=20$, $L_n\approx 1.011$ and for ${n=30}$, $L_n\approx 1.003$.

You may also like

Mean Geometrically

A and B are two points on a circle centre O. Tangents at A and B cut at C. CO cuts the circle at D. What is the relationship between areas of ADBO, ABO and ACBO?

Approximating Pi

By inscribing a circle in a square and then a square in a circle find an approximation to pi. By using a hexagon, can you improve on the approximation?